Cave Angel Fish

Cryptotora thamicola

The cave angel is a pale and eyeless fish endemic to a few limestone caves in northwestern Thailand. It’s the only known living fish with a pelvic girdle fused to its spine — structurally similar to early land vertebrates — giving it the ability to “walk” up waterfalls.

They say you shouldn’t judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, but who’s to say a fish couldn’t climb one.

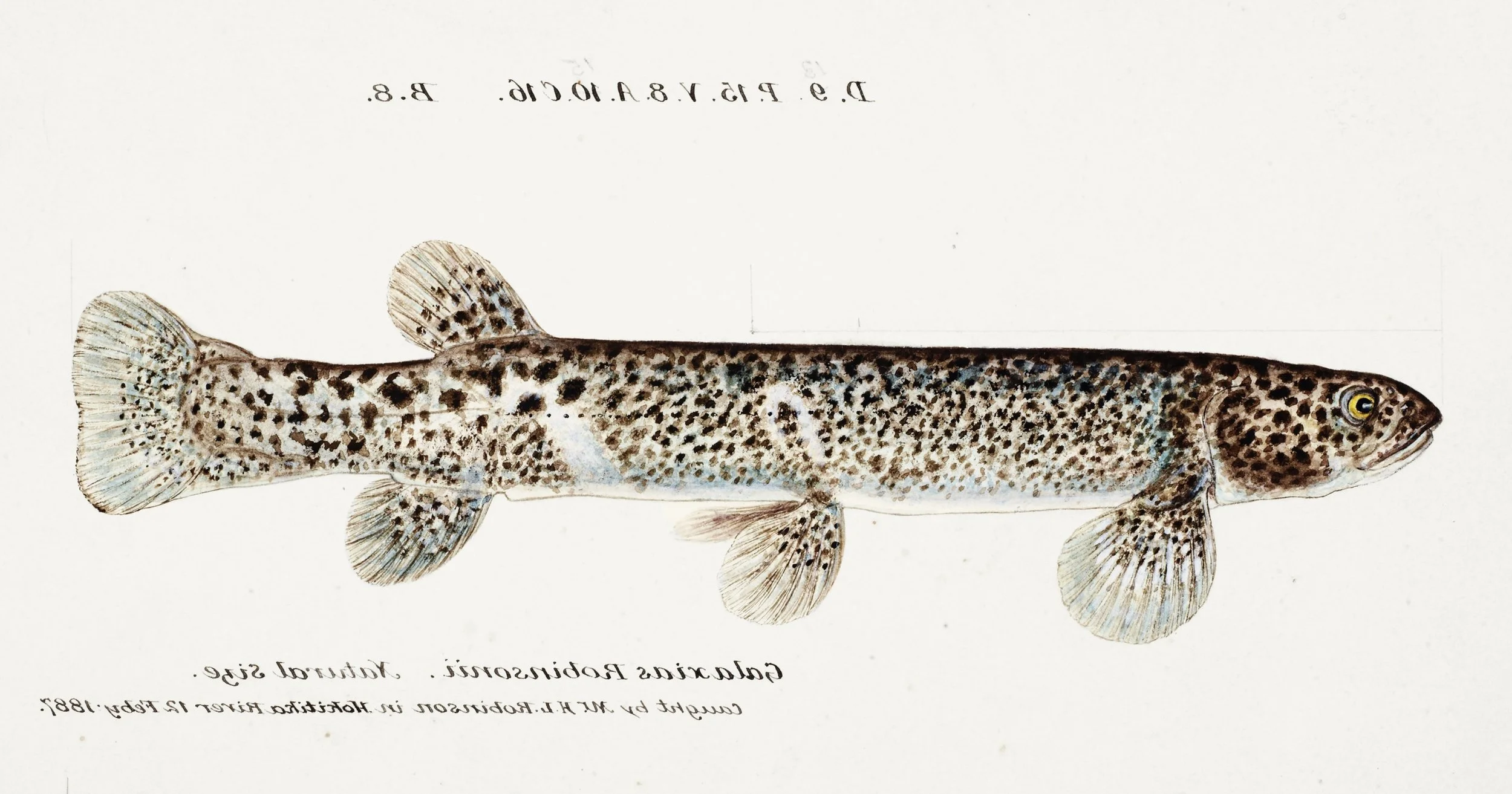

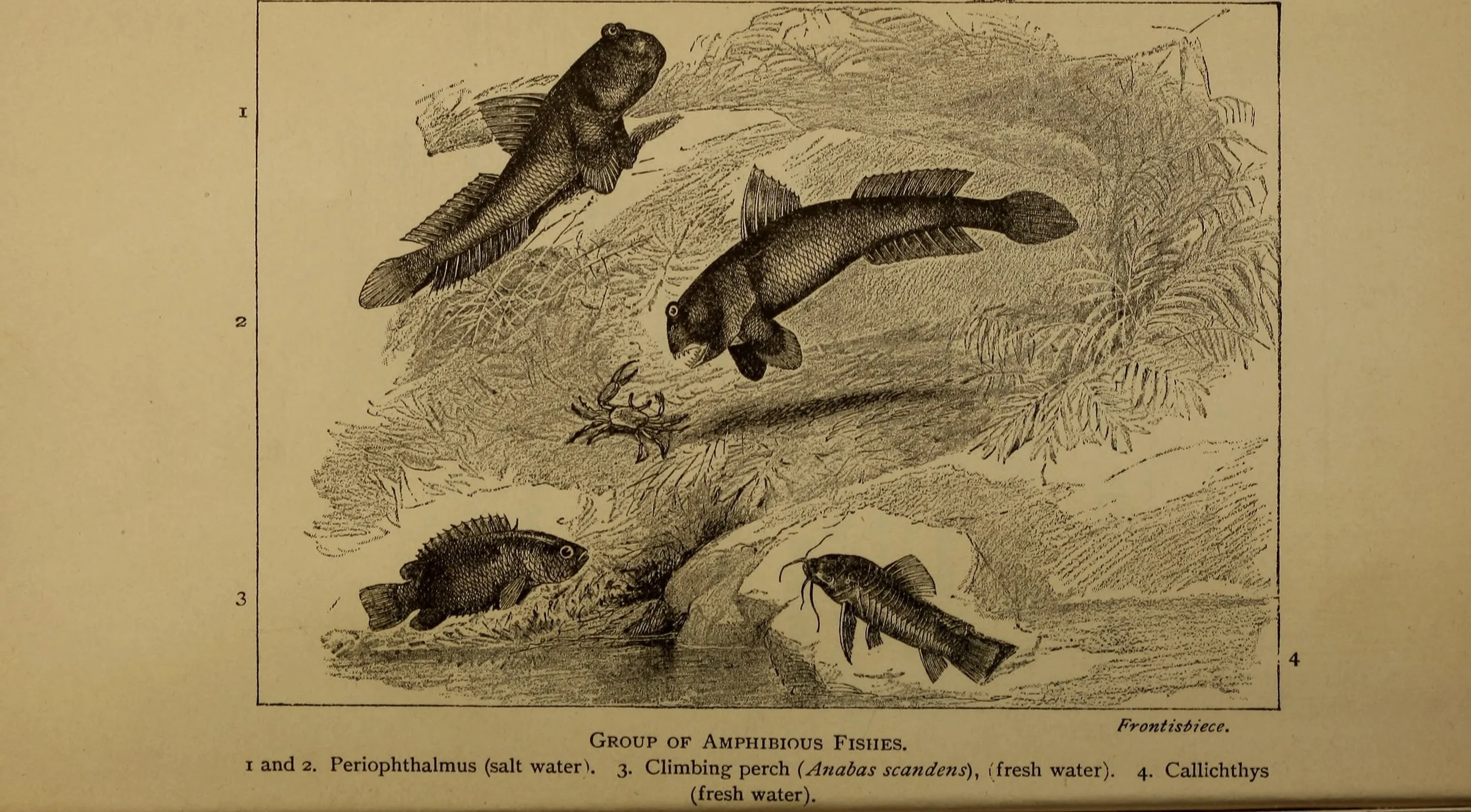

The climbing perch is a fairly ordinary-looking fish, and while it doesn’t quite climb trees, it can leave the water and clamber across dry land. The mudskipper is a fish that actually climbs trees, using its pectoral fins like arms to crawl up roots, branches, and mangrove trunks, occasionally reaching elevations above the high tide mark. Then there’s the climbing galaxias; a mountaineer of a fish with strong pectoral and pelvic fins that allow it to scale vertical rock faces tens of metres high.

