Desmans

Desmana moschata / Galemys pyrenaicus

The desmans are the odd duo out in the mole family. Both are semi-aquatic: the Russian desman lives in slow-moving waters, while the Pyrenean prefers fast-moving mountain streams. Desmans were more numerous once, but today these are the last two species left.

Moles

Most people will be familiar with moles: small cylindrical bodies covered in velvety fur, tiny eyes, and no external ears, weak hind limbs, but clawed paws up front for excavating. Worldwide, there exist some forty mole species in the family Talpidae (from the Latin talpa, simply meaning ‘mole’). Perhaps surprisingly, all of them can swim, but some are better at it than others.

The star-nosed mole, famous for its tactile stellate organ, is a proficient diver, submerging itself for 30 seconds at a time to track down aquatic insects by scent — continuously blowing air bubbles and then inhaling them. But most members of the Talpidae family are not ideally adapted to water: while their front limbs make good paddles, their hind limbs are small and weak, and their tails are short. They usually prefer to stay grounded and dry.

The same cannot be said of the desmans.

Desman Duo

Two species stand as the odd pair out in the mole family. These are the desmans. They bump up the Talpidae total to over 40 species — so while it is referred to as the "mole family," it’s actually comprised of 40-some moles plus 2 desmans.

Desmans are unusual, unique, and unknown to most.

Once upon a time, there used to be many species of desman. Scroll the Wikipedia page on desmans and you’ll see an "in memoriam" section listing 5 known species and 7 genera that likely went extinct during the Pliocene Epoch, between 5.3 million and 2.6 million years ago. Certainly, by the end of the 19th century, only two survived: the Russian desman (Desmana moschata) and the Pyrenean desman (Galemys pyrenaicus). And while they are one another's closest living relative, they don't even share a genus — both had many closer sibling species that died out — and, despite the saying that "family sticks together," the two don't overlap in range.

The Russian desman lives in the drainage basins of the great rivers of Eastern Europe — the Don, Ural, and Volga — and ranges through Ukraine, Russia, and Kazakhstan. In the past, it would have needed a different name, for fossils indicate that the Russian desman ranged across Europe, as far as the British Isles. The Pyrenean desman, true to its name, lives in the Pyrenees mountains that straddle the border between Spain and France (and encompass Andorra), and along the northern portion of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal). The two surviving species, all their closest siblings having long since perished, live as two estranged and distant cousins.

Water Bodies

Separated by geography, the two desmans are united in appearance and behaviour.

They are semi-aquatic critters, superbly adapted for wetland life. They wear dark wetsuits of long and dense, water-repellent fur. Their long, scaly, and flattened tails — horizontally flattened in the Russian, vertically in the Pyrenean — act as rudders. In contrast to their fossorial mole relatives, the desmans have smaller front limbs, partially webbed and tipped with sharp claws for grabbing slippery prey, and large hind limbs, fully webbed and fringed with hairs for thrusting through the water. However, despite all the differences, you can still see the family resemblance between moles and desmans in their faces: tiny, almost unnoticeable eyes and a lack of external ears.

Indeed, you could almost mistake a desman’s face for that of a mole, if it wasn't for the snout. Protruding far from its face, flattened and tipped with prominently lobed nostrils, the desman uses its flexible snout to poke and probe for prey along the bottom of streams and ponds. And, like the unique nose of the star-nosed mole, the desman's snout is extremely sensitive, covered in extensive tactile equipment such as vibrissae (whiskers) and Eimer’s organs (complex mechanosensory structures, also found in the snouts of traditional moles). When it discovers a tasty treat — whether it be an insect, crustacean, or fish — the desman’s flexible snout immobilizes it and shoves the morsel into its mouth.

The tail of the desman is a hefty appendage. In the Pyrenean desman, the tail is longer than its actual head-body length. In the Russian desman, it is nearly so. To be fair, the Russian desman is also quite big, as far as Talpidae go — one of the biggest, in fact, measuring up to 22 centimetres (8.7 in), not including its tail.

Some have speculated that the Pyrenean desman also senses its surroundings using sound, specifically the sound it itself makes. By slapping its tail on the water, it's thought to create sound waves which it uses to echolocate. The Russian has been proposed to do the same thing by slapping the water, not with its tail, but with its paws, like a toddler in a pool — odd, as you’d expect the species with the horizontal tail (the Russian) to do the slapping.

Beavers are known to slap their tails on the water, creating loud noises when danger is about to warn other members of their colony. Such a signal wouldn't be of much use to the Pyrenean desman, given that it’s a solitary creature and thus has no one to warn — in fact, it’s known to get into frequent brawls with the other desmans it does meet. The Russian desman, on the other hand, is quite gregarious, but there’s no mention of tail slapping behaviour in the species.

The idea of water-slapping, echolocating desmans, while interesting and cute, is very much speculative and unproven.

