Cuckoo-Roller

Leptosomus discolor

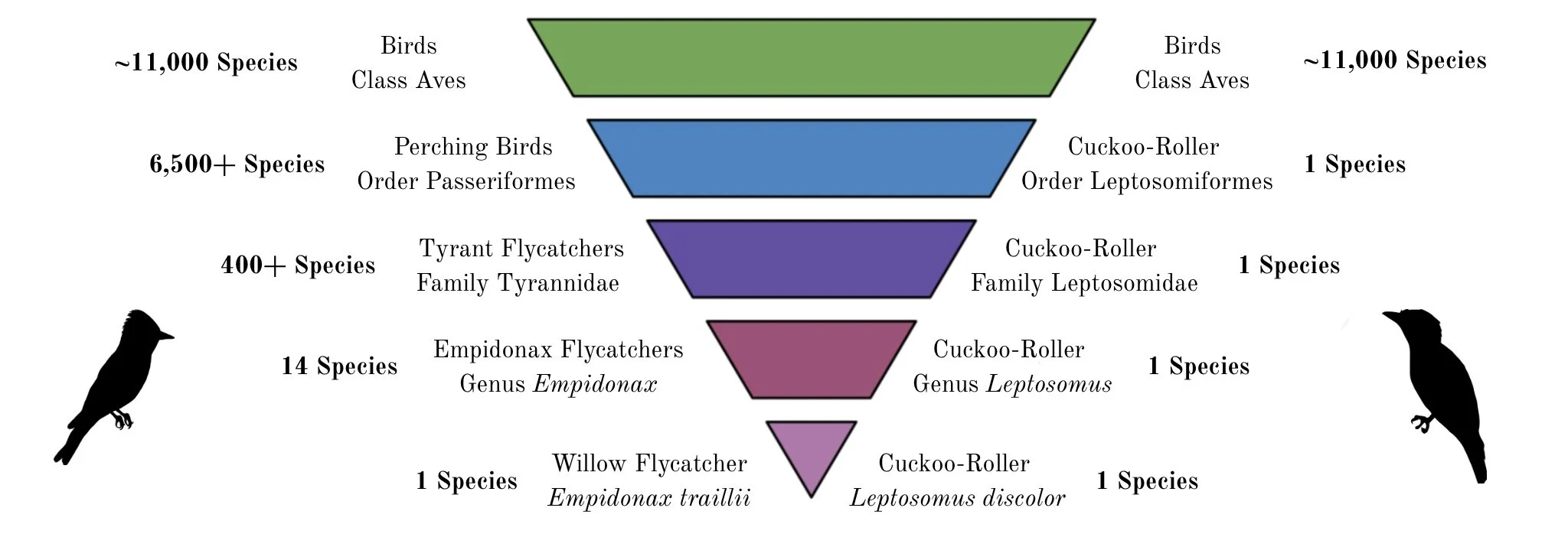

The cuckoo-roller is a relic species: the sole living member of the order Leptosomiformes — for comparison, other bird orders can contain hundreds of species, while Passeriformes (a.k.a. songbirds) has over 6,500. And, despite its name, the cuckoo-roller is not closely related to cuckoos nor rollers.

Relics

What is a relic?

An artefact of history. A leftover piece of a long-gone past. Something of significance: to be protected, delicate, and treasured, one-of-a-kind. A relic is not solely defined by its own qualities, but what has been lost around it. And the term doesn’t just apply to an ancient sword or statue, or the withered body-part of some renowned saint. A relic can be living.

Organisms can become relict in a couple of ways.

A once-widespread population or species is restricted to a far smaller range than the one it used to occupy.

The Sumatran tiger, a subspecies, was isolated as the last ice age came to an end and sea levels rose, turning Sumatra into an island; the other island subspecies (Javan and Bali) then went extinct, and the Sumatran tiger was relict. As glaciers retreated from southeastern Norway, they created lakes where cold-water shrimp like Mysis relicta are now isolated as glacial relics. Once found across Nevada, Utah, and northwestern Arizona, the relict leopard frog now survives only in a few Nevada waterways, reduced — by habitat loss, urbanisation, and invasive bullfrogs — to a human-made relict.