Whoever coined that famous saying clearly hadn’t known of these fish.

They may be forgiven, however, for overlooking the oddest of the piscine climbers, for it wasn’t described until 1988, and, even then, the world only learned of its climbing talents in 2016. It is a ghostly, eyeless creature, from the caves of northern Thailand.

The Cave Angel

Cryptotora thamicola.

This species’ specific name comes from the Thai word for ‘cave,’ tham, and the latin for ‘to inhabit,’ colere — the fish is a true troglobite, a cave-dweller, a permanent spelunker. It was first discovered in Tham Susa, a karst cave in northern Thailand’s Mae Hong Son Province near the Myanmar border, and later found in other nearby cave systems.

Its total known range spans some 200 kilometres², but its actual inhabited range — the extent of its dark watery world, scattered across eight subterranean sites — is a mere 6 kilometres². How connected are its various populations? Is there an undiscovered labyrinth of submerged passages that these fish slither through? Maybe. We don’t yet know. Not only are their subterranean passages challenging to map, the fish themselves aren’t all that easy to find, given their size: no larger than a paperclip.

C. thamicola is a loach in the family Balitoridae: the river loaches. Most of its 200+ relatives are adapted for living in fast-flowing streams, with modified fins for clinging to rocks.

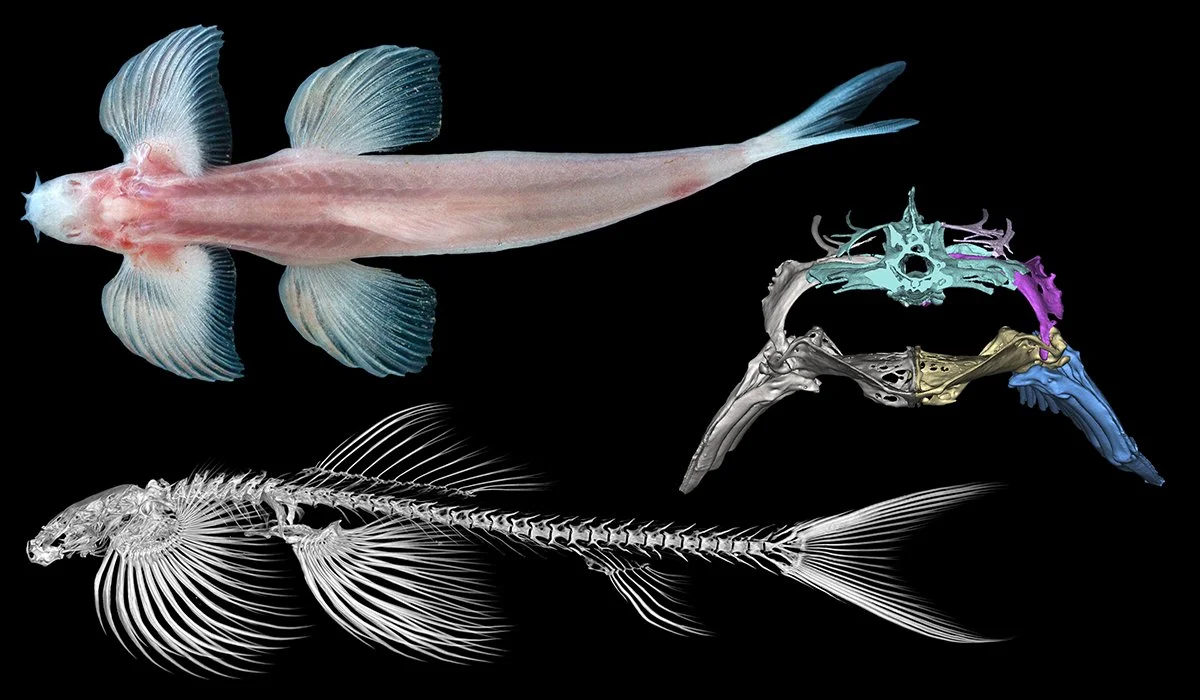

C. thamicola is more commonly known as the cave angel fish, and, although the name does fit, it resembles less a stereotypical angel and more a biblically accurate one. Its serpentine body is skinny and pale pink, with a translucent tail at one end and a rounded white head at the other. Four fins protrude from its body, two on each side, forming the impression of spectral wings. However, unlike the angels of Revelation — which “were full of eyes round about” — the cave angel has none at all.

