Bonin White-Eye

Apalopteron familiare

The Bonin white-eye is endemic to the isolated Bonin Islands of Japan. On these islands, which are bereft of several types of birds, this white-eye evolved to occupy their niches: foraging among branches like a tit, on trunks like a woodpecker, and on the ground like a robin.

Japan is an archipelago country comprising some 14,125 islands.¹

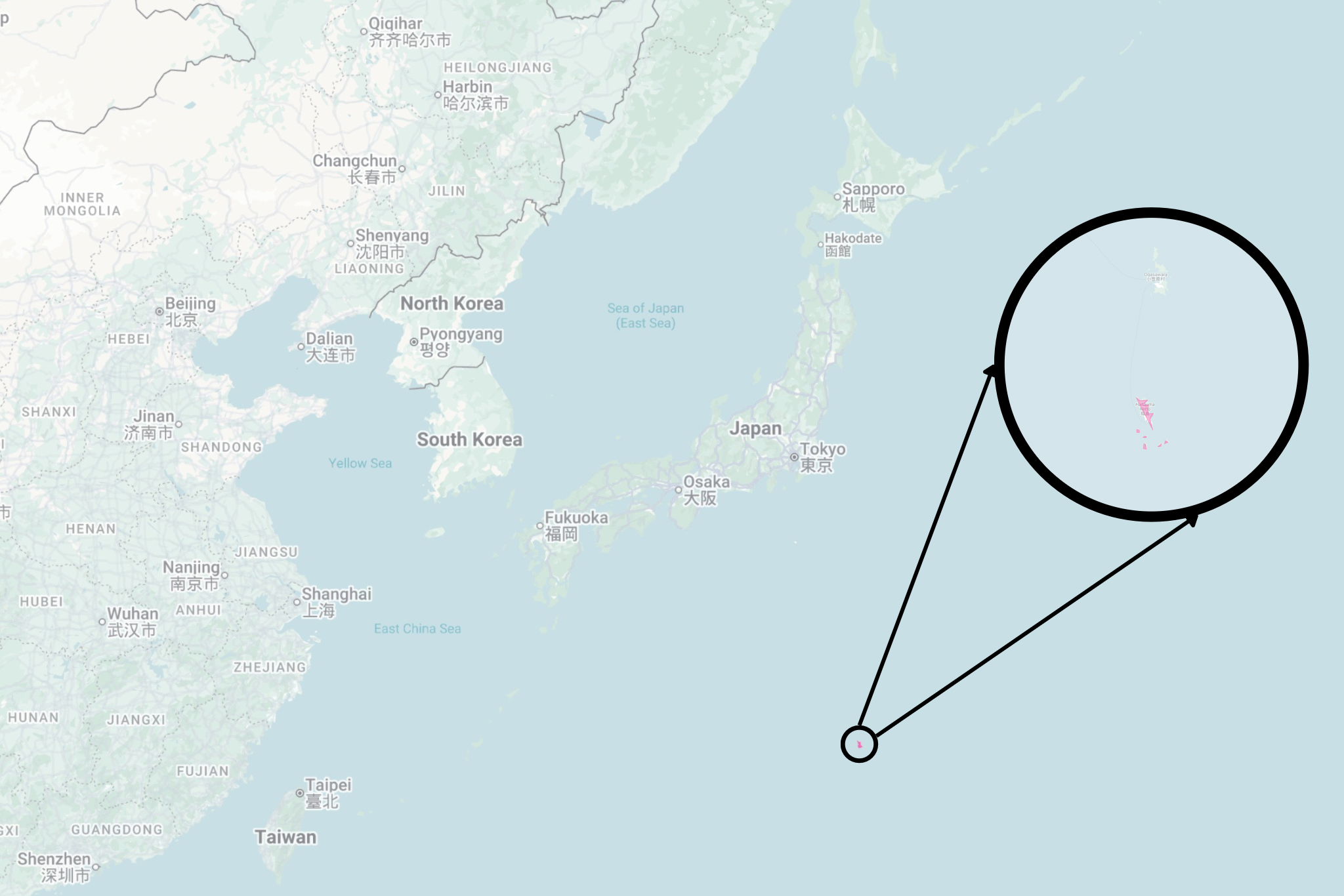

While the country’s main body is made up of just four major islands — Hokkaido, Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu — thousands of satellite islands speckle the surrounding seas, scattered here and there like sets of fortune-teller’s bones or strung in arcs like stretched necklaces of pearls. The Oki Islands, Gotō Islands, Ryukyu Islands, Izu Islands; Japan extends further than you might expect, reaching northwest towards mainland Asia, snaking down towards Taiwan, and casting out into the open Pacific. You’d be forgiven for missing this extended Japan, given that many of these isles are little more than specks on a map, yet together they constitute an extensive, if somewhat scattered realm.