The Sumatran tiger, Mysis relicta, and the relict leopard frog, confined to tiny fragments of space, are relics of what they once were. More specifically, they are geographical relics; created by changes in climate, geological forces, or anthropogenic upheaval of habitat.

But there is another kind of living relic.

An organism that is relict in time, rather than space, defined by the relatives that perished around it — a relic by virtue of its persistence. This kind of organism, known as a relictual species, is the sole surviving representative of a once diverse group.

Cuckoo + Roller

The name cuckoo-roller slap-dashes together two quite different types of birds.

The cuckoos belong to the order Cuculiformes, which comprises some 150 species, and is most famous for its brood parasites.¹ The rollers, meanwhile, are 13 species that make up the family Coraciidae (family being one rung under order on the taxonomic ladder), and are known for their aerial acrobatics.

The cuckoo-roller was given its chimeric name by early naturalists who couldn’t figure out what it was, and so they applied birds they did know in order to make sense of the creature: it has a long tail, a slightly curved bill, and a somewhat cuckoo-like silhouette in flight, but it also has a broad head, coloured wings, and a rolling or tumbling flight-style reminiscent of rollers.

The cuckoo-roller is slightly larger than most cuckoos or rollers, measuring some 45 centimetres (18 in) long, with its most distinctive feature being its big, broad head. Its most stylish feature depends on sex, for the cuckoo-roller is sexually dichromatic (varying in colour). The female has a brown back, wings and tail feathers, but a creamy face, chest, and underbelly, covered in dark brown spots that become more concentrated near her head. The male, meanwhile, has plain grey underparts but iridescent wings, and around his eyes — placed oddly high on the head — he has black streaks that bring to mind the makeup of a mime.

The cuckoo-roller is traditionally a bird of the forests and woodlands, but it also ventures far into tree plantations, parklands, and cultivated fields — not unlike many species of rollers — and it's known to be quite tolerant of humans. The cuckoo-roller's feet are small and, like those of some cuckoos, zygodactyl; two toes point forward and two point back. Unlike cuckoos, but similar to rollers, the cuckoo-roller is a cavity nester, laying its eggs inside tree hollows up to 1·2 metres (3.9 ft) deep (its even been observed sharing its nest with other birds, including, on one occasion, a broad-billed roller). And, like both cuckoos and rollers, the cuckoo-roller is primarily carnivorous: taking invertebrates like locusts, mantises, and cockroaches, as well as reptiles like geckos and small chameleons.²

But here’s the thing: the cuckoo-roller is not closely related to cuckoos nor rollers.

Its name — composed of two other birds — is somewhat ironic, given that the cuckoo-roller is a relict species; by definition, quite unlike any other living bird.

Taxa: Large & Small

Let us get some perspective.

As far as taxonomic orders and families go, the cuckoos and the rollers aren’t especially impressive.

The largest bird order, the Passeriformes (the perching or songbirds), consists of over 6,500 species. Those species are divided into around 140 families — compared to the Cuculiformes (cuckoos), with just one family — the largest of which, the Tyrannidae family (tyrant flycatchers), has over 400 species. Indeed, a single genus within that family, Hemitriccus (bamboo tyrants), contains 22 species. The roller family, with just 13 species, looks pretty meagre by comparison.

But the cuckoos and rollers are crowded dynasties compared to the cuckoo-roller.

The cuckoo-roller is the sole species in its genus, Leptosomus.

This isn’t too uncommon: many of the tyrant flycatcher species — the sulphury flycatcher, long-tailed tyrant, boat-billed flycatcher³ — are also species alone in their genera (in other words, they belong to monotypic genera).⁴ This designation simply means that, among such a large family, these species were distinct enough from their relatives to be placed in their own low-level group; their own genus. But whereas the tyrant flycatchers unite to make a family of 400 plus, the cuckoo-roller is also the sole species in its entire family, Leptosomidae.⁵

This is more rare. A bird, or any animal, would have to be truly quite special to be placed alone in an entire family. Still, there are plenty of examples: the Egyptian plover, a wading bird famous for its crocodile “dentistry” work, is alone in the family Pluvianidae; the secretarybird, strutting across the African savannah and striking at snakes with its lengthy legs, is alone in the family Sagittariidae; the blue-capped ifrit, a resident of New Guinea’s rainforests and one of the few known toxic birds, is alone in the family Ifritidae. If you were looking for odd and one-of-a-kind species, these families-of-one are where you’ll find them.

