Kauaʻi Cave Wolf Spider

Adelocosa anops

The Kauaʻi cave wolf spider has adapted to the lightless caverns of southern Kauaʻi by losing its eyes entirely. It creeps slowly — consuming ~40% as much oxygen as surface-dwelling wolf spiders — pursuing its primary prey: the Kauaʻi cave amphipod, a blind crustacean endemic to the same caves.

Most spiders have eight eyes, with those that actively hunt tending to boast the best vision.¹

A typical wolf spider has its eyes arranged in three rows: four small, forward-facing eyes just above its massive chelicerae, two very large eyes above those, and two medium-sized eyes atop its convex head. The smaller eyes are simple, used to detect light and movement, while the larger ones provide the wolf spider with acute visual detail and are less like the eyes of insects — not multi-faceted, compound eyes — but camera-type eyes, similar to ours.

Shine a torch across a field or garden at night, and you may witness several pairs of eyes staring, glowing, back at you. Four of a wolf spider's eight eyes, its largest two most prominently, feature a tapetum lucidum that reflects light back into their retinal cells, creating a clearer image out of the little light available — analogous to the reflective structure found in the eyes of nocturnal animals like cats and deer. A wolf spider hunts in the dimness of dusk or the darkness of night, employing its octet of keen, reflecting eyes to chase or ambush prey.

Not every spider is so sharp-sighted.

Orb-weavers — those spiders known for their web-building prowess — also have eight eyes, but none are very large, specialised, or sharp. An orb-weaver's world is its web, after all, and it employs more appropriate tactile senses to "see". Coneweb spiders, too, weave webs — if less impressive, somewhat tangled webs — and have only six eyes. As do the scavenging recluse spiders, their eyes arching across their faces in a U shape. A few species of armoured spiders in the genus Tetrablemma have four eyes, and many so-called lungless spiders in the family Caponiidae have just two. Given such ocular variety, perhaps it's unsurprising that there are species of spiders with no eyes whatsoever.

The No-eyed Big-eyed Wolf Spider

One such species is found exclusively on the Hawaiian island of Kauaʻi, where it's known as the pe'e pe'e maka 'ole spider or, simply, the blind spider.

Formed by volcanic activity some 5 million years ago, Kauaʻi has since settled down (it's no longer volcanically active), but the history of its tumultuous creation is carved through the island's very core. Lava tubes, once running with molten rock, now solidified into dark tunnels, weave beneath parts of the island like spider webs. In the tunnels and caves of the Koloa Basin — underground spaces carved by fire and water — lives the Kaua‘i cave wolf spider. It is unique among the wolf spiders. It belongs to a family of spiders with some of the sharpest eyesight, yet it has no eyes at all.

The presence of a tapetum lucidum in the eyes of some nocturnal mammals and spiders — similar in function, if not in structure — is an example of convergent evolution: both groups faced the same problem (needing to see in the dark), and converged upon the same solution separately. But what if your world is so dark that, no matter how efficiently your eyes capture light, you still couldn’t see? What if there was simply no light to capture? Another example of convergent evolution can be seen among cave-dwelling animals, from fish (Mexican tetra) to amphibians (olm), crustaceans (blind cave crayfish), molluscs (blind cave snails), and arachnids.

Economically, it makes sense. Eyes are expensive organs to develop, and if they have no use, that energy can be invested elsewhere — not to mention that eyes are vulnerable to injury and infection. Leaving the light behind for pitch black caverns, all these animals lost their ability to see. Some lost their eyes completely.

Blind Hunting

Most wolf spiders — those on the surface, that is — adapted to the darkness of night by growing large eyes with tapeta lucida. The cave wolf spider adapted to the complete darkness of caverns by losing all vestiges of its eye structures.

Despite its blindness, the Kaua‘i cave wolf spider is still an active hunter.² This 16-millimetre (0.6-in) wolf stalks its 8-millimetre (0.3-in) prey through humid caverns, slick with moisture. The spider's quarry, the Kaua‘i cave amphipod, is a translucent crustacean with a bulbous backend and pairs of legs splaying downward and up. It too is blind, although it hasn't yet lost its eyes completely.