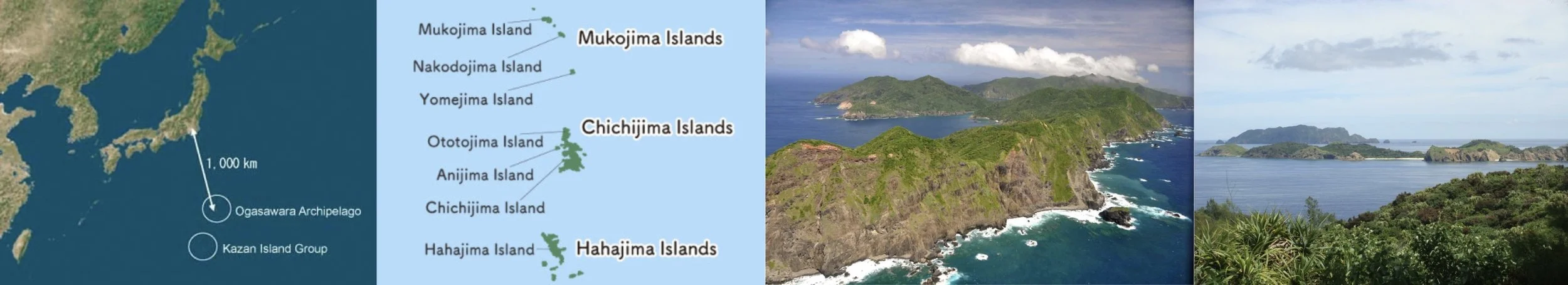

Bonin

Around 1,000 kilometers (620 mi) south of Tokyo lies among the most isolated of this realm’s reaches: an archipelago of over 30 volcanic islands known as the Ogasawara or Bonin Islands. They little resemble the rest of Japan. Their climates are subtropical and oceanic: sun-baked, salt-sprayed, and wind-lashed. There are no towering cedar trees here, nor extensive rice paddies. The Bonin forests are low and open, made up of unfamiliar flora. And the fauna here is equally un-Japanese: no snow monkeys or raccoon dogs, no cranes or storks, no bears or giant salamanders.

Much of the Bonin fauna is an oceanic fare of marine species (green sea turtles, humpback whales, coral reef fish) and pelagic birds (brown boobies, golden-plovers, black-footed albatrosses). Hopping and fluttering amidst the Bonin fan palms and thick waxy shrubs are blue rock-thrushes and black wood-pigeons; terrestrial birds, yes, but well-accustomed to travelling between islands, with the latter being found on many of Japan’s isolated isles.

But not all birds are such nomads.

When a bird finds itself stranded on such an isolated set of islands, it might evolve to become more sedentary, to settle, and, over time, diverge from its original population. It changes its appearance and behaviour, adapting to this different environment, becoming an utterly unique, endemic species.

Something like that must have befallen the ancestor of the Bonin white-eye.

Bulbul, Honey-Eater, White-Eye

Isolated on the Bonin Islands, what traits did this white-eye evolve?

It’s a small bird, only some 13 centimetres (5 in) long. Its green-yellow plumage fades into foliage and disappears in the sun’s rays. And the Bonin white-eye’s “white-eyes” — the rings of white feathers around each eye — are overshadowed by black triangular patches, making the bird appear like it's wearing a superhero or wrestler mask.

All of these characteristics tell us little about this species’ evolutionary history, however, if we don’t have some point of comparison. We need to know how it began, to see how it has changed.

Who were its ancestors? Who are its closest relatives?

You might expect the answer to be relatively simple and straightforward, given that we’re talking about a relatively simple and straightforward songbird, but the white-eye belongs to (by far) the largest order of aves — the Passeriformes, or perching birds, with more than 6,500 species — and their relationships aren’t always easy to parse.

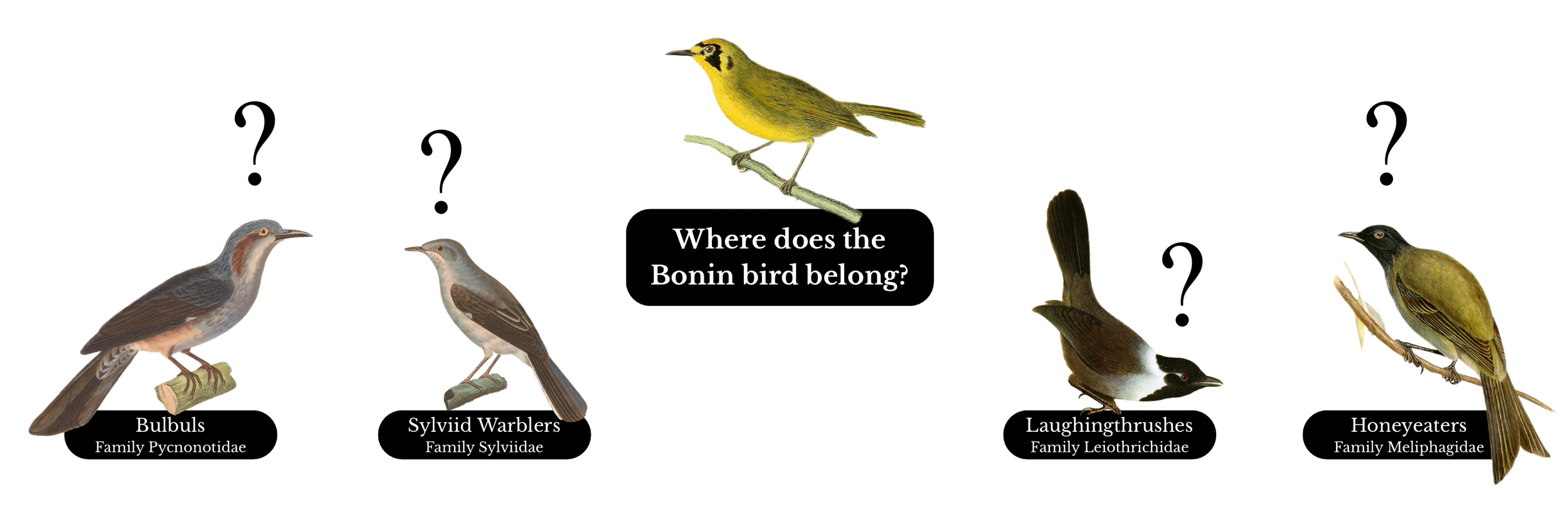

The taxonomic history of the Bonin white-eye is somewhat fraught (an understatement, really). In fact, the Bonin white-eye wasn’t even a white-eye until fairly recently.