Above family is order. Here you get broad groupings like the Anseriformes (the waterfowl, 170 species, including all ducks, geese, and swans), the Accipitriformes (diurnal birds of prey, 250 species of eagles, hawks, kites, harriers and vultures), and the Charadriiformes (the shorebirds, 390 species, encompassing seagulls and terns, sandpipers and stilts, plovers and lapwings, puffins and auks, jacanas, skuas, buttonquails, etcetera) — as well as the previously mentioned Passeriformes; with some 6,500 species, ranging from crows to swallows, finches to fantails, starlings, sparrows and tits, sunbirds and shrikes, oxpeckers and treecreepers, fairy-wrens, birds-of-paradise…the list goes on.

The order Leptosomiformes has one species: the cuckoo-roller.

Above order is class — the class Aves, for instance, encompassing all of the birds.

The cuckoo-roller is as unique a bird as can exist.

Isolation & Uniqueness

There are few places more conducive to spawning unique species than islands, and, fittingly, the cuckoo-roller is found only on Madagascar and the nearby Comoro Islands. Isolation breeds innovation, or at least variation.

Of course, islands are all different — with different climates, habitats, ecologies, and histories — and you’ll be hard pressed to find islands with so different a history as the two homes of the cuckoo-roller.

Madagascar, or at least the rock it's made of, has existed as long as the world has had continents. Indeed, it was once a part of one; some 165 million years ago the supercontinent of Gondwana began to break up, and Madagascar, then conjoined with India, made its split from Africa. Later, between 80–90 million years ago, India broke off to embark on its collision course with Asia. Madagascar was isolated, made into an island.

The Comoros Islands were not abandoned at sea, as Madagascar was, but were instead birthed from it. These are volcanic isles: created as magma spewed from the ocean floor, rising as volcanoes above the ocean surface, eventually forming into four islands. And they are young, even as volcanic islands go. The oldest, Mayotte, is 7-8 million years old, while the youngest, Grande Comore — still volcanically active — is less than a million years old.

One is a continental island, broken off from the mainland, ancient, some 80 million years old, and massive, the second-largest island in the world today. The other is a volcanic archipelago risen from the sea, young, less than 8 million years old, and composed of several small isles (the largest, Grande Comore, is around 570 times smaller than Madagascar).

The cuckoo-roller is only one of many unique animals that have evolved — or, as is the case for some lineages on Madagascar, were marooned — on these islands off Africa’s east coast.

Out of all the animal species on Madagascar, over 90% are endemic, meaning they’re found nowhere else. Over 100 species of lemurs, half the world's chameleon species, strange shrew-hedgehog-like critters known as tenrecs, odd insects like the long-necked giraffe weevil and giant hissing cockroach, plus plenty of unique birds too: from the couas, a genus of cuckoos with pretty blue-purple faces, to the asities, a small songbird family that also wear colourful masks, the mesites, an order of nearly flightless birds that dash around catching insects, and ground rollers, a family related to regular rollers but distinguished by their terrestrial habits, including nesting in burrows.

The Comoro Islands, while nowhere near as rich as Madagascar (nor as old or large), still host their fair share of endemics: species of fruit bats, pigeons, scops owls, sunbirds, snake-eyed skinks, and day geckos.

(See below: Madagascar endemics in the first two rows, Comoros endemics in the third row.)

In all honesty, the cuckoo-roller is far less intriguing than many of these endemics.

It exhibits no odd hunting strategy: employing a simple perch-and-sally technique, wherein it sits still and surveys its surroundings for prey before darting in for the kill — a strategy employed by plenty of other birds (drongoes, flycatchers, bee-eaters) including rollers.