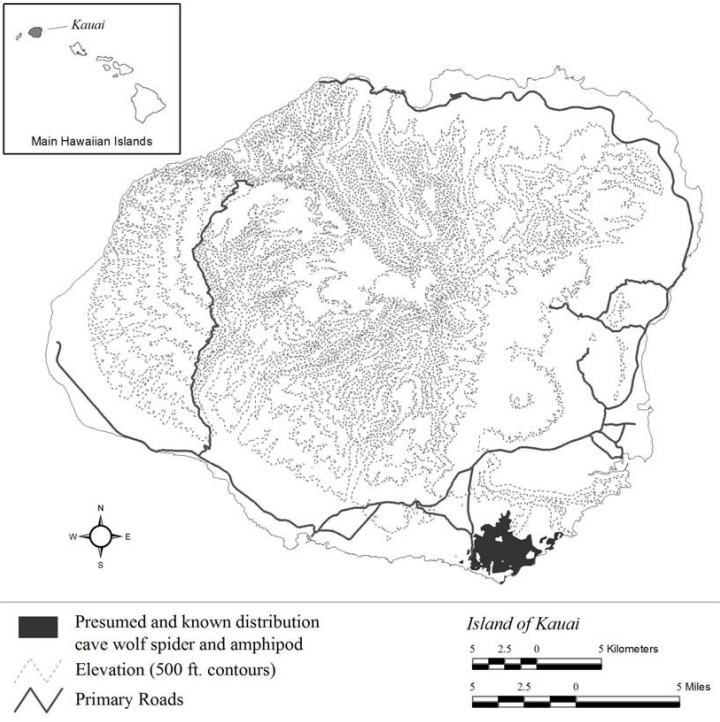

These subterranean denizens — the blind spider and blind amphipod — were discovered together in 1971. Restricted to a 10.5 square kilometre (4 mi²) area of lava-formed caves, the two species have been locked in an evolutionary arms race, predator and prey, evolving to hunt and hide in the pitch dark.

The cave wolf spider prowls the cave floor, moving slowly and purposefully. In lieu of sight, it hears and feels, tastes and smells with its many copper-coloured legs. From the ends of each leg sprout unusually long and silky sensory hairs known as trichobothria. Each sensory hair is anchored in something like a ball-and-socket hinge — the shaft rising outward, the nerve ending embedded at its base. Every vibration and air current moves the sensory hair, shifting the position of its end in the socket ever so slightly, and firing a signal down the nerve.³ The many trichobothria on each of its eight legs tell the spider more about its surroundings than a set of eight eyes ever could. Additionally, the tips of its legs likely bear chemoreceptors — the spider tastes the surface it treads on with every step.

A hunt may go something like this:

A blind cave amphipod is feasting on rotting plant detritus that has washed into the cave. Not far off, a blind cave spider crawls through the dark. It feels the airborne vibrations as the amphipod feeds. It tastes the tracks the amphipod left behind it. The spider can't see its prey, but it knows exactly where it is. The spider creeps up, ambushes the amphipod, grabbing it, bringing it towards its chelicerae, and sinking its large fangs into its armoured carapace. The amphipod is too slow, its senses too dull, for the cave wolf spider.

Silk for Seduction & Safekeeping

The cave wolf must find more than amphipods in the dark. It also has to seek out other spiders —- not to eat (although it does that too) but to court and couple.

Wolf spiders don't use their silk to build shelters or traps. Rather, silk is a tool of seduction. A female lays down a pheromone-laden dragline of silk for potential mates to follow by scent. The blind cave wolf may actually have an easy time of it, given its heightened non-sight senses. The species’ mating habits have yet to be observed, but they're probably not very romantic.

Surface-dwelling wolf spiders mate in spring. Small males perform courtship dances to entice the larger females, waving their legs and pedipalps in complex patterns — doing their best to appear like attractive mates, rather than enticing meals. Depending on the species, they might court outside a female's burrow at night or under the spotlight of the sun on a bright day. Male cave spiders certainly don't perform in the sun. Maybe they don't perform at all, given that females wouldn't see their gestures. Or perhaps their courtship has changed to suit their tactile senses. Whatever the case, males and females come together, and eggs are eventually fertilised.

