Nosy Hara Leaf Chameleon

Brookesia micra

The Nosy Hara leaf chameleon, endemic to a tiny Malagasy islet, is one of the smallest chameleons in the world and one of the smallest of all known amniotes (reptiles, birds and mammals). Its maximum length is no more than 3 centimetres (~1.2 in) — about the size of a paper clip.

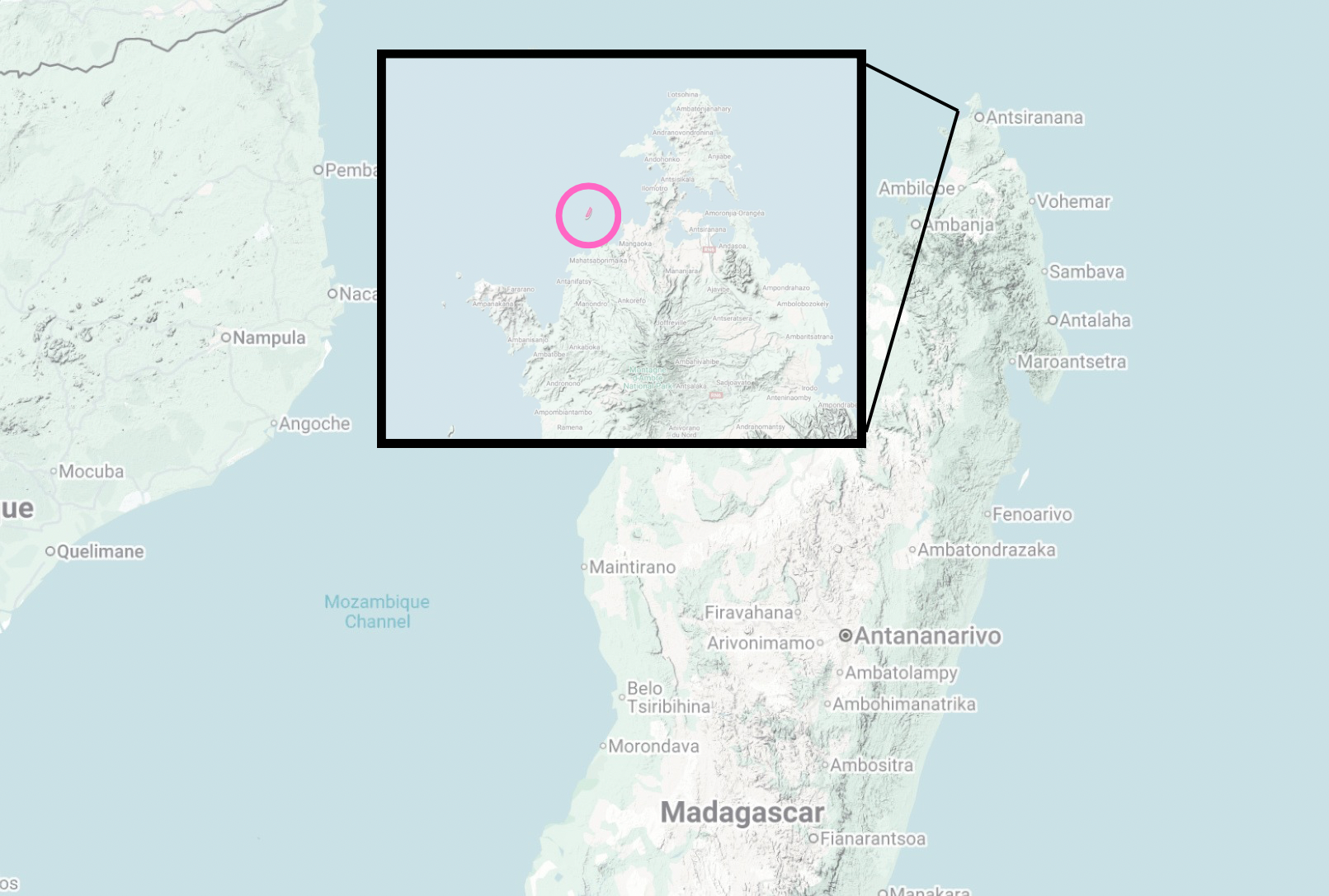

Just off the northwestern tip of Madagascar lies the tiny islet of Nosy Hara.