Its reproduction is fairly standard: most likely monogamous and territorial, nesting in tree hollows, laying 3-4 eggs, incubated by mom and provisioned by dad — a behavioural package shared by vangas, kingfishers, and, yes, rollers.

Its calls, while varied, are not especially artful: a whistled “weeell weeell weeell weeell”, a woodpecker-like “woo we-we-we-war-war”, a high-pitched “pee-eww pew pew,” a parrot-like “nyoo” in flight, or a mournful “krrriioooow” as an alarm.

In a way, those early naturists got it right: the cuckoo-roller is a mish-mash of other bird species. It is ecologically ordinary; more interesting for its evolutionary circumstance than for any particular trait of its own. It is phylogenetically unique. We’ve established that the cuckoo-roller is alone in its entire order, and that is a rare thing. But what exactly does it mean for a species to be unique, in the evolutionary sense? How does a species come to be so alone? And why is the cuckoo-roller so outwardly unremarkable?

The Last of a Lineage

To use a somewhat tired, but still evocative metaphor, let us imagine an animal kingdom Tree of Life: large boughs representing classes and phyla, the branches orders, families, and genera, and the twigs individual species.

At some point, each bough and branch and twig split off from another, and the length of the limbs represent how long ago that split happened. The two great boughs that represent birds and mammals (themselves growing from the reptile bough), split apart some 315 million years ago, and they have each grown long and large, laden with countless branches and twigs. From the branch of songbirds (order Passeriformes), a new diverging twig began to grow some 6 million years ago. It hasn’t grown too long, given the allotted time, but it has become a branch exceptionally rich with twigs: these are the Hawaiian honeycreepers, descending from a single ancestor species and radiating into a colourful group of more than fifty (sadly, only some 17 species now remain).

The point is, a branch doesn’t need to be long to be rich with species. And neither is a long branch guaranteed to have many branches or twigs. That is what the order Leptosomiformes, that of the cuckoo-roller, is: a long, barren branch with a single living species at its end. That is how the lineage of a relict species appears on the tree of life.

If the cuckoo-roller branch has had so long to grow, separate from the rest of the birds, how come its single surviving member didn’t accrue more differences?

A stark counter-example is the only other bird species that is completely alone in its order.⁶

The hoatzin is striking: raptorial, with a large body feathered in shades of orange, brown, and black, a small head with a scanty crest, a bare blue face, and deep red eyes. It clambers through trees in the swamps and mangroves of the Amazon and Orinoco deltas, the chicks equipped with two claws on each wing that allow them to cling and climb before they can fly — and if they feel threatened, they simply drop into the water below and swim to safety. The hoatzin is also known as the “cow bird,” for its diet consists almost entirely of leaves (a food source most other birds don’t touch) and its foregut is full of special bacteria for fermenting this unique diet, not unlike a cow ruminates grass (on a related note, the hoatzin is also known as the “stink bird”).

This relic evolved to become a clawed, swimming, leaf-eating, ruminating species — unlike any other bird alive today. Why? Because this combination of unique traits is what helped its ancestors survive. And it’s the same for the cuckoo-roller, except it converged on fairly common traits shared by many other birds. Showy aerial displays work for rollers, zygodactyl feet work for cuckoos, cavity nesting works for kingfishers, perch-and-sally hunting works for drongoes, and carnivory works for all of the above. The cuckoo-roller evolved these familiar traits because they all worked. So while the cuckoo-roller diverged phylogenetically — its branch split off and grew longer and longer, separate from all other birds — it converged to share familiar physiology and behaviour.

But branches don’t typically grow long and barren. A branch has a tendency to sprout twigs as it grows: that’s called speciation, and it typically happens when populations of the same species are isolated from one another (like the ancestors of Hawaiian honeycreepers were on different islands and in different habitats).