Perhaps then, it is a fallen angel: punished, banished to the dark underworld where it lost its sight, and then lost its eyes completely. With its “wings” — its pale fins — it clings to damp cold rock, battered by cascades of water. And it climbs upwards.

Another name given to this species is the waterfall climbing cave fish.

In its karst habitat, the limestone is pockmarked with holes, chambers, and vertical passages. The eroding water doesn’t flow as a flat, smooth stream; it trickles, seeps, drops and plunges through narrow gaps and down into pits. Should a fish be caught in the current, it could easily be flung over a ledge, swept down a waterfall, and dragged to the bottom of some deep abyss where food is scarce or non-existent. It would be an advantage, in such a situation, to be a fish that can climb waterfalls.

Climbing Out of Water

Millimetre by millimetre, inch by inch, the cave angel drags itself up near-vertical walls.

The secret to this fish’s unlikely athleticism lies in its special fins and the accompanying anatomy that supports them.

Out of all known fish, approximately 35,000 species, the cave angel is the only one with a pelvic girdle fused to its vertebral column. This anatomical anomaly, which sounds like some inconsequential quirk, could actually shed light on one of the great developments in the evolution of animals: how fish first made it onto land to become amphibians, reptiles, birds, and, eventually, us.

In most fish, the pelvic girdle — the bony or cartilaginous structure that supports the pelvic fins — is a loose, floating element. It usually lies embedded in muscle, unconnected to the spine, and offers limited support. Pelvic fins in these (majority of) fish are mainly used for steering, stabilizing, or slowly maneuvering near the seafloor; they do not bear weight or generate force. But in the cave angel, whose pelvic girdle is fused directly to the vertebral column, this solid connection lets it exert force from its pelvic fins and through its body, to push against rock, and to climb up it.

“Out of all known fish, approximately 35,000 species, the cave angel is the only one with a pelvic girdle fused to its vertebral column.”

As mentioned before, this is a skeletal structure otherwise unseen in living fishes. It does, however, resemble the hip bones of terrestrial animals — which are crucial for walking on land.

Watch this fish climb or crawl across rock, its long body swiveling left and right, and it may bring to mind a salamander. Its large and muscular pelvic fins are positioned to push itself forwards, just as a salamander’s limbs — protruding from the sides of its body — enable it to walk. In fact, high-resolution scans reveal that this pelvic girdle is structurally almost identical to that of early tetrapods, supporting a walking gait remarkably similar to salamanders.

The gait of an early tetrapod is similar to that of modern day salamanders — and the cave angel fish.¹