Shaped like a fat J, this speck of land is dominated by karst formations standing like ruined walls, crowded around with giant trees and bushes growing between the rock and forming the islet’s dry forest. No humans live here; for decades, Nosy Hara has been considered fady, or taboo. But, beneath the large bushes, in the cracks of the towering karst walls, and on the twigs of the giant trees, do live tiny chameleons.

Brookesia micra

Brookesia micra, the species is called, from the Greek word mikros. A micro chameleon.

Its absolute maximum length falls just short of 3 centimetres (~1.2 inches) — about the size of a paperclip.

How does an animal even get to be that small?

Surely, B. micra has been mistaken many times for the juvenile of some larger species of chameleon, and not just because of its size. Its dimensions, too, look downright infantile: its twiggy little legs look undergrown beneath its dumpy body, its orange tail — in most chameleons a long, dexterous fifth limb — is a stumpy down-curved thing, meanwhile its head is comparatively big and bulbous. Its frowning mouth and the droopy wrinkles around its manoeuvrable eyes, however, give this babyish chameleon the contradictory countenance of a curmudgeonly, tired old man.

“Its absolute maximum length falls just short of 3 centimetres (<1.1 inches) — about the size of a paperclip.”

These traits — big head, shorter tail and limbs, plus a simplified skeleton and genitals — are paedomorphic traits; that is, traits retained from its youth. In effect, B. micra reaches sexual maturity without completing full bodily development. This can happen in two ways: by slowing the rate of body growth (neoteny) or by accelerating sexual maturity (progenesis). Either mechanism preserves juvenile proportions into adulthood, allowing the chameleon to function as a fully mature animal while remaining extremely small.

And so we get a tiny chameleon, one of the smallest reptiles, and one of the world's smallest amniotes.¹ Indeed, many a bug is bigger than this lizard. On mainland Madagascar, hissing cockroaches grow to lengths of 10 centimetres (4 in), more than twice that of B. micra. The island of Nosy Hara alone is home to a cicada-killer wasps, arrow breasted scorpions, and a type of tarantula known as a baboon spider; all bigger, better armoured, and equipped with venomous weaponry. What kind of nightmare experience must B. micra live, surviving in a world of giant killer bugs.

Typical chameleons, such as panther chameleons, see insects as food; dining on crickets, beetles, and cockroaches. Unfortunately for B. micra, panther chameleons also live on Nosy Hara — ‘unfortunately’ because these larger chameleons, some 45 centimetres (18 in) long, also see smaller chameleons as food. As do birds, such as the Malagasy coucal, as well as frogs, snakes, and small mammalian hunters like tenrecs. B. micra has neither venom nor poison, it is not fast, nor especially smart.

It seems that this micro chameleon is at every disadvantage.

Why would an animal ever become so tiny?

Superiority of the Small

Is bigger always better or, in certain cases, is smaller superior?

The world’s largest chameleon species, Parson's chameleon, also hails from Madagascar. It measures up to 70 centimetres from the end of its prehensile tail to the tip of its protruding, rock-like nose — similar in size to an average house cat. It is certainly big, some 23 times bigger than B. micra, but it's far from invulnerable. If anything, it is even more vulnerable. Large and lumbering, with its scales often displaying a conspicuous canvas of colours, Parson's chameleon attracts the attention of large snakes and birds-of-prey like eagles, hawks, buzzards, owls, and banded kestrels.

One advantage of B. micra’s micro size is increased inconspicuousness.

Yes, it can be eaten by most any predator, but most predators won’t be able to find it.