Semi-Aquatic

What is well-documented is the desman’s semi-aquatic lifestyle.

Both desman species hunt in water, but their particular preferences differ. The Russian desman favours the relative calm of unpolluted lakes and ponds, or slow-moving streams and rivers. The Pyrenean desman, meanwhile, enjoys cold, clear, and swift mountain streams, typically above elevations of 400 metres (1,300 ft) and up to 2,700 metres (8,850 ft).

After its nocturnal hunt, a desman emerges onto the bank of its river or lake.

The Russian desman employs a crafty bit of engineering: an underwater entrance, leading to its tunnel and up into its subterranean nest chamber. It tries its best to construct a burrow above the highest reach of nearby water, but its mental blueprint often doesn't take into account rapid snow melt and unexpected floods. In Russian desman habitat, during such unforeseen events, you're likely to see a bunch of unhappy desmans ambling about above ground, expelled from their flooded subterranean homes.

But the desman is an adaptable creature. Around the time of spring floods, the Russian species is also known to construct temporary burrows with up to four exits — ready escape routes in case of flooding. If worse comes to worst, and the ground is churning with flood waters, it can create emergency shelters in tree trunks or even in floating hollow logs. And while the Russian desman doesn't seem to adopt the tail-slapping behaviour from beavers, it will use their burrows, hiding in those of Eurasian beavers and muskrats when it doesn't build its own.

The Pyrenean seems to be less particular about its lodgings: it'll clamber out of the water, moving somewhat awkwardly over land, to find itself a nice crevice between some rocks or tree roots for shelter. Or maybe borrow a burrow from a water vole, rarely bothering to dig its own.

Desman territories are marked by scent glands at the base of their tails. The smell is said to be quite strong, and the Russian desman apparently boasts the stinkier scent. The prevalence of these scent-markings is decreasing, however, and despite how that may sound — fewer stinky spots — it is, in reality, a sad reflection of the poor state desmans currently find themselves in.

Desmans in Decline

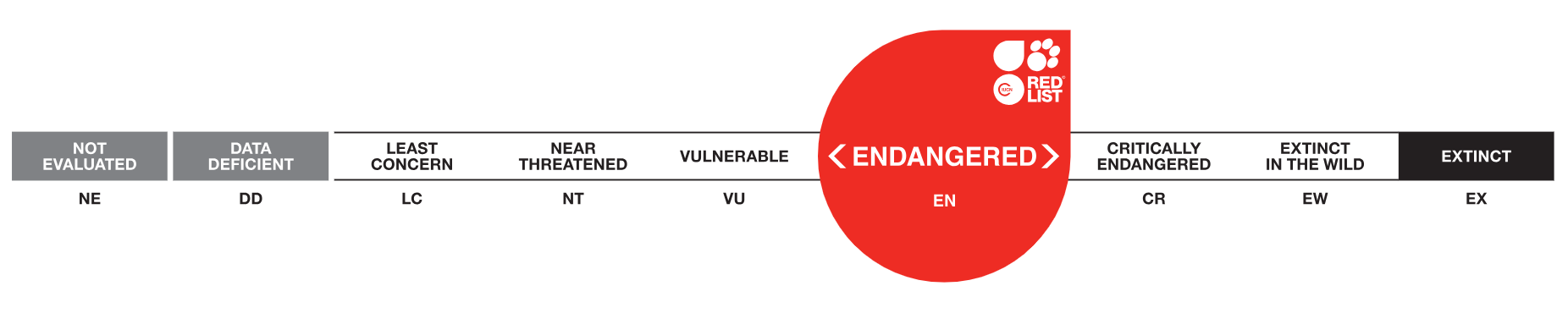

The Pyrenean desman is considered endangered, and the Russian critically so.

Both are creatures of wetlands, a habitat particularly vulnerable to human interference. Pollution, water extraction, habitat fragmentation through river obstruction, clearance of native vegetation, conversion for agriculture...there are countless ways that we disrupt and destroy their watery homes. But the desmans are not just incidental victims of the "human enterprise". There's a whole history of malicious persecution and exploitation.

For the Russian desman, the late 1800s was a time of terror; a period when hunting by humans drastically cut down the population. The Pyrenean, meanwhile, is still targeted and killed by fishermen who incorrectly assume that this little carnivore is a threat to their fish stock. And while the desman is an adept hunter, it is also pretty small, and its prey is diverse — it has little to no impact on a fisherman’s bottom line.

Fishermen are an enemy to both desman species, in most cases, unintentionally (but irresponsibly) so. Fixed fishing nets are left in the water for weeks, months, or indefinitely, abandoned by the fishermen. A Russian desman tangled in a net has, on average, 5 to 10 minutes before it dies. In Portugal, extreme and indiscriminate fishing practices like poisoning and the use of explosives kill the Pyrenean desman as well as fish. And if not harming desmans directly, overzealous fishermen can fish an aquatic ecosystem so excessively that little is left for the desmans to eat.