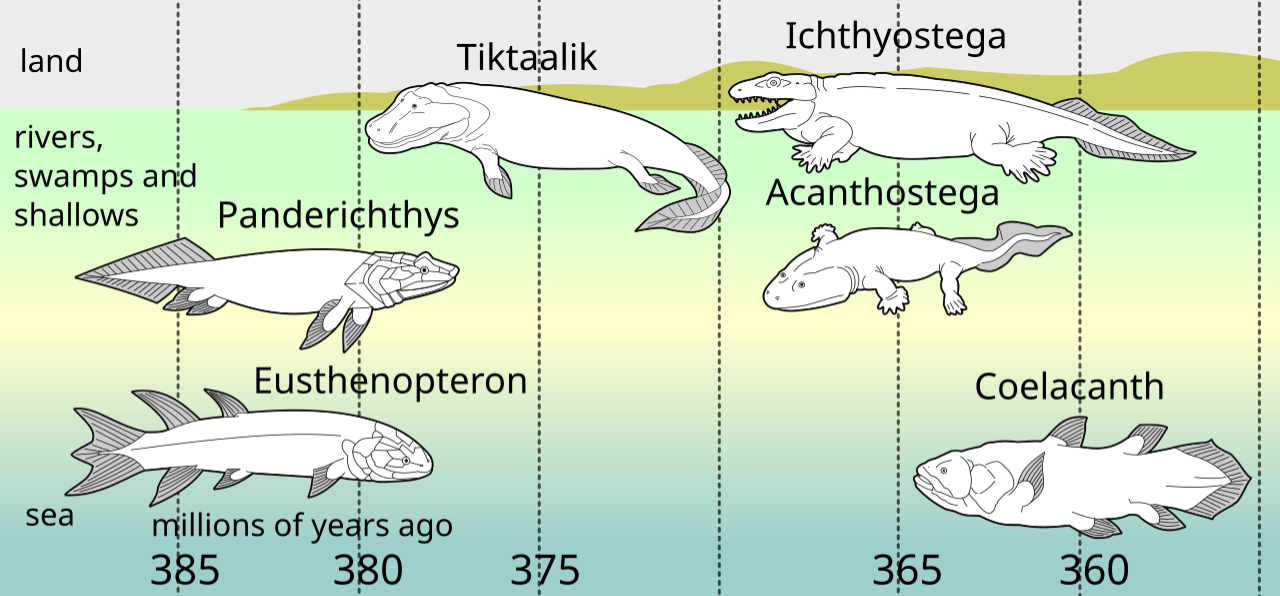

The comparison isn’t random. The first tetrapods to walk on land were thought to closely resemble salamanders in form and movement. How they got onto land, from aquatic and finned fish, is the question. To find the answer we’ve uncovered the fossils of species long dead and consulted the anatomies of those still living.

Fossils have so far yielded a plausible and illuminating record of the transition from fish to land-dwelling tetrapod. But the fossil record is notoriously incomplete¹ — even the species we arrange into a sequence probably never begot or were begotten by one another, but were instead close relatives to similar species who were the actual ancestors and descendants of a continual line (they were just never fossilised). And so we look to living species to help fill in the gaps.

Convergence

This is where the concept of convergence becomes invaluable to the study of evolution.

Evolution, or rather natural selection — the process that drives most (but not all) of the consequential changes — is practical. If something works, natural selection will keep coming back to that solution. The eye, for example, is an organ that works. It works so well, in fact, that it has evolved independently over 40 times in animals as different as spiders, squids, clams, humans, and flatworms. But natural selection is also thrifty.

To give an opposite, and more pertinent example of convergent evolution: hypogean animals (that is, those that live underground) have repeatedly and separately adapted to their lightless habitats by losing their vision and, often, their eyes altogether. Why? Well, you don’t need gills if you live on land, and you don’t need eyes when you live in a place with no light. Eyes are expensive organs to develop, and if they have no use, that energy can be invested elsewhere — not to mention that eyes are quite vulnerable to injury and infection. And so we get a blind salamander in the olm, a blind spider in the Kauai’i cave wolf, blind shrimp from caves in Kentucky and Alabama, and several blind cave fish, including one species, the Mexican tetra, with a seeing variant that lives in rivers and springs and an eyeless variant that lives in caves. And, of course, there’s the cave angel too.

That is convergent evolution.

We see it everywhere between living species.² We also see it between living species and those that we know from the fossil record. So it only makes sense to use our knowledge of convergent evolution to fill in the missing pieces of the record.

There are several fish today that can help us “recreate” the initial transition onto land.

Some have been mentioned up top, like the mudskippers, who, despite having ray-like bone arrangements in their fins and also lacking lungs, must often leap and crawl out of water. Why? What would compel a fish to take to the land?

The mudskipper lives in a highly dynamic environment; twice a day, tides flood and expose the muddy floor of the mangroves. At low tide, when the mudflats are exposed, mudskippers emerge to forage, fight, and flirt — breathing through their skin and the moist linings of their mouths and throats. During high tide, when the waters return, so do most of the predators. By leaving the water, climbing onto mangrove roots, the mudskipper can avoid much of the danger. And beyond simple safety, there’s opportunity; for instance, the mudskipper can find food on land that other fish can’t reach.