Chameleons don’t primarily use their iconic colour-changing abilities for camouflage, as the popular myth states, instead shifting hues to communicate and regulate body temperature.² B. micra, however, barely changes colour at all. Known as a “leaf chameleon,” it spends its day wandering about in the leaf-litter, and so it simply maintains an unflashy colouration of browns and oranges that matches its surroundings. At night, it climbs foliage to sleep among the protruding roots and branches — scaling “great” heights, up to 10 centimetres (4 in) off the ground. Grasping a twig with its own twiggy limbs, it sways back and forth subtly, like a leaf stirred by wind.

Larger chameleon species similarly rock in the breeze in order to make themselves more cryptic; staying otherwise motionless, except for their turret eyes that swivel independently, nervous-looking, scanning for dangers. If spotted, they have few options for defence. If they’re large enough, they’ll likely opt for intimidation; scrunching their bodies together, inflating their lungs and air sacs (hollow, finger-shaped projectile at the edges of their lungs) to make themselves appear larger from the side (and like thin disks from the front), puffing and hissing and opening their mouths.

B. micra isn’t intimidating any predators. Instead, it has its own suite of unique defensive behaviours.

One is the freeze, drop, and roll. If a leaf chameleon feels that it’s in imminent danger, it tucks its legs in towards its body, drops off its branch to the ground — protected from impact by its light weight — and rolls away like a tiny log. If the predator somehow continues its pursuit, B. micra can try again for camouflage. Instead of compacting its body to appear more intimidating, as other chameleons might, it flattens itself to appear more leaf-life. But say that an extremely discerning predator still manages to find this miniscule, leaf-like, camouflaged chameleon, somehow, and takes it into its mouth. It seems B. micra is doomed.

Then it begins to vibrate. Its entire body buzzes, and the predator feels as if it ate a live bee. With this unusual sensation in its mouth, the predator spits out its snack. B. micra employs its final trick: a feigned death — more technically known as akinesis (“without motion”) or thanatosis (“death-state”). B. micra once again goes completely motionless, pulling its limbs tight towards its body, and possibly even sticks out its hyoid — akin to the cartoony tongue-out death expression. By all visual metrics, it appears dead. Once the predator loses interest, B. micra miraculously "resurrects" and waddles away.

Dwarfism

Aside from improved invisibility, does small size offer any other benefits? Would a larger species ever benefit from shrinking, and in what situations would that happen?

Smaller areas have limited resources. The fewer the resources, the harder it is to obtain enough to grow to great size. And what kind of environments, generally, have small areas and limited resources?

Continental Africa spans an area of 30.37 million km². The second largest continent on Earth.

Madagascar covers an area of 587,041 km². The fourth largest island in the world.

The islet of Nosy Hara has an area of some 3 km².

A species is newly stranded on a small island; say it was washed from Madagascar to Nosy Hara on a raft of vegetation. The species reproduces and, each generation, the offspring compete amongst each other. Those born big starve, unable to find the same volume of resources their ancestors found on the much larger Madagascar. Those born smaller can subsist on what’s available, surviving to reproduce, and passing on their smaller size to their offspring.

Another way to frame it is through the economy of supply and demand. Initially, reproduction will be rapid, as the species fills out uncontested space on its new island home. This is the boom. But supply is limited and eventually it runs low, outpaced by increasing demand. Then comes the bust. There is starvation and death for some — the large bodied, those that need the most resources to survive. But others, the small-bodied that can get by on less, make it through this bottleneck to see the supply replenished as demand (the total population) falls. And the small go on to give rise to more small offspring.

Either way you look at it, the result is the same. Over time, the stranded species shrinks.

-

Food availability, then, is important. Let’s look at an example of two mostly carnivorous species.

The island fox, Urocyon littoralis, is endemic to six of the Channel Islands off the coast of California. It is a descendant of the mainland grey fox, Urocyon cinereoargenteus, which often preys on rodents and rabbits. The diet of the island fox, however, consists of small fare like deer mice, ground-nesting birds, lizards, and lots of insects. The island fox is also 25% smaller than the mainland grey; its body size has decreased to align with insular resource availability.