It was first described in 1831 as Ixos familiaris, and assigned to the bulbul family (Pycnonotidae). Bulbuls are relatively large songbirds — the brown-eared bulbul, for instance, reaches around 28 centimetres (11 in) in length — and, like most Asian bulbuls, it is a fruit-eater, gathering in flocks and sweeping through forests, orchards, and parklands.

While the Bonin white-eye is not even half as large, it’s still relatively bulky compared to other white-eyes, its diet is predominately fruity (papayas, bananas, mulberries, etc.), and it does feed in more open habitat — on the ground and on tree trunks — doing so in a slower, less frenetic manner than might be expected of a white-eye, which tend to be frenzied, fluttering balls of energy that dash from twig to twig. Perhaps that was the logic behind its bulbul-hood.

Logical or not, in 1854, it was moved into its own unique genus: Apalepteron, the same genus it’s in today. However, it was initially created within the Sylviidae family — today a group of small songbirds found across Eurasia and Africa, back then a kind of “wastebasket” taxon for the birds that didn’t obviously fit elsewhere. As of 1854, the Bonin white-eye was essentially in the taxonomic junk drawer.

But it wasn’t long (1882) before the Bonin white-eye was moved again; back to the bulbuls, this time into the genus Pycnonotus alongside species like the streak-eared and red-whiskered bulbuls. There it sat for several decades, occasionally given another glance and guess — in 1946, for instance, it was proposed that the Bonin white-eye’s closest relatives were actually in the genera Minla and Actinodura, today both in the laughingthrush family.²

Then a detailed study (Deignan 1958) was published describing the Bonin white-eye’s characteristics: its “pervious nostrils,” not separated by an internal bone, “quasi-booted tarsi,” legs partially covered in feathers, “short, somewhat recurved, bristle-like feathers on the front and throat,” the construction of a cup-nest and the laying of 1–4 pale greenish-blue eggs inside, and, most revealingly (according to the study), the particular structure of its tongue. These facts being presented, the study concluded “that Apalopteron is…a fairly typical genus of the Australasian Meliphagidae or honey-eaters.” And so it was that, in 1958, the Bonin white-eye became a honey-eater.

Assigned to the bulbul family, thrown temporarily in the bin, then retrieved and restored, before being shoved among the honey-eaters — the Bonin white-eye has been tossed between families like some unwanted avian orphan. It was only in 1995 that it finally found its home, its true family.

“Deignan's study seemed convincing, but there are no honeyeaters in the Philippines, Taiwan or other islands in the northeast Pacific Ocean. Conversely, white-eyes occur on many temperate and tropical islands in the western Pacific, including Japan and nearby islands. Deignan's list of morphological characters includes some that are widely shared among passerines and the tongue structure is not limited to “typical honeyeaters.”³

This quote comes from a 1995 study (Springer, et al. 1995) which outlined the pitfalls of using morphological features to place a passerine bird into one family or another, and then presented behavioural and genetic evidence (from 12S rRNA sequences) to, once and for all, assign the Bonin white-eye to the family Zosteropidae, with the white-eyes.

Widespread White-Eyes

Why was the Bonin white-eye so difficult to place?

As mentioned up top, species change when they find themselves trapped on islands — if not by adaptation to a new, fundamentally different environment, than by genetic drift (perhaps nudged down a particular path by the ‘founder effect’).⁴

The Bonin white-eye had clearly accrued enough differences in its isolation as to befuddle more than a century of naturalists and taxonomists.

The white-eyes are small songbirds, often around 12 centimetres in length, usually wearing olive-yellow-grey plumage, and named for the rings of white feathers around their eyes. They belong to the Zosteropidae family — along with crested birds called yuhinas, some little-studied birds known as heleias, a few babblers, and one “black-eye,” with eye-rings of black instead of white — altogether comprising over 130 species that range across South, East, and Southeast Asia, Oceania, and Sub-Saharan Africa.

The following is a description of the Bonin-white eye.

“Apalopteron has longer tarsi and forages among twigs and leaves like white-eyes and tits (Parus), on trunks and branches like nuthatches and woodpeckers and on the ground like small robins (Erithacus)…The diversity in the foraging ecology of Apalopteron is probably the result of niche expansion associated with the absence of tits, nuthatches, woodpeckers and small robins.” (Springer, et al. 1995)

In other words, since many types of birds are completely absent from the Bonin islands, the Bonin white-eye took over the niches they would normally fill — foraging in canopies, on trunks, and along the ground — becoming more of a generalist jack-of-all-trades ave. The Bonin white-eye evolved to be more similar to other types of birds — “familiare,” as per its specific name — so it’s no wonder it was difficult to place among them. Its insular evolution, towards a generalist lifestyle, masked its evolutionary history.⁵

The isolation of the Bonin white-eye is extreme, but its evolutionary history is not especially unique among the Zosteropidae. These little birds have made a habit of hopping seas, settling new lands, and forming new species.

The aforementioned mountain black-eye, with its atypically dark eye-rings, is endemic to the high mountains of Borneo. The giant white-eye, only a relative “giant” at 14 centimetres (5.5 in) long, is endemic to the Pacific islands of Palau. The teardrop white-eye is endemic several times over: confined to Micronesia, restricted within Micronesia to the Caroline Islands, within the Caroline Islands to the Chuuk Atoll, within Chuuk to the Faichuk island group, within Faichuk to the island of Tol, and on Tol, it can only be found on the summit of Mount Winipot. The Mauritius grey white-eye and Mauritius olive white-eye are endemic to the African island of Mauritius (the former home of the dodo), and both species have close relatives just one island over: the endemic Réunion grey white-eye and Réunion olive white-eye — that’s four endemic white-eyes on just two islands.