The cuckoo-roller branch split off from all other living birds over 50 million years ago, and we find fossils of early ancestors (or close relatives of those ancestors) from around this time in the Northern Hemisphere. The cuckoo-roller order spawned — speciated into — at least one other discovered genus; Plesiocathartes, known from five fossil species, which are thought to have closely resembled the modern cuckoo-roller with the exception of longer legs and smaller wishbones. These were unearthed in Europe and North America, dating to the Eocene and Oligocene epochs, from about 37 to 28 million years ago. Surely there were more related species whose fossils haven’t yet been found or simply weren’t preserved. Regardless, around the Oligocene, all traces of Leptosomiformes disappear from the Northern Hemisphere.

Somehow they made it down to Madagascar. How?

At this point, Madagascar was already floating free off Africa’s east coast. Did the cuckoo-roller’s ancestors take the route of early Malagasy mammals, arriving from continental Africa, or that of many of Madagascar’s birds, who flew over from South Asia? We don’t know, because we’ve found no related fossils on either land mass. We haven’t even found any fossils on Madagascar. So exactly how long the cuckoo-roller has been there, when it made its excursions to the newly formed Comoros Islands, or how many new species it may have radiated into while colonising these isles, we don’t know.

So much for ancient relatives, but how about modern ones? What branches grow nearest to that of Leptosomiformes — i.e. who are the cuckoo-rollers closest living relatives?

There are two main methods to determine the relatedness of different taxa. One is morphological: which traits does a taxon share with others and how unique are those traits? For the cuckoo-roller, a chimera bird, this method misleads more than illuminates. The second method is molecular: how similar are the genomes of different taxa?

The cuckoo-roller’s placement has historically been very unstable, and even molecular analyses over the last few decades have bounced it around different parts of the avian tree. Early studies grouped it with rollers, kingfishers, and bee-eaters in the order Coraciiformes, then it was placed in its own order and moved near the woodpeckers, and finally…well, there is no finally. One study (Mayr 2008) sequenced different cuckoo-roller proteins and produced two different phylogenetic trees: one placing its family near true owls (Strigidae) and nightjars (Caprimulgidae) and the other near mousebirds (Coliidae) and seriemas (Cariamidae) — in any case, far from woodpeckers and rollers.

Others (Jarvis et al. 2014) think that the cuckoo-roller branch is on the border of a group (clade) known as the Eucavitaves — which includes rollers and relatives, woodpeckers and toucans, hornbills and hoopoes, and trogons. Who in this broad group is the cuckoo-roller most closely related to? We don’t have an answer, and we may not get one. The rapid diversification of these lineages during the early Paleogene (~60 million years ago) has made it challenging to pinpoint a single closest living relative. If the cuckoo-roller lineage truly sits near the base of the Eucavitaves, perhaps as one of the first to diverge, its shared ancestry with all the other groups would lie so deep, so near the many divergences, that the phylogenetic signals become so faint and contradictory as to be practically unreadable.

It would be easier to find its position on the tree if the cuckoo-roller had any surviving relatives, but it does not. None exist on Madagascar or the Comoros Islands, and (as far as we know) there are no long-lost relatives anywhere else. The cuckoo-roller is a relic after all; its relatives are all extinct, all the twigs on its branch have withered except for one.

But just as a taxon — an order, family, genus — can lose its species until just a few, or even a single relic is all that’s left, so can a relic repopulate its lineage. After all, if a single species of songbird can arrive on the Hawaiian Isles and explode into a lineage of over 50 different species, then a raptorial relic from the Amazon, or an odd and lonely bird from Madagascar, also harbour the potential for founding a rich lineage; a limb heavy with new branches and twigs. Perhaps the first new twig has already begun to bud.

Thanks to the cuckoo-roller’s island distribution, its chances of spawning new species is especially good. Indeed, three subspecies of the cuckoo-roller have been identified, and one of them — L. d. gracilis, found on Grand Comore — is different enough in plumage, voice, and size that some already consider it a wholly different species: L. gracilis, the Comoro cuckoo-roller.⁷

What of the cuckoo-roller's future outlook? The species, taken as a whole, is considered to be of ‘least concern’ — especially numerous in plantations and gardens, and common on the islands of Mohéli and Mayotte. But the Comoro cuckoo-roller, like the tiger of Sumatra, is a geographical relic. Although few surveys or studies have been conducted in regards to the subspecies (or potential species-proper), it’s estimated that only around 100 pairs live on Grand Comore. Designated as its own species, low in number and threatened by the destruction of its natural habitat, it would surely be of some conservation concern. Would we nip the bud before it has a chance to grow?