A contrasting case is that of the Falkland Islands wolf, a recently extinct (1876) canid from a remote archipelago in the South Atlantic. At first it seems to refute the pattern: it maintained the same body size as its mainland ancestral species.³ But it seems its diet of larger prey was maintained too, given the complete lack of small mammals on its islands. The Falkland Island wolf, then, remained large to continue hunting large prey.

In summation, “carnivore size on islands is closely related to the relative abundance and size spectrum of available resources” (Meiri et al., 2006) — with an additional clarification. It seems that carnivores will still shrink even if large prey is available on their island, as long as small prey is also available. However, if only larger prey is available, as on the Falkland Islands, carnivorous species seem to retain their size.

But food limitation is just one driver of dwarfism on islands — with the size and availability of prey especially affecting carnivore body size. The other major drivers are competition and predation, or the lack of them.

-

During the Pleistocene epoch, spanning 2.5 million to 11,700 years ago, several species of deer and elephants inhabited the islands of the Mediterranean.

One such was a dwarf elephant, Palaeoloxodon falconeri, that lived on the island of Sicily from at least 500,000 years ago (and likely went extinct around 200,000 years ago). Descended from the straight-tusked elephant, Palaeoloxodon antiquus, of Europe and western Asia, this dwarf species shrank to under 1 metre (3.3 ft) at the shoulder — the smallest of all dwarf elephants — roughly 23% the size of its mainland ancestor. What caused it to become so small?

The mainland was home to predators like cave lions and hyenas (both larger than their modern counterparts), and so, for herbivores, large size came in useful as protection against predation. There were also other large herbivores around, and, when there is competition for the same resources, it is often the larger party that is successful in laying down their claim.

The island of Sicily didn’t have any large predators to threaten the elephant, nor were there any other large herbivores to compete with. Without predation and competition, the selection pressure for large body size decreased, and P. falconeri was free to shrink. The only remaining pressure was resource limitation, so small size became advantageous.

Then there are the ancient deer from the island of Crete. This island was home to several species, possibly more than six, and although there were no large predators on Crete, competition between species seemed enough of a driving force for two of the species — Candiacervus major and C. dorothensis — to maintain the size, or grow even larger, than their mainland counterparts (Raia, 2006).⁴

So does competition lead to smaller or larger island species?

Earlier we saw that competition for limited resources led to smaller size on islands, since smaller individuals could better survive on less food. This is true in some cases, yes. If resources are scarce and patchy, individuals with smaller bodies, needing less food, can survive on less or lower-quality forage, and reproduce even in lean times. Their smaller size may even increase their rate of reproduction, as smaller size typically comes with shorter gestation periods and generation times. The Key deer, for instance — endemic to the Florida Keys where food is limited and patchy — has shrunk to become the smallest subspecies of white-tailed deer.

In other cases, however, it pays to be larger. If the limiting factor is access to higher-quality food due to competition with conspecifics, then bigger individuals may dominate feeding sites, pushing smaller ones aside. And if competition is between individuals of different species, some may be forced into niches that require larger size — allowing them to access higher vegetation, for instance.

While the body size of carnivores seems to be determined predominantly by the size and availability of prey resources, herbivore body size is determined by predation and even more so by competition. Size evolves towards an energetic optimum that balances energy intake (the amount of resources available), energy demand (body size), and competitive advantage (how much does it pay to be big). If it pays little, then there will be a trend towards shrinkage, if it pays a lot, size will be maintained or even gained

This concept, species becoming smaller on islands, is known as insular dwarfism. It is part of a larger concept known as the island rule or effect. “Effect” is the better descriptor here, for the “rules” of the island rule aren’t universal, nor predictable, and they have plenty of exceptions. The other key concept encompassed by the island effect is island gigantism. This is the process of species getting bigger on islands — the inverse of insular dwarfism.

Island gigantism has crafted the coconut crab, which, dispersing across the islands of the Indo-Pacific, grew be 1 metre (40 inches) long from one leg tip to another. On prehistoric Madagascar it gave us the elephant birds, the heaviest birds to ever live at over 500 kilograms (1,100 lb). And it gave us the giant gecko of New Caledonia that can grow to over 40 centimetres (16 in) long, its detachable tail alone as big as a regular gecko.