There’s the Fiji white-eye, Solomons white-eye, Socotra white-eye, Seychelles white-eye, São Tomé white-eye, Wangi-wangi white-eye, and many more. (Below is a map with some, but not all, island endemic white-eyes.)

These are the endemics, restricted to small ranges on their islands or archipelagos. Conversely, we also have a few ubiquitous white-eyes — the warbling-white eye, Swinhoe’s white-eye, and the silvereye — who’ve expanded across the Japanese Archipelago, Taiwan, the Philippines, Indonesia, and the Pacific Islands. It is these kinds of vast dispersions that can create isolated populations, and consequently lead to the formation of new species.

But how can the white-eyes be both accomplished travellers and sedentary species?

These apparently contradictory traits are partly responsible for the white-eyes’ reputation as “Great Speciators,”⁶ known for their ability to form new species at an extraordinary rate.

Just as our single human species (as well as other hominid species of the past) have been variably nomadic and sedentary, so too the white-eyes. Initially, there are bursts of dispersal, which favour those individuals who can travel to find new and potentially richer lands. This is followed by a “settling-down” phase once a suitable place is found, consequently reducing or cutting off gene flow to and from the settled population, resulting in isolation and the formation of new species. This history of dispersion-and-settlement, combined with other traits the white-eye’s possess, such as the ability to survive in varied habitats and relatively short generation times, has led to this great radiation of white-eyes across much of the world.

Although the causes of speciation are the same (dispersal followed by isolation), and the processes that cause the white-eyes to change are the same (natural selection and/or genetic drift), the results are different. The habit of island-hopping and speciating is common among the white-eyes, but each species that arises from this process is unique — some more so than others.

On the Northern Mariana Islands, located in the western Pacific over 1,000 kilometres south of the Bonin Islands, lives the golden white-eye, known for having plumage more radiant than any of its relatives. It shares a similarly confused taxonomic history as the Bonin white-eye (likewise thought to be a honeyeater) but now the two are considered one another’s closest relatives.⁷ How close is another question, for while they share a family, both are alone in their genera: the Bonin white-eye in Apalopteron, and the golden white-eye in Cleptornis. The “purpose” of a monotypic genus — that is, a genus containing only a single species — is to emphasis the uniqueness of a species, essentially saying: this species is so singular among its family that it cannot be closely grouped with any other.

The golden white-eye of the Northern Mariana Islands is the sole species in the genus Cleptornis. It’s also believed to be the closest relative of the Bonin white-eye.

There are thirteen genera within the white-eye family, five of which, including the two mentioned, are monotypic. These are the oldest speciations, the longest isolations. The remaining white-eye genera slowly increase in size — two species, three, four, five, seven — with the second-largest genus having just ten species. The ancestors of these genera split off from the rest of the white-eyes and each experienced their own small radiations (or splits, in the genera with just two species). And then there is the genus Zosterops, constituting the vast majority of white-eyes with over 100 species.

According to genetic studies, the Zosteropidae (white-eye) family first emerged 4.46 and 5.57 million years ago, and the Zosterops genus exploded into its great diversity in just the last 2 million years. Depending on the exact number of Zosterops species we count, this groups rate of spawning new species would be between 2.24 and 3.16 per million years. That’s an astonishingly fast rate of speciation for a bird lineage — the fastest ever recorded, in fact. And while many species radiations are limited to a single archipelago (anoles in the Caribbean, honeycreepers in Hawai’i, finches in the the Galapagos), the Zosterops radiation has extended from islands of the Pacific, to maritime and mainland East and South Asia, as well as most of Sub-Saharan Africa.

Several other groups of animals, including notably songbirds, present cases of radiation events. What’s special about the white-eyes is the speed and breadth of their radiation. Fast and far seems to be the motto of the Zosterops white-eyes.

Galápagos of the Orient

The Galápagos Islands, some 1,000 kilometres (600 mi) off the coast of Ecuador, are the poster child for evolution, and, more specifically, evolutionary radiation: with their famous finches (17 species from a single ancestor), lava lizards (10 species), mockingbirds (4 species), its iguanas (4 species), and giant tortoises (12 extant subspecies).

Similarly to the global white-eye radiation, insular radiation requires a balance of dispersal and isolation.

Across the 13 major islands of the Galápagos, and the 100+ smaller ones, the ancestors of these birds, lizards, and tortoises managed to disperse from island to island, yet they still found enough isolation to form distinct species (or subspecies) — in other words, traversal between islands needs to be easy enough for dispersion to occur, but not so easy that it occurs frequently enough to blend gene pools and prevent new species from forming.

The Bonin Islands have certainly been able to provide both ample isolation and time for change to occur, given that they began forming some 40–50 million years ago. The Bonin Islands have even been referred to as the “Galápagos of the Orient,” and while they may not have the same prestige or diversity of large fauna, they are more isolated and far older than the current Galápagos Islands, which only began forming over the last 3 to 5 million years.

Isolation and age breed a great diversity of endemic species: 40% of plants, around 25% of the 350+ insects, and 90% of the 100 recorded terrestrial snail species are endemic to the Bonin Islands.⁸ But size is also a factor. The Galápagos Islands span a land area of some 8,000 km² (3,000 mi²). The Bonin archipelago consists of a core collection of islands, arranged in groups from north to south as follows: the Muko-jima Group, Chichi-jima Group, and Haha-jima Group. These groups, along with some scattered islands and islets — the totality of the Bonin Islands — combine to form a land area of just 84 km² (32 mi²), smaller than the Galápagos by a whole two magnitudes.