Other fish amble onto land because their current aquatic home is no longer habitable, whether they’re fleeing foul conditions like extreme temperatures, salinity shifts, or drought, or simply seeking more plentiful pools. The walking catfish leaves its stagnant pond or ditch, and "walks” — more like wiggles and flops, sometimes using its pectoral fins like a mudskipper — across dry land to find a more fitting home. Some fish, like the Pacific leaping blenny, even lay their eggs outside of water, hiding them in limestone crevices or damp nooks where the tides can't wash them away.

So that’s the why of it: our pioneering tetrapod ancestors may have been pushed toward a more land-lubbing existence by any, or several of the above reasons. But what about the how? How does a fish survive out of water?

Living Fossils

While the mudskipper exchanges gases through its skin and the walking catfish breathes using a specialised organ located above its gills, neither possesses anything resembling true lungs. Those organs first appeared in early bony fish, likely as an adaptation to anoxic waters, allowing them to gulp air at the surface and get extra oxygen.

Today, six living species of lungfish still possess true lungs and one of them, the Australian lungfish, still uses them in precisely this way: relying on its gills when oxygen in the water is plentiful, and on its lungs when it’s not.³ This is a kind of mixed strategy; a bridge, you could say, between gilled fish and lunged tetrapods. The other five species of lungfish are even more air dependent. Even when the water is well-oxygenated, they must still surface to breathe air as their gills alone are usually insufficient for the task.

But it's not enough to just breathe. Our ancestors needed to be able to move across land too.