In a phrase, the island effect highlights that weird things happen to body sizes on islands.

Miniature, Micro, & Nano

Is B. micra, the Nosy Hara leaf chameleon, a case of insular dwarfism?

It seems to fit the picture: an unusually small species isolated on a tiny islet. Indeed, the paper (Glaw et al., 2012) that first described the species in 2012 concluded that “with a distribution limited to a very small islet, this species may represent an extreme case of island dwarfism.” But some new discoveries have complicated things. One major discovery was that of a new miniature chameleon.

B. micra belongs to genus Brookesia, the leaf chameleons of Madagascar, of which there are over 30 known species. One of the latest additions, described in 2021, is Brookesia nana, its specific name derived from “nano.” It is the nano chameleon; one magnitude down in scale from “micro,” and, indeed, B. nana turned out to be even smaller — by a millimetre or so, in max size — than B. micra. It turned out to be the smallest known species of reptile on the planet.

“One of the latest additions, described in 2021, is Brookesia nana, its specific name derived from “nano.” It is the nano chameleon; one magnitude down in scale from “micro,” and, indeed, B. nana turned out to be even smaller — by a millimetre or so, in max size — than B. micra. It turned out to be the smallest known species of reptile on the planet.”

The thing is, B. nana doesn’t live on some tiny islet. It lives on Madagascar proper, in the montane rainforests of the northern tip. Its size, then, doesn’t seem to be a result of insular dwarfism.

All 30+ species of Brookesia are small, as far as chameleons go, with the largest, the Antsingy leaf chameleon (Brookesia perarmata), still measuring just 11 centimetres (4.3 in) long at most. And most of the leaf chameleons, like B. nana, live on mainland Madagascar. Of course, Madagascar is itself an island, but given its massive size — sometimes called the “Eighth Continent” — the island effect appears to have less influence on its fauna.

-

Do larger islands exert a weaker island effect?

The larger the island, the more similar the conditions — the amount of resources, size of habitats, complexity of ecosystems — are to the continents. As a result, these differences (which drive insular dwarfism or gigantism) would be lessened. But even on some of the largest islands, like Madagascar, they aren’t completely absent.

The Malagasy giant rat looks more like a rabbit than a typical rat, and — while it is a rodent — it is also closer to rabbit-sized: weighing 1.2 kilograms (2.6 lb). Perhaps a lack of predators (or at least relative decrease in predation compared to mainland Africa) allowed the species to grow, since it no longer needed its small size as much to hide from them. Compare it to its relative, the white-tailed rat of South Africa, which weighs just 60–100 grams (2–3.5 oz).

An opposite case are the Malagasy pygmy hippos, three species that lived on the island until their extinction around 1,000 years ago. Although they were believed to be close relatives of the common hippo — which can grow to be as large as 3.5 metres (11.5 ft) long and 1.7 m (5.6 ft) tall — these island hippos were significantly shrunken, with one of the species, Hippopotamus lemerlei, only reaching a max size of 2 metres (6.5 ft) long and 0.76 m (2.5 ft) tall. A release from competition pressure with other large herbivores, plus the limitation of resources on the island, likely caused this dwarfism.

Other examples of dwarfism on Madagascar include Madame Berthe's mouse lemur, the smallest primate in the world, weighing just 33 grams (1.2 oz) — lighter than a golf ball; the yellow-bellied sunbird-asity, a bright yellow and metallic-blue bird measuring just 10 centimetres (4 in) in length; and the Mini mum, a frog species about 1 cm (0.4 in) long.

The island effect does seem to be present on large islands, just lessened in strength as compared to smaller islands. For example, Frances's sparrowhawk (Tachyspiza francesiae), with its wingspan of around 47 cm (18.5 in), is a small raptor relative to its continental relatives — the brown goshawk (Tachyspiza fasciata) of Australia has a wingspan of around 85 cm (33.5 in). Frances's sparrowhawk can be found on Madagascar and the nearby Comoros Islands. Divided into several subspecies, those from the much smaller Comoros — such as the Anjouan sparrowhawk, from the 424 km² Anjouan island — are substantially smaller than the Madagascar subspecies.