Islands tend to reach a species equilibrium based on their isolation, size, and age.

The more isolated an island, the fewer new species arrive. The smaller the island, the more species go extinct. This means that, over time, small isolated islands tend to settle at an equilibrium of fewer species compared to larger, more connected islands, which can generally support a higher number of species. And, naturally, the smaller the islands, the fewer large species they can support — for, even if large land species like iguanas and giant tortoises did colonise the Bonin Islands, they would surely struggle to get by in such a small area, on such limited resources.

The Bonin islands — isolated, small, and ancient — have all the characteristics that would make for a fairly frugal fauna, but one rich in endemics (of the small kind). Today they host just one species of terrestrial mammal, the endemic Bonin flying fox, alongside the aforementioned menagerie of endemic snails, the handful of endemic insects, an endemic species of snake-eyed skink, and, of course, the Bonin white-eye; the only archipelago’s only endemic bird. But this wasn’t always so.

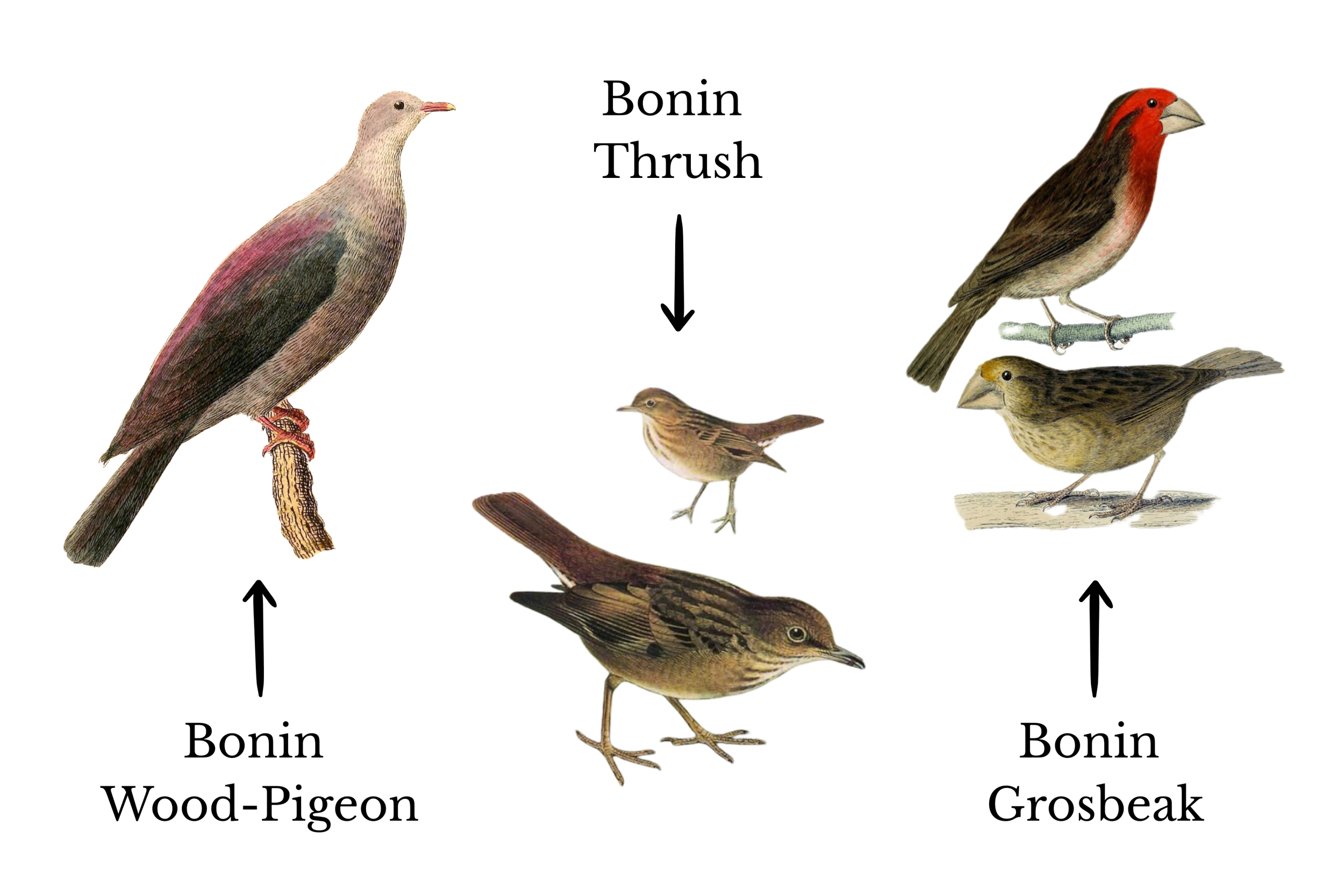

Among the first true explorations of the Bonin islands happened in 1827, when a Pacific expedition headed by British naval officer Frederick William Beechey anchored at Chichi-jima. There, they collected the specimens of two bird species: the Bonin wood-pigeon, dark-feathered and slick like an oilspill with iridescence, and the Bonin grosbeak, with a massive beak that claimed most of its facial real-estate. A year later, the Prussian explorer, naturalist, and artist Heinrich von Kittlitz, arrived on the same island to find (and later paint) the Bonin thrush, its brown plumage evocative of branches and tree bark.