Wolf spiders use silk for seduction, yes, but silk is also the tool of a dedicated mother.

Once he’s made his genetic investment, the wolf spider father promptly scuttles away (or is eaten). The mother then begins to weave, using her papery silk to craft a globular egg-sac which she straps to her back with stronger silk lines. She carries her brood around wherever she goes until they hatch, and then continues to lug them around on her abdomen until they can fend for themselves. (Wolf spiders are the only spiders known to carry their young on their backs.) Most species will mother anywhere between 100 and 300 spiderlings per brood. A cave wolf mother, meanwhile, has 30 or fewer. To use the technical term, she opts for a more K-selected reproductive strategy; the resources in the cave are stable but limited, so while she has fewer offspring, a higher percentage are likely to survive.⁴ In this respect, the cave wolf spider is more like us humans than other wolf spiders.

Silken Sailing

Wolf spiders may not build spectacular webs like orb-weavers, or craft weapons like net-casting and bolas spiders, but they do use their versatile silk to seduce mates, carry their offspring, and even take to the skies.

You're unlikely, fortunately, to witness a skyful of floating adult wolf spiders, but soon after hatching, the tiny wolf spiderlings are light enough to "balloon" through the air. They do so by releasing threads of silk to catch wind currents. A strong enough gust pulls at their parachutes and snatches them into the air, where they'll float until they touch down in some other location. Such a journey may even take them across seas to new lands.

In their subterranean world, cave wolf spiderlings will likely never fly. But their ancestors probably did.

Today, close relatives of the cave wolf spider live on adjacent Hawaiian islands, and it's hypothesised that their ancestors dispersed from one island to another as little ballooning spiderlings.

The voyages of the Polynesians, the discoverers of Hawai'i (among many other Pacific islands), are some of the most extraordinary feats of human exploration and navigation. The blind arachnids of Kauaʻi undertook a journey that, unintentional as it might have been, is nearly as astonishing. Their surface-dwelling ancestors, with giant eyes to hunt at night, birthed young who took to the air on parachutes of silk and were swept out to sea on the winds. The majority of them probably perished as they landed among the waves, but a few were lucky enough to make landfall. Then it happened again and again. Over a span of what was likely many thousands of generations, the spiders island-hopped until they reached Kauaʻi, where some intrepid individuals crept into the island's caves and crevices and never resurfaced. Today, no longer do they live in the world above, no longer do they fly across the sky, these cave spiders, in their lightless world, that long ago lost their eyes.

Endangered

Wolf spiders are some of the most common arachnids on Earth, found on every continent except Antarctica. But of the nearly 2,500 known species, there's none like the Kaua‘i cave wolf spider and few quite so rare — quite so endangered. Not only is the species restricted to a single island (Kaua‘i), as well as a specific region (Koloa), but the cave wolf spider has only been regularly seen in four caves: Koloa Caves 1 & 2, Kiahuna Mauka Cave, and Cave 3075C.

These caves feature stable climates with high humidity; a necessity for housing creatures that would otherwise quickly dessicate. Even a modicum of airflow, a slight breeze, is enough to reduce humidity by a dangerous degree for both the cave spider and its amphipod prey. Indeed, in caves with sub-optimal humidity, the Mediterranean recluse spider reigns. With a venomous bite capable of causing necrosis, this invasive species is much less specialised, outcompeting the relatively harmless cave spider, thriving in the downfall of the troglobites.⁵

During the past couple centuries, much of the area above Kiahuna Mauka Cave was turned into a sugar cane field and then a golf course/lawn — changes that altered surface vegetation and allowed drier air to flow into the cave. This was bad for the cave spiders, certainly, but the problem was especially dire for the amphipods, who rely on vegetation detritus swept in from the surface. Agricultural fields and golf courses meant poor eating for the amphipods, and they were forced to subsist on whatever old, decaying roots were lying around (plus supplemental food provided periodically by biologists). Of course, if the food source dried up for the amphipods, causing them to die out, the cave spiders would likely follow soon after.

That would scarcely matter, however, if the cave itself dried up.