This drive towards dwarfism is shared by the entire genus Brookesia, not just those found on small islands. What we’re seeing is a genus-wide trend towards miniaturisation.

Prior to the discovery of B. micra on Nosy Hara in 2012, the smallest known lizard was another Brookesia species: B. minima.⁵ That species is commonly known as the Nosy Be leaf chameleon, after the island to which it is endemic. So, two of the world's smallest known lizards arose on islands. Perhaps all Brookesia chameleons were trending towards small-size — under Madagascar’s weaker island effect, or for other adaptive reasons — while minima and micra, under their stronger island effect, became even smaller. But what of B. nana then? How come it’s even smaller than its small island relatives?

“Prior to the discovery of B. micra on Nosy Hara in 2012, the smallest known lizard was another Brookesia species: B. minima. That species is commonly known as the Nosy Be leaf chameleon, after the island to which it is endemic.”

Why would small size evolve in a mainland species? After all, tiny species don’t only live on islands: from the 1–2 cm (<1 in) pumpkin toadlets of Brazil’s Atlantic Forest, to the 4 cm (1.6 in) dwarf catfish of northeastern India and Bangladesh, and the 3 cm (1 in) bumblebee bat from the limestone caves of western Thailand and southeastern Myanmar.

One advantage we’ve already seen is improved crypticity; the smaller you are, the harder you are to spot. Heavy predation pressure can drive miniaturisation, as the largest individuals are spotted and eaten while the smaller ones get away to have offspring. Or maybe a dwarf species, by becoming smaller, is able to escape competition by shrinking into a new niche; for instance, instead of competing with larger chameleons for the same insects, the tiny chameleons can specialise exclusively in tiny prey.

What this niche specialisation can often lead to, however, is restriction to a micro-habitat.

That is, a species shrinks, specialises, and shrinks, and so on, until it can only really survive in a specific type of habitat — often one that is patchily distributed across a larger habitat. B. nana is found only in a single patch of montane rainforest on the Sorata massif of northern Madagascar. Like other Brookesia, it is a leaf-litter microhabitat specialist, dependent on the forest floor’s moisture and cover — its tiny size and cryptic behaviour make it highly adapted to that niche of shaded, humid, low-lying forest detritus. Given that it’s only known from one specific location, it's fair to say that its range is extremely limited, likely less than a few square kilometres.

A small livable space surrounded by a sea of inhospitable environment — sound familiar?

It’s possible that B. nana’s micro-habitat acts somewhat like an island; imparting the same island effects without being an actual island. Indeed, the biogeographical definition of island is broader than the standard one, encompassing not just a landmass surrounded by water but any isolated and suitable habitat surrounded by inhospitable conditions. These are so-called ecological islands: oases in the desert, green parks in city landscapes, alpine forests on mountain tops, and even lakes surrounded by land. And what may be an ecological island to one species, may not be to another. A landscape of forest fragments surrounded by farmland may serve as one big hunting territory for a generalist species like a fox, while for another species, such a tree-dependent flying squirrel, the forest fragments would be islands in a farmland sea.

Perhaps the entire genus of Brookesia chameleons initially shrunk to escape predation pressure or competition with the larger chameleons of Madagascar. At some point, B. minima and B. micra became isolated from the mainland — likely when sea levels rose and turned Nosy Be and Nosy Hara into islands — whereupon they were subjected to a strong island effect, causing them to shrink even smaller. Back on mainland Madagascar, meanwhile, B. nana was adapting to a particular niche within a particular micro-habitat. No longer able to survive outside of that niche, B. nana’s micro-habitat became an ecological island, simulating insular conditions, exerting on the species the same pressures as if it were isolated on an actual island. And so B. nana shrunk to become smaller than all its relatives, and any other known reptile on the planet.

That’s a plausible explanation, but given the lack of fossilized Brookesia ancestors, "plausible" is all it can be for now.