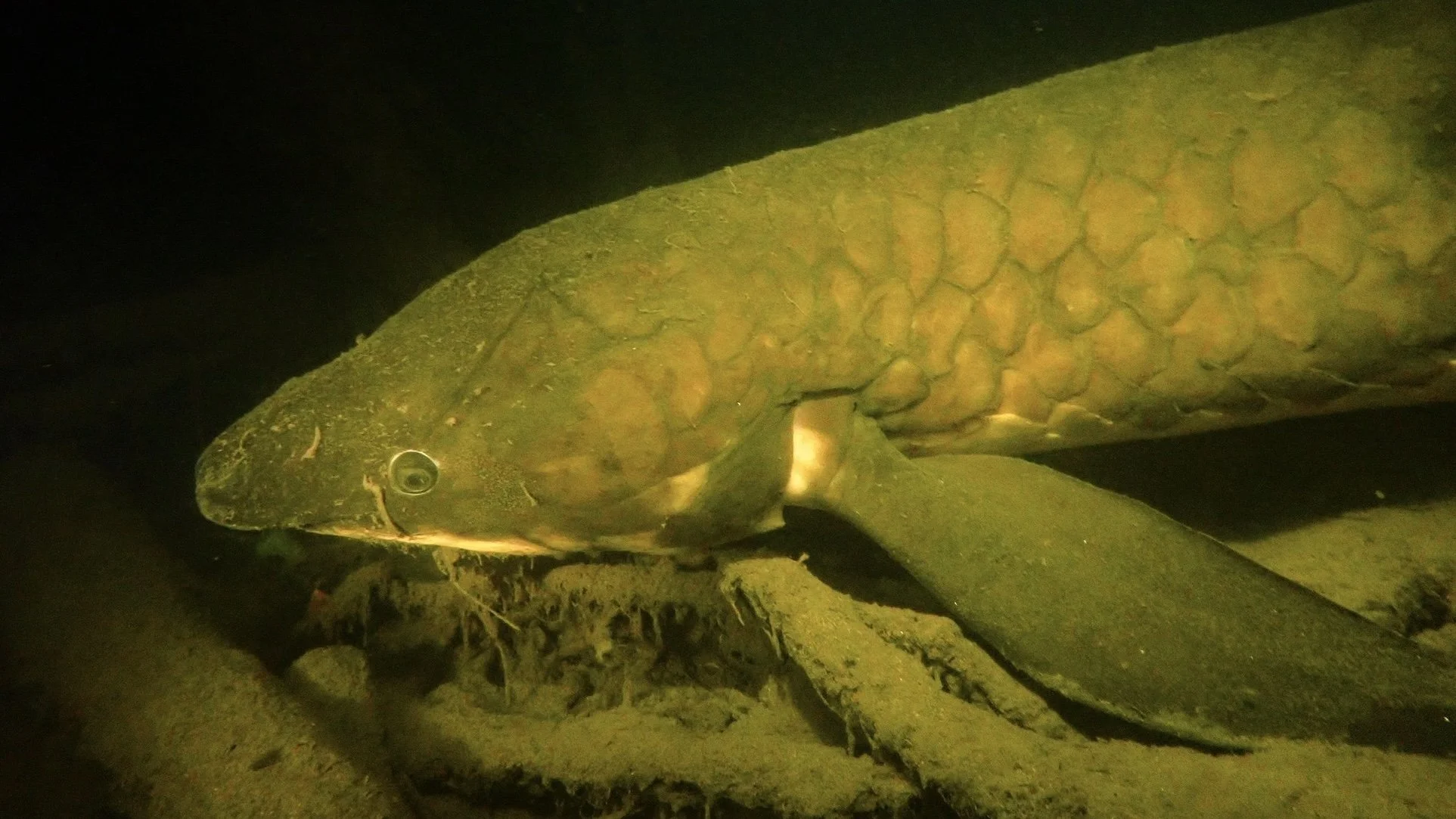

The ancestors of both lungfish and tetrapods belonged to a group called the lobe-finned fish; those with paired, fleshy fins supported by a robust internal skeleton. Unlike most bony fish — whose fins are anchored to their bodies by several bones — lobe-finned fish have fins attached via a single bone, comparable to the humerus in tetrapods. The lungfish, for instance, has one bone that supports a long, slender fin. But there’s another example of this transitional stage in limb development, found in the anatomy of a “living fossil” still swimming our deep oceans.

The coelacanth was believed to have been extinct for some 65 to 70 million years until a live one was discovered in 1938. Though not a direct ancestor of tetrapods, the coelacanth exemplifies what early lobe-fins might have looked like: each of its limbs consisting of a single humerus, then two bones (radius and ulna), then many smaller branching bones, arrayed more like a typical fish fin — memorably described by Neil Shubin, the discoverer of Tiktaalik, as a “one bone–two bones–lotsa blobs digit arrangement.”⁴

Using the fossil record, we can trace the transition from fins like these to the first limbs capable of supporting weight on land.

Late Devonian (385–360 mya) lobe-finned fish and amphibious tetrapods.

© Dave Souza (Original), Pixelsquid (Vector) / Wikimedia Commona

Of course, neither the lungfish nor the coelacanth are themselves transitional fossils — they’re not the same species that first ventured onto dry land. They — along with mudskippers, walking catfish, leaping blennies, and cave angels — are modern animals, shaped either by convergent evolution, or by the long retention of ancient features (hence “living fossils”).

No single, living species can tell the whole story of how vertebrates crawled onto land.

Yet if we take the terrestrial behaviour of a mudskipper, the lungs of a lungfish, the fin bones of a coelacanth, plus the fused pelvic girdle and locomotion of the cave angel, we can assemble a clearer picture of how those primeval, pioneering fish might have evolved, and made the leap, or climb, from water to land. Each of these living fishes offers a line, a chapter, a verse in the long evolutionary epic.

The abyssal angel climbs up toward the heavens, but remains forever trapped in its dark underworld. And yet, from within that darkness, it has shed light on a story some 375 million years in the telling.

¹ The likelihood of fossilisation varies depending on who you ask.

Some scientists estimate that under 8-10% of animals are fossilised, while others argue that it’s as little as one-tenth of 1% (or 0.001%). The scarcity of fossils in general is compounded by another issue: the scarcity of specific types of fossils. The process of fossilisation favours certain structures over others. Hard parts like bones, teeth, and shells are far more likely to be preserved than soft tissues, feathers, or entire organisms with no mineralised structures at all. The environments that animals lived in also matters. Organisms that lived in sediment-rich aquatic settings had a better chance of being fossilised than those that lived in forests, mountains, or deserts, where remains were more likely to decay or be scavenged before becoming buried.