Between the years of 1999 and 2003, a drought hit Kaua‘i, lowering humidity even in its subterranean caverns, and the cave spider disappeared completely from Kiahuna Mauka Cave, leaving it to the invasive recluses. Such changes — land alteration, invasive species, and drought — likewise threaten the cave wolf’s other handful of known refuges.

Later, once conditions returned to their humid equilibrium, surveys of Kiahuna Mauka Cave found that the cave wolves had returned. A native plant restoration program was begun, turning the area above the cave from bare lawn to native bush. The effort seems to have borne some results, as Kiahuna Mauka Cave now harbours the second largest observed population of Kauaʻi cave amphipods. And the return of the wolf spiders themselves was very reassuring; proof that they could recolonise caves once conditions improved.

A cave survey (of Koloa Cave 2) in 2016 found 41 individuals. Both sub-adult and adult spiders were seen, some of them mothers carrying silk-woven sacs of eggs — indicators of a healthy population. And there's reason to hope that, with their ability to tolerate low-oxygen, high carbon dioxide environments, more cave wolf spiders may yet dwell, blind in the dark, in the impenetrable passages and unsurveyed caverns beneath Kauaʻi.

¹ Wolf spiders (family Lycosidae) have exceptional vision for arachnids, but they're not the only ones. Huntsman spiders (family Sparassidae) — that are likewise active predators, and occasionally (fittingly) hunt wolf spiders — also have great vision, but not quite as impressive as that of jumping spiders (family Salticidae).

A jumping spider's two primary eyes are forward-facing and massive, providing the spider with a clear telephoto image for tracking the movement of prey in full colour. Human vision is estimated to be 5 to 10 times better than a jumping spider's, which does sound like a big improvement, but jumping spiders are also over a million times smaller than a human.

² Unlike epigean (above-ground) wolf spiders, which are swift-moving predators, the cave wolf moves slowly, deliberately, and, much of the time, it is completely motionless. Its lower metabolic rate, requiring only ~40% as much oxygen as surface-dwelling species, allows it to survive in low-oxygen and high carbon dioxide conditions, but it evidently comes with a more stringent activity budget.

³ For an insight into just how sensitive filiform hair mechanoreceptors can be (in insects, in this case):

"According to recent findings in cricket cercal hairs, they are the most sensitive of all known sensory organs. Shimozawa and associates (1998b) at the University of Sapporo determined the minimal amount of mechanical energy needed to elicit a nervous impulse by hair deflection as 4×10⁻²¹ Ws. This value tells us that the cricket thread hairs are more sensitive by a factor of 100 than the most sensitive photoreceptor cells which respond to a single quantum of light (ca. 3×10⁻¹⁹ Ws). As early as 1982, Thurm concluded that threshold energy in thread hairs is smaller than the energy contained in a single quantum of green light (Thurm 1982)." (Barth, 2000)

Although the cave wolf spider is an arachnid (not an insect), its mechanoreceptive structures likely operate in a very similar manner.

⁴ As opposed to r-selected species, which frequently live in highly variable environments and so prioritise having many offspring with little to no parental care, typically accompanied by short lifespans. Examples of r-selected species include many rodents, rabbits, most fish and frogs, insects, jellyfish, etc.

⁵ A troglobite is a species that lives solely in caves. These include the afore-listed set of blind species: the olm, blind cave crayfish, blind cave snails, and Mexican tetra (the blind variant, at least).

Troglobites are distinct from troglophiles (cave lovers), who prefer caves but can survive outside them, and trogloxenes (cave guests), who visit caves but don’t live in them. They’re also not to be confused with troglodytes, which are either prehistoric cave-dwelling humans or modern ones that are especially ignorant or reclusive.

Where Does It Live?

⛰️ Moist caves formed by lava and water.

📍 The Koloa Basin in southeastern Kauaʻi, Hawaii.¹

-

Size // Tiny

Length // 16 mm (0.6 in)

Weight // N/A

-

Activity: Most wolf spider are nocturnal — this one never sees the sky

Lifestyle: Solitary 👤

Lifespan: N/A

Diet: Carnivore

Favorite Food: Blind cave amphipods 🦐

-

Phylum: Arthropoda

Class: Arachnida

Order: Araneae

Family: Lycosidae

Genus: Adelocosa

Species: A. anops

-

The Kauaʻi cave wolf spider is solely found on the Hawaiian island of Kauaʻi, and then only within a southern region known as the Koloa Basin, and, within the basin, has been regularly seen in just four caves.