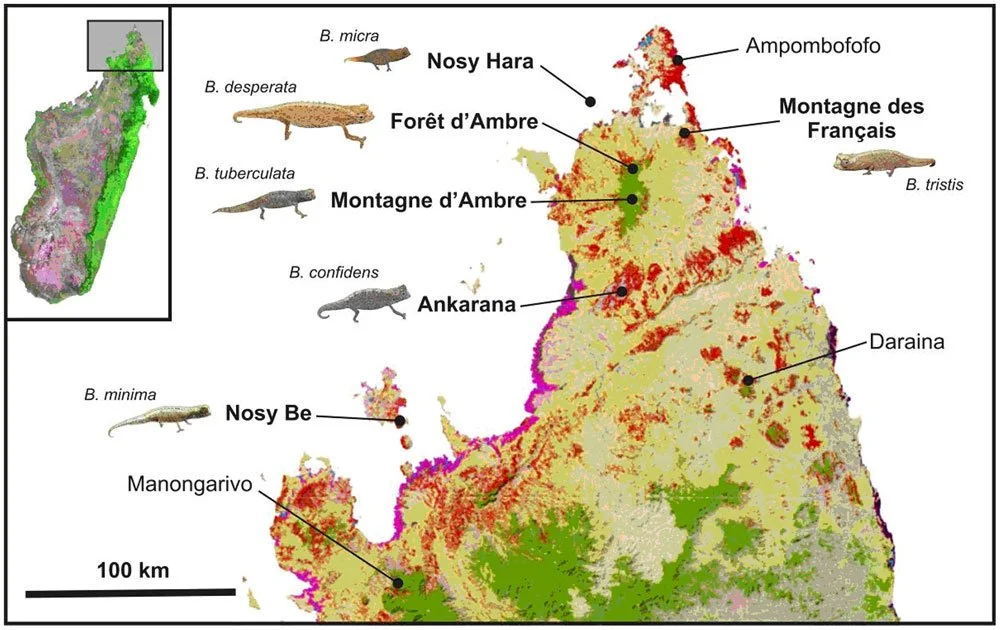

“Map of northern Madagascar showing distribution of species of the Brookesia minima group.” (B. nana was yet to be discovered.)

Whether or not their small size is truly (or fully) caused by the island effect, the smallest of the Brookesia — the miniature, micro, and nano chameleons — are at least interesting case studies of insular dwarfism. What appeared to be obvious instances of insular dwarfism in B. minima and micra, turned out to be more complicated. Meanwhile, B. nana’s nano size could be a result of insular dwarfism, of the island effect, if an unusual case on an atypical “island.”

These are not clear-cut cases of insular dwarfism. But neither is the island effect a straightforward, clear-cut rule. It is, rather, a pattern we’ve noticed and tried to make sense of. After all, the two main paths of the island effect are exact opposites — shrink or grow — and a species may be driven to one or the other for the exact same reason (such as the need to escape competition).

Insular dwarfism is a real process that happens. Its drivers — those features of islands that cause species to shrink — are many. They affect different species differently, depending on their traits; herbivore or carnivore, reptile, mammal, insect or bird. And they change depending on the ecology of the island (are there many predators present, is there heavy competition for particular niches?) as well as the island’s geography (is it big or small, what habitats does it feature?). The drivers of insular dwarfism can also overlap with the pressures that cause miniaturisation in mainland species, and, at the same time, mainland species may be subject to a kind of “ecological island effect.”

The island effect can be summed up in a single broad definition: island populations of animals change in size. Look for a deeper explanation and you’ll find a tangled web of cause and effect between a species’ traits and evolutionary history, and the geography and ecology of its island. The island effect can be subtle, even cryptic, and far more complicated than it appears at first glance, as exemplified by the tiny Brookesia chameleons.

¹ Amniotes are a group of animals defined by the presence of a membrane that surrounds the embryo during development, called the amnion. The amniotes are mammals, birds, and reptiles.