At this time, the Bonin Islands were completely devoid of human settlements — their name is derived from the Japanese bunin (or munin), meaning "uninhabited" or "no people." However, during his stopover in 1827, Beechy picked up more than bird specimens; he also rescued two shipwrecked sailors. These castaways presumably took up the hobby of whale-watching to pass the time, for they recommended the Bonin Islands as a good spot for a whaling station. The first settlement of the islands began in 1830.

When the next exploratory expeditions arrived at Chichi-jima in 1853-4, the endemic thrush and grosbeak were not among the birds observed or collected. What the expedition did observe, however, were rats, cats, and dogs, feral sheep, pigs, and goats, as well as a much eroded landscape. The two endemic birds likely didn’t survive more than a decade post their discovery. The wood-pigeon survived for a bit longer on the Muko-jima group, where the last specimen was collected in 1889.⁹

In the past two centuries, the Bonin islands went from having four endemic birds to just one.

The extinct endemic aves of the Bonin Islands.

That last endemic, the Bonin white-eye, was once widespread across its namesake isles, meaning it was found across all three main groups. Why didn’t the Bonin white-eye radiate into three separate species, one for each of the major groups of the archipelago, like the finches or mockingbirds did on the isles of the Galápagos? It seems they were starting to, but the two subspecies that populated Chichi-jima and Muko-jima are no longer found there, likely meeting the same fate as the Bonin thrush, grosbeak, and wood-pigeon.

Today the Bonin white-eye is only present on Haha-jima and a few small adjacent islands, where it can be spotted in montane, valley, and lowlands forests, on plantations and in people’s gardens, near houses and inside roadside shrubs — almost any place that offers some cover from the sun and wind.

If you happen to visit Haha-jima, you’re chances of hearing this songbird sing aren’t great unless you yourself are an “early-bird,” for this white-eye only twitters its complex melody (“chew-i, chit-chit-pee, chot-chot-pee, ch-ee”) during the 20–30 minutes before sunrise. Instead, you’re more likely to hear the rise-and-fall trilling of its relative, the warbling white-eye.

This is a Zosterops white-eye, among those lighting-fast speciators, and one of the most widespread species of its family: covering much of East Asia, including Japan, Korea, and the Russian Far East, and down south across most of the Philippines and Indonesia. It is also a notorious island invader — most infamously on the Hawaiian Islands, where it was intentionally introduced in 1929 (in a bid to control insect pests), and has now become the most abundant land bird across the entire archipelago. And although the warbling white-eye, Z. japonicus, is native to much of Japan, it is not native to Bonin. Rather, it was introduced to the islands by humans between 1900–1910, and has since become quite common.

In 2001, BirdLife International released a publication chronicling the threatened birds of East Asia, wherein they reported that the warbling white-eye “occurs (apparently naturally) on both the Izu islands and Iwo (Volcano) islands, north and south of the Ogasawara [Bonin] islands, reinforcing the view that the Bonin bird is itself a white-eye since it would have replaced Z. japonicus on the Ogasawara islands.”

This shared evolutionary history, only uncovered in 1995, has consequences beyond the scholarly.

As would be expected from related species, the niche overlap between the Bonin and warbling white-eyes is significant: “a study on Haha-jima indeed showed the diet and habitat of the two white-eyes to be similar; although they separate in part by certain structural adaptations and foraging behaviour, with Bonin White-eye capable of more terrestrial foraging, both species feed on fruits, especially mulberries and papaya, leading to frequent supplanting attacks by one on the other, with no dominance hierarchy (Morioka and Sakane 1978).”

Often, the ranges of related species are partitioned with little to no overlap — i.e., there are few areas where they occur together. When a species invades the range of another closely related species (whether naturally or through human intervention), they’ll likely end up competing for the same niche. Ultimately, one or both of them will either have to adapt to a new niche or become more specialised in their existing niches. If that doesn’t happen, one species will end up outcompeting the other into extinction: “It is possible—even probable—that competition with the introduced Japanese [Warbling] White-eye has been a factor in the extinction of the Bonin White-eye on some of the smaller islands in its former range.” (BirdLife International, 2001)

The warbling white-eye was certainly not the only factor, however.

The introduction of rats and cats — speculated to have been a major driver in the extinction of the other Bonin endemic birds — likely had a hand (or clawed paw) to play in the extirpation of the Bonin white-eye from two of the three island groups. The Bonin white-eye is also reported to have “occurred in flocks large enough to be worth hunting for food” (Brazil 1991), and its taste for fruit may have led to its persecution as a crop pest. Finally, there’s the fact that much of the subtropical forests across the Bonin Islands have been cleared since settlement began in 1830 — “reduction of forest cover is the main threat to [the Bonin white-eye]” (Higuchi et al. 1980).

There are certainly plenty of imperiled white-eyes out there, most of them endemic to islands, many threatened by similar forces. These include the Vulnerable Seychelles white-eye, thought to have been extinct between 1935 and 1960 before its rediscovery; the Endangered teardrop white-eye, atop its single mountain peak, and the golden white-eye, Endangered by the looming risk of invasion by the rapacious brown tree snake;¹⁰ and Critically Endangered species like the Mauritius olive white-eye, its population in the low hundreds, and the Sangihe white-eye, living on an island stripped of forest, with a population estimated at under 50 mature individuals.

The Bonin white-eye is, surprisingly — given its history and current circumstances — not one of these threatened species. As of its last assessment in December of 2023, it is considered to be a species of Least Concern, its population stable, numbering around 15,600 mature individuals.

It’s not often we find an island species whose islands have been invaded by cats and rats, whose habitat has been greatly stripped back, who has been hunted and persecuted, extirpated from two-thirds of its home, and yet still seems to be doing relatively okay.