On top of their rivalry with fishermen, both desmans must also compete with, and avoid, a host of semi-aquatic invaders from the Americas. The nutria (aka, the coypu), from South America, is a competitor for nesting sites. The large and aggressive American muskrat is known to forcefully evict Russian desmans from their carefully constructed homes. And, introduced by fur farms, the American mink is a semi-aquatic mustelid that will hunt most anything, including desmans — while native predators are usually disgusted by a desman’s smell, the mink apparently won’t shun a stinky snack.

Both species of desman have declined by some 50% in ten years. Population surveys of Russian desmans dropped from 27,120 in 2001 to 13,320 in 2009-2013, a 51% reduction. By 2017, counts fell again to 8000–10,000 individuals. The Pyrenean isn’t faring much better.

When the threats are multiple — habitat fragmentation and destruction, hunting, invasive species, etcetera — as is the case with most threatened species, the prohibition of just one practice, or establishment of one law, is often enough to slow a species' plunge towards extinction, but not stop it. Hunting may cease, and so the decline is slowed, but habitat destruction continues, and so the species continues towards its doom.

We cannot be content with hearing, for example, "A law has been passed prohibiting hunting, so the problem has been addressed,” when continued habitat destruction will eventually bring the species to extinction anyways. In almost all cases, there is no single solution, and the problem must be tackled from all angles — economic, political, cultural, educational, etc. Every law passed and conservation action taken is a step towards saving a threatened species. And each step should be celebrated because it means hope, but we mustn’t get stuck on any one step. We must climb the entire staircase, reaching the point where a species' population is stable and self-sustaining.

Saving a Species

A good first step is to gather information on the threatened species: what habitat does it use most, what is its food source, what’s the species' viable population size, and genetic variability?

With this knowledge, it should be possible to identify the major threats to the species.

Is a particularly crucial plot of wetland being drained, or disturbed in some other way, say, by a hydroelectric dam? Is a prey item the species depends on being overhunted? Do certain invasive species compete for the species' niche or directly predate it? Having identified the threats, an effective plan of action can be formulated.

For both desman species, the creation of protected areas — or the establishment of desman populations in protected areas — is one conservation path being taken. The Russian desman holds out in Okskiy, Voronezhskiy, Kaluzhskie Zaseki Zapovednik, and Ugra National Parks, as well as some smaller protected areas. Populations of the Pyreneans reside in a smattering of protected national parks throughout the Pyrenees Mountains.

With knowledge of both species' favoured habitats, plans of action have been proposed for habitat restoration and the management of watercourses, focusing specifically on protecting and restoring the most ideal spaces for the demesan. Further studies on the effects that particular invasive predators have on the desmans are being pursued. For the Russian desman, laws against hunting were declared final in 1957, and stationary fish nets are now prohibited in many regions. Its fight to exist is a little less punishing.

In many cases, however, including that of the Russian desman, laws may be ineffective. The problem might have to be tackled from a different angle: education.

Most people are not aware of the plight of the desmans — most people aren't aware they exist at all — even those that carry out practices which endanger the species. By spreading knowledge of a threatened species, we inform those who are ignorant of their harmful actions, while also placing pressure on governments to uphold laws pertaining to the species, simply by paying attention and letting our worries and wants be known.

An idea to promote the desman as a 'flagship species' has been put forth as a way to both inform people of the endangered animal itself and promote the conservation of their wetland habitats as a whole. Think of the effectiveness of established flagship species, known and beloved by billions around the world: elephants in their savannah ecosystems, tigers in their tropical forest ecosystems, and whales in the vast ocean ecosystems, just to name a few of the most famous. The phrase "think of the turtles!" may be clichéd, but even the least environmentally conscious, about to toss a piece of plastic litter on the ground, may have turtles flash through their thoughts; the image of one starving with a belly full of plastic. Even those who would never call themselves environmentalists often pause at the thought of harming an animal they know and care about. To hear “think of the desmans!” might at first sound strange, but with the right storytelling and visibility, it could carry weight. Every flagship species begins obscure, after all, until one day it becomes the face of an entire ecosystem.

Yes, most people are enticed by the sheer "charisma" of these flagship species, caring first and foremost about saving them, specifically, from extinction. But that inevitably means conserving the habitats and ecosystems that they are a part of — saving millions of other, lesser-known species in the process.

It is a point of hope that millions around the world dedicate their lives to pursuing the protection of threatened species, in every possible way they can. The rest of us can do whatever we can to help, whether that means donating to conservation efforts or just telling a friend about a cool species, and spreading the word so more people care.