² Since chameleons are ectothermic, relying mostly on external heat to keep their bodies warm, they need to sunbathe. If you’ve gone outside on a hot, sunny day in black clothes, you’ll know that an effective way to absorb more of the sun's heat is to be darkly dressed. Instead of dressing up, a chameleon simply changes the colour of its scales to a darker hue.

³ The mainland counterpart to the Falkland Islands wolf (in the same genus) is Dusicyon avus, living in South America from around 780,000 years ago and going extinct perhaps 400 years ago. It’s estimated to have weighed 10–15 kg (22–33 lb), compared to the Falkland Islands wolf which weighed around 20 kg (44 lb).

⁴ “Candiacervus major, the largest among the endemic deer species recorded in the Pleistocene‐Early Holocene of Crete” (Palombo & Zedda, 2022), may actually be a case of pituitary gigantism — a condition where the pituitary gland releases an excess of growth hormone, causing abnormal size — as suggested by several anatomical traits (“a reduction in cortical bone thickness and the presence of wide lacunae inside of the bone tissue… extremely elongated distal part of the metatarsal diaphysis, the proportionally small proximal epiphysis, and some bone gracility”).

These findings may put this rare case of mammalian island gigantism into question.

⁵ Brookesia minima was discovered in 1893 → B. micra in 2012 → B. nana in 2021. If this progression of discovery, of the world's smallest lizards, were to continue, we might soon expect to find a Brookesia pico.

Where Does It Live?

⛰️ The floor of dry forests, usually in leaf litter.

📍 The island of Nosy Hara, off the northwestern tip of Madagascar.

‘Near Threatened’ as of 12 Aug, 2014.

-

Size // Tiny

Length // 29–30 mm (1.1–1.2 in)

Weight // N/A

-

Activity: Diurnal ☀️

Lifestyle: Solitary 👤

Lifespan: Up to 10 years in captivity (reportedly)

Diet: Carnivore (Insectivore)

Favorite Food: Tiny insects 🦟

-

Class: Reptilia

Order: Squamata

Family: Chamaeleonidae

Genus: Brookesia

Species: B. micra

-

Brookesia micra, also known as the Nosy Hara leaf chameleon, is only found on a tiny islet of the same name off the northwestern tip of Madagascar. The “leaf” in its name refers to its preferred habitat: the leaf litter on its islet’s dry forest floor.

At a maximum length of less than 3 centimetres (~1.2 inches), B. micra was, upon its discovery, not only the smallest chameleon species, not just the smallest reptile, but the smallest of all amniotes (reptiles, birds, and mammals).

Its top spot — on the tiniest of podiums — was stolen in 2021 when another chameleon, Brookesia nana, was discovered in the montane rainforests of northern Madagascar. It was found to be smaller by a millimetre or so.

When B. micra was discovered in 2012, it was believed to be a particularly extreme example of a phenomenon known as ‘insular dwarfism,’ wherein certain species, stranded on islands, tend to shrink in body size. However, the discovery of the even-smaller B. nana appeared to refute that idea, for it evolved its extreme smallness on the much larger island of Madagascar.

B. nana is found only on a single massif, and only in a single patch of montane rainforest. Like other Brookesia, it is a leaf-litter microhabitat specialist, filling a very particular niche. Only known from one specific location, B. nana’s range is extremely limited, likely less than a few square kilometres.

A small livable space surrounded by a sea of inhospitable environment — sound familiar?

It’s possible that B. nana’s micro-habitat acts somewhat like an island — an ‘ecological island’ — imparting the same island effects without actually being a true island, and causing B. nana to shrink into a nano chameleon.

-

iNaturalist — Nosy Hara observations

Mongabay — Dwarf lemur on Nosy Hara

Mongabay — Discovery of Brookesia nana

Encyclopaedia Britannica — Chameleons

Body size of insular carnivores: Evidence from the fossil record by George A Lyra, et al.

THE ISLAND RULE IN LARGE MAMMALS: PALEONTOLOGY MEETS ECOLOGY by Pasquale Raia and Shai Meiri

National Park Service — Island fox

Animal Diversity Web — Grey fox

Birds of the World — France’s sparrowhawk

Birds of the World — Brown goshawk

-