It’s hard to give a concrete answer as to how, but surely the Bonin white-eye’s adaptability — its generalist diet and ability to live in human-altered environments — has played a major role in its unprecedented survival. Perhaps it's not all that surprising. After all, the Bonin white-eye does come from a famously adaptable family and, in its isolation on Bonin, its evolutionary trajectory has taken it towards an even more generalist lifestyle. That’s not to say it’s invulnerable, of course. If things get bad enough, even the most adaptable of birds can break. A testament to that fact are Chichi-jima and Muko-jima, where you’ll no longer hear the Bonin white-eye’s morning song.

“This white-eye exists on one inhabited island, Hahajima, and its two small satellite islands. Although species used to occur in both the Mukojima and Chichijima island groups, the subspecies there is now extinct. Local extinctions have been attributed to a combination of habitat loss resulting from cultivation and predation by feral cats and introduced rats.” (Kawakami and Higuchi, 2013)

The ultimate question is: will the Bonin white-eye, the sole member of its entire genus, go extinct? Will it vanish now, having finally found its family after centuries of taxonomic debate? Will it leave the Bonin Islands bereft of their last avian endemic?

Just as the same series processes — dispersion, isolation, natural selection and genetic drift — lead to the formation of new, wildly different species, so too do the same set of destructive processes — invasive species, hunting, habitat alteration, etc. — cause the extinction of these unique creatures. These two great forces push against one another; one creating the other destroying. In our human-epoch, this Holocene, extinction certainly appears to be the dominant force.

Yet groups like the white-eyes still display an unmatched capacity for speciation. The warbling white-eye, distributed across its vast range of islands and archipelagos, has 15 recognised subspecies, any or all of which have the potential to form their own, full-fledged species.

Perhaps in some distant future, the Bonin Islands will be populated by several species of Apalopteron white-eyes; a radiation with the Bonin white-eye at its centre — descendants dispersing, settling, speciating. If any bird has the capacity, it is a white-eye.

¹ This number comes from a 2023 digital survey that more than doubled the previous estimate of Japan’s island count (6,852 islands counted in 1987). Many of these “newly discovered” islands would better be termed islets, as they are small and uninhabited — indeed, only a little over 400 of them host permanent human residents.

Taken at face value, this count would put Japan in eighth place, in terms of countries with the most islands, just behind the archipelago nation of Indonesia with its 17,508 islands (around 6,000 inhabited).

The most island-rich countries in the world?

Sweden, with over 267,000, followed by Norway (around 239,057) and Finland (around 179,000) — largely a result of their fragmented coastlines, with many of these islands (or rather islets) being pretty tiny.

² The family Leiothrichidae is commonly known as the laughingthrush family, but its 140+ species go by many names: laughingthrushes, sibias, liocichlas, minlas, and babblers. This etymological diversity is a reflection of their confused taxonomic history, being formerly grouped into the family Timaliidae along with many similar songbirds. This family served as a “wastebin taxon” for those birds of uncertain relation, and has since been split into the Sylviidae (which was also a wastebin taxon), Zosteropidae, Timaliidae (now much smaller), Pellorneidae, and Leiothrichidae — better aligned with true evolutionary relationships.

Today, the Leiothrichidae are distributed across the tropical forests of East, Southeast, and South Asia, as well as the grasslands and more arid regions of West Asia and Africa.

The family includes species like the southern pied-babbler, which forages in social flocks and has a strict system of sentinel duty. The silver-eared mesia, its gold-grey-red-black plumage appearing sown together in patches. And the Chinese hwamei (“painted eyebrow”), whose range has been greatly expanded due to its popularity as a cage bird.

³ “The reliance on tongue structure as a taxonomic character has led to erroneous classifications that have included honeyeaters, sunbirds (Nectariniidae, including Promerops), flowerpeckers (Dicaeum) and white-eyes in the same higher group, or to place them in sequence in a classification (Sibley and Ahlquist 1990: 612; 652-3; 665-675). Nectar-adapted tongues have evolved independently in other passerines, including leafbirds (Chloropsis), tanagers (Thraupini), Hawaiian honeycreepers (Fringillinae; Drepanidini), wood-swallows (Artamus), wood warblers (Parulini), troupials (Icterini) and some weaverbirds (Ploceinae). In some taxa there is only a tendency toward a nectar-adapted tongue, but it is clear that convergence has produced such tongues in several groups of distantly-related passerines.” (Springer, et al. 1995)

⁴ The founder effect is a fairly simple and intuitive concept: when a group of animals colonise a new land, the individuals in that group will only carry a fraction of their source population's genetic diversity.

Let’s say a group of songbirds belongs to a population where around 90% have white eye-ring and 10% have black eye-rings. A small group of these songbirds, let's say eight individuals, gets lost at sea and lands upon a far flung island. By random chance, 6 out of the 8 individuals happen to have black eye-rings. The island population will begin with that trait at an unusually high frequency, and, over time, it may become predominant or even fixed — not because it offers any advantage, but by the chance composition of the founder population and genetic drift.

And what is genetic drift?

Genetic drift is essentially evolution driven by chance rather than by adaptive advantage. This happens when individuals in a population just so happen to leave behind more descendants than others.

Let’s imagine a different scenario with our songbirds; where the eight individuals that arrive on the island are evenly split between white and black eye-rings. One of the white-rings is snatched by a snake, two pair up but fail to reproduce, another successfully breeds but only has one white-ring chick. The blacks-rings meanwhile, are all successful in rearing and raising their clutches. The crucial point is that none of these outcomes are related to eye-ring colour; it is simply misfortune and luck playing out in a small population. Now the population is skewed towards black eye-rings, and over several generations of such chance success and failure, the black eye-ring trait may become fixed in this population while the white eye-ring trait disappears — should this population speciate, the new species would then have solely black eye-rings.