² We also see convergent evolution between flying squirrels, colugos (flying “lemurs”), and the marsupial gliders. All have independently evolved their gliding membranes. And although each has their slight variations — the cogulo's membrane extends between its hind leg and tail, for instance — they’ve all converged on a strikingly similar solution for traversing the treetops.

A few other examples of convergent evolution include:

The spine-covered backs of hedgehogs, Old World porcupines, New World Porcupines (evolved separately), some tenrecs, and a few species of rats.

The mole-like appearance of “true” moles, African golden moles, and marsupial moles.

A form adapted for ant-eating — bulky bodies, hunched backs, long thin snouts with worm-like tongues — in anteaters, armadillos, pangolins, and echidnas.

The streamlined swimming shape of sharks (fish) and cetaceans like dolphins (mammals) — also ichthyosaurs (reptiles), if we’re including extinct creatures.

A characteristic crab-like shape has evolved at least five separate times in decapod crustaceans (a phenomenon so prominent that it has a name: carcinisation).

³ The known, living lobe-finned fish are limited to two species of coelacanths and six lungfish species: one species in Australia, one in South America, and four in Africa. The Australian species is unique for having fully-functioning gills and only one lung. The rest have atrophied gills, making them obligate air-breathers, for which purpose they all have paired lungs.

⁴ The fossil of Tiktaalik roseae was discovered in 2004 on Ellesmere Island in Nunavut, Arctic Canada. Living around 375 million years ago, during the Devonian period, it is considered a transitional form between lobe-finned fishes and early four-legged vertebrates (tetrapods), possessing both fish-like traits (scales, fins, and gills) and tetrapod-like traits (a neck, flat head, rib bones, and limb bones resembling wrists). The “gap” that it fills is between fully aquatic fish like Eusthenopteron and more amphibian-like Acanthostega.

Where Does It Live?

⛰️ Karst caves.

📍 Northwestern Thailand.

‘Vulnerable’ as of 23 Feb, 2011.

-

Size // Tiny

Length // <3 cm (<1.2in)

Weight // N/A

-

Activity: N/A

Lifestyle: Solitary 👤

Lifespan: N/A

Diet: N/A

Favorite Food: Cave micro-organisms and organic matter ¹

-

Class: Actinopterygii

Order: Cypriniformes

Family: Balitoridae

Genus: Cryptotora

Species: C. thamicola

-

This strange fish goes by the scientific name of Cryptotora thamicola; its specific name derived from the Thai word for ‘cave,’ tham, and the latin for ‘to inhabit,’ colere. The cave angel is a cave-dweller, a true troglobite.

It was first discovered in Tham Susa, a karst cave in northwestern Thailand, and was subsequently found in other nearby cave systems. Its total known range spans some 200 kilometres², but its actual inhabited range is a mere 6 kilometres² — whether its various cave systems are connected is unknown.

Its habitat is dark and dank, made up of limestone pockmarked with holes, chambers, and vertical passages, where eroding waters trickle, seep, and plunge through narrow gaps and into pits. It’s the kind of environment that produces one of the strangest fishes on Earth.

For one, the cave angel is partially translucent, completely eyeless, and measures about the size of a paper clip. That’s not why it’s so strange, however: out of all known fish (approximately 35,000 species), the cave angel is the only one with a pelvic girdle fused to its vertebral column. This is a structure strikingly similar to that of modern salamanders and early land vertebrates.

In most fish, the pelvic girdle — the bony or cartilaginous structure that supports the pelvic fins — is a loose, floating element. But in the cave angel, its connected pelvic girdle lets it exert force from its pelvic fins and through its body, to push against rock, and to climb. Hence its other name: the “waterfall-climbing fish.”

-

Tetrapod-like pelvic girdle in a walking cavefish by Brooke E Flammang, et al.

The biomimetic potential of novel adaptations in subterranean animals by Thomas Hesselberg

Grotto Map — Tham Susa

Florida Museum — Walking catfish

New Scientist — Blennies

The evolutionary history of the development of the pelvic fin/hindlimb by Emily K Don, et al.

Smithsonian Ocean — Coelacanth

Australian Museum — Coelacanth

Australian Museum — Australian lungfish

University of California Museum of Paleontology — Lungfishes

-