————

The cuckoo-roller may not impress anyone with its appearance or any particular behaviour. Paradoxically, the cuckoo-roller’s oddest feature is just how normal it seems, given how distantly related it is to all other living birds. It is the embodiment of an evolutionary oddity, while itself appearing exceptionally ordinary.

However, like any relic, its significance lies not in its beauty, but what it can teach us and what it represents.

Non-Avian Relics

-

Aardvark

Monito del Monte

Platypus

Mountain Beaver

-

Tuatara

Earless Monitor

Pig-nosed Turtle

Leatherback Sea Turtle

-

Whale Shark

Salamanderfish

Freshwater Butterflyfish

Goblin Shark

¹ While cuckoos are indeed known for brood parasitism, “only about 40 percent of cuckoo species worldwide are brood parasites, the rest care for their own eggs and young” (Stanford University).

² One researcher (Burton, 1983) noted that the “cuckoo-roller's regular consumption of chameleons is certainly unusual, but these would hardly seem to require different adaptations from Coracias [a genus of rollers] which also feeds on lizards”

³ A whole 38 genera (out of ~105) in the tyrant flycatcher family contain just a single species. Some other examples include the ornate flycatcher (alone in the genus Myiotriccus), many-coloured rush tyrant (Tachuris), pale-eyed pygmy tyrant (Atalotriccus), kinglet calyptura (Calyptura), cinnamon flycatcher (Pyrrhomyias), and the drab water tyrant (Ochthornis).

⁴ A monotypic taxon is any taxon that has only a single subordinate taxon within it. So a genus with one species is a montypic taxon, as is a family with only one genus, an order with only one family, and so on up the taxonomic ladder. The cuckoo-roller is monotypic from genus to order — but it’s not a monotypic species, since it does have three recognized subspecies.

⁵ Not to be confused with the Leptosomatidae, which is a family of parasitic nematode worms.

⁶ The cuckoo-roller and hoatzin are the only bird species completely alone in their orders. Two others come close. The kagu and sunbittern — one from New Caledonia, the other from Central and South America; one blueish-grey with a pompous head crest, the other barred and brown with butterfly-pattern wings; one endangered, the other of least concern — each alone in their respective families, are nonetheless (despite their differences), placed together in the order Eurypygiformes.

⁷ It’s important to remember that the details of taxonomy are always liable to change. To return to the well-known metaphor, the tree of life did grow in a particular way — certain lineages gave birth to others, diverging and diversifying: birds and mammals did evolve from the reptile lineage, the honeycreepers from the songbird lineage. But we’re the ones making marks in the bark, placing labels on the tree, deciding where to draw the line between branch and twig, and our judgement is subjective and often imperfect. That’s plain to see by the disagreements and changes that have taken place over the past few hundred years that modern taxonomy — and the ~160 years that phylogenetic classification — have existed.

Where Does It Live?

⛰️ Forests, grasslands, plantations, and farmlands.

📍 Madagascar and Comoros.

‘Least Concern’ as of 28 May, 2025.

-

Size // Small

Length // 45 cm (18 in)

Weight // N/A

-

Activity: Diurnal☀️

Lifestyle: Generally Solitary 👤

Lifespan: N/A

Diet: Omnivore

Favorite Food: Insects and lizards 🦎

-

Class: Aves

Order: Leptosomiformes

Family: Leptosomidae

Genus: Leptosomus

Species: L. discolor

-

The most unique thing about the cuckoo-roller is its uniqueness in itself: it is the sole living species of an entire order. For comparison, other bird orders can have hundreds of species — like the waterfowl (Anseriformes) with some 170 species or the shorebirds (Charadriiformes) with over 380 — or even thousands, with the songbird order (Passeriformes) containing over 6,500 species. The taxonomic category above order is class; in this case the class Aves, encompassing all birds.