Genetic drift is especially powerful in small populations, where the random loss or success of just a few individuals can dramatically reshape the population’s genetic composition.

⁵ “The diversity in the foraging ecology of Apalopteron is probably the result of niche expansion associated with the absence of tits, nuthatches, woodpeckers and small robins (Higuchi et al. 1995). The morphological differences between Apalopteron and Zosterops [typical white-eyes] may be correlated with the niche expansion of Apalopteron.”

⁶ Coined by biogeographer Jared Diamond in 1976.

⁷ The golden white-eye shares the North Mariana Islands with the Bridled white-eye (also endemic), and just north of this island group, exclusively on the small island of Rota, lives the Critically Endangered Rota white-eye.

⁸ The endemic invertebrates of the Bonin Islands include (to name a few) a species of waterstrider (Neogerris boninensis), a species of cicada (Streeyola boninensis), a species of jewel beetle (Chrysochroa holstii), a species of aquatic trumpet snail (Stenomelania boninensis), a species of amber snail (Boninosuccinea ogasawarae), and an entire genus of land snails (Mandarina), only found on these islands. See more here!

⁹ The Haha-jima group was also home to another endemic bat species (the Bonin, or Sturdee's pipistrelle) which, like the Bonin wood-pigeon, hasn’t been seen since 1889.

¹⁰ The island of Guam was once home to twelve endemic bird species from crows, to kingfishers, to honeyeaters, and even an endemic species of flightless rail.

Ten of those species are now gone from Guam, in large part due to an invasive brown tree snake that snuck its way onto the island (via a military cargo ship) and proceeded to dine on the local inhabitants and their eggs. Not only did the birdsong vanish, but the absence of forest birds led to the proliferation of spiders — with 40 times more spiders on Guam compared to neighbouring islands — the trees coated in thousands of their webs.

A single species turned a tropical paradise into a haunted island of spiders and snakes.

Where Does It Live?

⛰️ Most habitat types; from undisturbed forest to human-altered habitats.

📍 Hahajima Island and two satellite islands.

‘Least Concern’ as of 01 Dec, 2023.

-

Size // Small

Length // 12 - 14 cm (4.7 - 5.5 in)

Weight // 15 g (0.5 oz)

-

Activity: Diurnal ☀️

Lifestyle: Likely Social 👥

Lifespan: N/A

Diet: Omnivore

-

Class: Aves

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Zosteropidae

Genus: Apalopteron

Species: A. familiare

-

Among the white-eyes, of which there are over 100 species, the Bonin is unique for the dark triangles around its eyes. It is also unique in that it is the only species in its genus, Apalopteron.

Endemic to an archipelago some 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) south of Tokyo, the Bonin white-eye’s evolution — much like the evolution of many island species — is shaped by what its home lacks. In this case, many types of birds aren’t present on the Bonin Islands. As a result, the Bonin white-eye evolved into a generalist forager as it expanded to occupy niches normally split among species from several bird families.

This Bonin bird’s generalist habits resulted in a confused taxonomic history. When it was first described in 1831, it was initially placed into the bulbul family. Then it was moved into the Sylviidae family, then back to the bulbuls, briefly considered to maybe be a laughingthrush, and then a honeyeater, before finally — only in 1995 — being labelled a white-eye.

Once, the Bonin white-eye ranged across all three main island groups of the Bonin Islands, where it variously lived alongside an endemic wood-pigeon, grosbeak, and thrush. Today, these latter endemic species are extinct, and the white-eye can only be found on the Hahajima island group.

Surprisingly, the Bonin white-eye is neither Vulnerable nor Endangered, but a species of Least Concern according to the IUCN’s 2023 evaluation. How long it will remain that way is another question, given that the threats which wiped it out on the other islands — habitat loss, cats, and rats — are also present on Hahajima.

-

THE SYSTEMATIC POSITION OF THE BIRD GENUS APALOPTERON By H. G. Deignan

Singing Activity of the Bonin Islands Honeyeater (Passeriformes, Meliphagidae) by Tadashi Suzuki

Bird predation by domestic cats on Hahajima Island, Bonin Islands, Japan by Kamakami & Higuchi

Science Daily — Diversification of white-eyes

The Guardian — Diversification of white-eyes

Molecular Evidence That the Bonin Islands "Honeyeater" Is a White-eye by Springer, et al.

Distribution and Ecology of Birds of Japan by Higuchi, et al.

Threatened Birds of Asia: The BirdLife International Red Data Book

National Parks of Japan — Ogasawara National Park

Japan Travel — Okinoshima Island

Ogasawara World Heritage Centre

SPF: The Opri Center of Island Studies — Fauna of Bonin Islands

Birds of the World — Pycnonotidae

Birds of the World — Brown-eared bulbul

Birds of the World — Zosteropidae

Birds of the World — Sylviidae

Bird Guides — Sylviidae

Birds of the World — Meliphagidae

Birds of the World — Bonin wood-pigeon

Nature Picture Library — Extinct pigeons

Birds of the World — Bonin grosbeak

IUCN — Bonin grosbeak

What Is Missing? — Bonin grosbeak

Birds of the World — Bonin thrush

IUCN — Bonin pipistrelle

A Chronology of the Bonin Islands by Sebastian Dobson

THE HISTORY OF THE BONIN ISLANDS by Lionel Berners Cholmondeley, 1858-1945

Hawaii.gov — Warbling white-eye

BRAZIL, M. (2022). Japan: The natural history of an asian archipelago. Princeton University Press.

-