This species is one of the few spiders that has lost its sight, and all vestiges of its eyes completely. Why would it need them, anyway, when it lives in lightless caverns and old lava tubes?

The Kauaʻi cave wolf spider doesn’t let a lack of sight get in the way of being an active hunter. Its primary prey is a blind cave amphipod (a kind of tiny crustacean), which is endemic to the same caves. The cave wolf hunts using extremely sensitive sensory hairs and chemoreceptors on its legs, which catch the slightest vibrations and “taste” the surface it stalks across.

However, unlike above-ground wolf spiders, which are swift-moving predators, the cave wolf moves slowly, deliberately, and, much of the time, it is completely motionless. Its lower metabolic rate, requiring only ~40% as much oxygen as surface-dwelling species, allows it to survive in low-oxygen and high carbon dioxide conditions, but this evidently comes with a more stringent activity budget.

Low-energy as the cave wolf may be, it makes for quite the dotting parent. Or rather, mother. (Little is known about the reproductive behaviour of this species, but in other wolf spiders, the father does not participate in child rearing, and is sometimes eaten by the mother after mating.) A female cave wolf will weave a globular egg sac in which she’ll carry around her eggs, and even when they hatch into spiderlings, she’ll look after them for a bit until they can fend for themselves.

Today, close relatives of the cave wolf spider live on adjacent Hawaiian islands, and it's hypothesised that their ancestors dispersed from one island to another as little ballooning spiderlings — young spiders that release threads of silk to catch wind currents that carry them away.

The Kauaʻi cave wolf spider is harmless to people, however, when conditions in its cave change — say, when a cave dries out due to a draft or drought — it is often outcompeted by the invasive and dangerous Mediterranean recluse spider.

Indeed, the cave wolf disappeared from one of its few known homes, Kiahuna Mauka Cave. The landscape above had been altered into a sugar cane field and then a golf course/lawn. This meant that native vegetation no longer ended up in the cave, and the blind cave amphipods, which rely on that vegetation for food, began to starve. If they went, so would the spiders. And the spiders did — they vanished from the cave — but not just due to a prey shortage; a drought hit the island between 1999 and 2003. Fortunately, once moisture returned, so did the cave wolves, although the species is still listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act.

‘Endangered’ as of 01 Aug, 1996.

-

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service - FWS ECOS

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service - FWS.gov

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service - FWS ECOS

THE CAVERNICOLOUS FAUNA OF HAWAIIAN LAVA TUBES, 3. ARANEAE (Spiders) By Willis J. Gertsch

Bishop Museum — Kaua‘i cave amphipod

Australian Museum — How spiders see the world

Northern Woodlands — Spider eye function

Kauai Historical Society — History of Kauai

Australian Museum — Wolf spiders overview

National Geographic — Pheromones in wolf spider mating

Chesapeake Bay Program — Wolf spider field guide

EurekAlert — Wolf spider research news

Wildlife Trusts — Wolf spiders in UK wildlife

Backyard Buddies — Wolf spiders in Australian gardens

-

Cover Photo (Gordon Smith / BioLib.cz)

Text Photo #01 (© Thomas Shahan / iNaturalist)

Text Photo #02 (© MatiasG / iNaturalist)

Text Photo #03 (© Nicky Bay / iNaturalist)

Text Photo #04 (© Marshal Hedin / iNaturalist)

Text Photo #05 (© William P. Mull / Bishop Museum)

Text Photo #06 (© William P. Mull / Bishop Museum)

Text Photo #07 (© Adriano Losso & © Manfred Auer / iNaturalist)

Text Photo #08 (© Steve Creek / stevecreek.com)

Text Photo #09 (© Julius Mueller / Getty Images)

Text Photo #10 (© Alchetron.com)

Text Photo #11 (© Ryosuke Kuwahara / iNaturalist)

Text Photo #12 (© Friedrich G Barth and © Encyclopedia Britannica)

Slide Photo #01 (© Gordon Smith / BioLib.cz)