The cuckoo-roller combines traits of both cuckoos and rollers: a cuckoo-like silhouette, a rolling roller-like flight pattern, the zygodactyl feet of a cuckoo, the cavity-nest of a roller, and, like both cuckoos and rollers, the cuckoo-roller is primarily carnivorous, taking insects, geckos, and small chameleons. And yet, the cuckoo-roller isn’t closely related to either of its namesakes.

Who is it related to then?

Various relations have been proposed — to woodpeckers and toucans, owls and nightjars, seriemas and mousebirds — yet definitive relatives for the cuckoo-roller are hard to come by. Many bird lineages seem to have diverged quite rapidly during the early Paleogene (~60 million years ago). If the cuckoo-roller lineage branched off around this time, it would share deep common ancestry with many groups and leave only faint signals of where it belongs; perhaps explaining why it's so hard to place on an avian family tree. It would be helpful if the cuckoo-roller had a few living relatives, but it does not.

Could the cuckoo-roller order repopulate its ranks once more?

This species is found only on Madagascar and the nearby Comoro Islands.

Thanks to this insular distribution, the cuckoo-roller’s chances of spawning new species are fairly good; indeed, three subspecies of the cuckoo-roller have already been identified, and one of them — L. d. gracilis, found on Grand Comore — is different enough in plumage, voice, and size that some already consider it a wholly different species. Unfortunately, full species status would almost certainly come paired with an Endangered listing, as only around 100 pairs survive on Grand Comore. Still, the potential is there; we only have to give this loneliest of birds a chance.

-

Birds of the World — Leptosomidae

Relict species: a relict concept by Philippe Grandcolas, et al.

Relict Species: Phylogeography and Conservation Biology by Jan Christian Habel and Thorsten Assmann

Fauna & Flora — Sumatran Tiger

National Geographic — Sumatran Tiger

Genetic Ancestry of the Extinct Javan and Bali Tigers by Haoran Xue, et al.

National Park Service — Relict Leopard Frog

Birds of the World — Bird Species by Taxa

Birds of the World — Hoatzin

Animal Diversity Web — Hoatzin

Evolution Berkeley — Madagascar Geology

Mantle Plumes — Comoros Geology

-

Cover Photo (© Jean-Sébastien Guénette / Macaulay Library)

Text Photo #01 (© Bradley Hacker / Macaulay Library)

Text Photo #02 (© Reece Dodd | Rockjumper Birding Tours / Macaulay Library)

Text Photo #03 (© Luke Seitz / Macaulay Library)

Text Photo #04 (© Marco Valentini / Macaulay Library)

Text Photo #05 (© Dubi Shapiro / Macaulay Library)

Text Photo #06 (© Encyclopedia Britannica)

Text Photo #07 (© Frank Vassen / Wikimedia Commons)

Text Photo #08 (© Encyclopedia Britannica)

Text Photo #09 (© Radosław Botev / Wikimedia Commons)

Gallery #01 (© Simon Willison, © Frank Vassen, © Frank Vassen, © Greg Boreham, © lappuggla / iNaturalist, © Holger Teichmann, © Lev Frid | Rockjumper Birding, © Chris Venetz | Ornis Birding Expeditions, © Chris Venetz | Ornis Birding Expeditions, © Tomáš Grim / Macaulay Library, © Manuel Ruedi / iNaturalist, © Kasper R. Berg, © Ross Gallardy / Macaulay Library, © Emilie Ducouret, © Frank-Roland Fließ / iNaturalist

Text Photo #10 (© Rhys Marsh / Macaulay Library)

Text Photo #11 (© Jon Fjeldså / Josefin Stiller)

Text Photo #11 (© Nigel Voaden / Macaulay Library)

Gallery #02 (Kelly Abram, © Breck Haining, © chris_barnesoz, © rahmadi_aulan, © Franca Wermuth, and Vassil / iNaturalist)

Slide Photo #01 (© Francesco Barberini / Macaulay Library)

Slide Photo #02 (© graichen & recer / Macaulay Library)