Both desman species have their own set of traits that make them unique and, in a way, antitheses of one another — comprising a strange kind of Yin and Yang. The Russian likes the tranquillity of calm waters, the Pyrenean likes the thrilling rush of fast streams. The Russian is a fastidious homemaker, while the Pyrenean crashes where it can. The Russian is a social butterfly, the Pyrenean a lone ranger. By chance and happenstance, by tragedy, no doubt, these are the only two species that remain. After so much irreparable damage, we’re finally learning how to effectively conserve our remaining species, just in time to save our last pair of desmans.

Russian Desman

Where Does It Live?

⛰️ Slow-moving streams, lakes, and ponds.

📍 Southwestern Russia, parts of Ukraine and Kazakhstan.

‘Critically Endangered’ as of 29 Mar, 2023.

-

Size // Small

Length // 20 cm (8 in) body + 20 cm (8 in) tail

Weight // 100 - 220 grams (3.5 - 7.7 oz)

-

Activity: Primarily Nocturnal 🌙

Lifestyle: Solitary and Social 👤 / 👥

Lifespan: Up to 4 years (reported)

Diet: Carnivore

Favourite Food: Aquatic insects and larvae

-

Class: Mammalia

Order: Eulipotyphla

Family: Talpidae

Genus: Desmana

Species: D. moschata

Pyrenean Desman

Where Does It Live?

⛰️ Fast-moving mountain streams.

📍 The Iberian Peninsula; the Pyrenees, northern Spain and Portugal.

‘Endangered’ as of 09 Feb, 2023.

-

Size // Small

Length // 11 - 14 cm (4 - 6 in) body + 12 - 16 cm (5 - 6 in) tail

Weight // 35 - 80 grams (1.2 - 2.8 oz)

-

Activity: Primarily Nocturnal 🌙

Lifestyle: Solitary 👤

Lifespan: Up to 4 years

Diet: Carnivore

Favourite Food: Aquatic insects and larvae

-

Class: Mammalia

Order: Eulipotyphla

Family: Talpidae

Genus: Galemys

Species: G. pyrenaicus

-

Out of some 40+ species in the “true” mole family (Talpidae), none are as divergent as the desmans. Instead of large front paws for digging, they have broad, webbed hind feet for paddling. Their long tails act as rudders while diving, and their flexible, sensor-laden snouts probe the streambed for aquatic insects and larvae.

Despite their shared name, family, and surface similarities, the desmans belong to different genera (Desmana and Galemys), grow to different sizes (the Russian about twice as big as the Pyrenean), inhabit different ranges (corresponding to their common names), prefer different habitats (slow vs. fast-moving water), and even exhibit different levels of sociality; the Russian is a social butterfly and the Pyrenean a lone wolf.

One is also a lot lazier than the other when it comes to housing. The Pyrenean is liable to plop down in a crevice or between some tree roots, or maybe borrow a burrow from a water vole. The Russian, meanwhile, constructs a burrow above the highest reach of any nearby water, often with an underwater entrance, as well as multiple exits in case of flooding.

Desmans used to be far more numerous and wide-ranging, especially during the Miocene (23 to 5.3 million years ago), when they could be found in North America. You can scroll the Wikipedia page on desmans for an “in memoriam” section listing 5 known species and 7 genera that likely went extinct in prehistoric times.

The Pyrenean and Russian desmans are the last two desman species left, and both are threatened by habitat loss, invasive species, and entanglement in fishing gear. The former is endangered and the latter critically so.

-

Animal Diversity Web — Russian desman

Small Mammals Conservation Organization — Russian desman

Animal Diversity Web — Pyrenean desman

Small Mammals Conservation Organization

Cambridge University Press (archived) — The Pyrenean desman an endangered insectivore by Walter Poduschka and Bernard Richard

Britannica — Overview of desmans

Zoo Barcelona — Conservation programme

National Wildlife Federation — Desman decline

Project MUSE — INSECTIVORE COMMUNICATION by Walter Poduschka (Indiana University Press)

Animal Diversity Web — Talpidae family

Penn State Extension — Mole biology and management

National Geographic — Facts about moles

National Geographic — Star-nosed mole

-

Text Photo #01 (© Klaus Rudloff / Wikimedia Commons)

Text Photo #02 (© Cesar Pollo / iNaturalist)

Text Photo #03 (© Igor Shpilenok / Minden Pictures)

Text Photo #04 (© Roland Seitre / naturepl.com)

Text Photo #05 (© Hana Motyčková / BioLib.cz)

Text Photo #07 (© Klaus Rudloff / BioLib.cz)

Text Photo #08 (© David Perez (DPC) / Wikimedia Commons)

Slide Photo #01 (© KD Rudloff / American Society of Mammalogists)

Slide Photo #02 (© David Pérez (DPC) / Wikimedia Commons)

Slide Photo #03 (© Klaus Rudloff / Small Mammals SG.)