Hooded Pitohui

Pitohui dichrous

The hooded pitohui is one of the few known toxic birds. Like poison dart frogs, it builds up toxins in its body — likely from beetles that it eats — storing them most potently in its feathers which can cause an itching, burning, and numbing sensation when touched.

What comes to mind when you imagine a toxic animal?

There are two forms that toxicity typically takes in animals, and you’ve probably been pedantically corrected upon using the wrong one (or done the pedantic correcting). There is venom and poison. One is injected, the other ingested.¹

The former, venom, is usually used for offensive purposes; think a cobra, or some other snake, with glands full of venom and hollow needle teeth for injecting those toxins into prey before swallowing their inert bodies. The latter, poison, is for defense; poison dart frogs secrete it from their skin, certain organs of a pufferfish are loaded with it, and monarch butterflies accumulate it at the expense of their own vitality.

No animal wants to get eaten, and what better defense is there than making oneself a fatal, and thus highly undesirable meal. Predators become wary of these poisonous animals and the poisonous animals lean into it, becoming more conspicuous and colourful to advertise their obvious toxicity. You’d be hesitant, and rightly so, to pick up a colourful caterpillar or mottled frog in the forest — you know the chemical threat such animals may pose. But what about a bird?

The Toxic Bird

Say you find an orange-black bird on the forest floor. It is injured; one of its wings is broken. Will you help it? Do you pick it up?

If you do, you’ll soon start to feel a tingling and numbness in your hand, your skin will start to itch and then burn. If you bring the bird too close to your face, you might feel like you're swiftly falling sick; you begin to sneeze and the inside of your nose burns on every inhale and exhale.

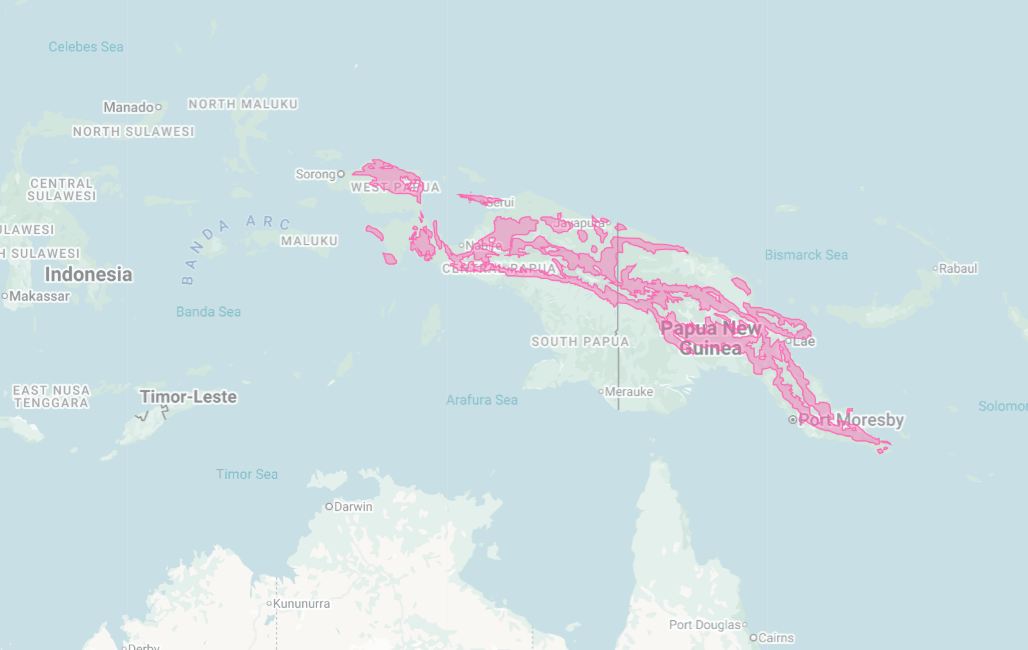

The bird you so altruistically picked up is a mid-sized songbird, found only on the islands of New Guinea.

Locally, it is known as the Pitohui, which translates to, more or less, “rubbish bird” — in reference to the fact that the pitohui is inedible. In 1990, when specimens of this species were being prepared for display in a museum, the scientists handling the skins noticed the symptoms described above. With tingling hands they recorded the first instance of a poisonous bird, one whose toxic effects could be felt through touch alone.

This species, the hooded pitohui, would turn out to be the most toxic bird in the world.

Accumulation

There are two paths to toxicity.

The first is to produce the toxins “in-house” — that is, an animal can make the caustic chemistry within its own body.

Snakes, scorpions, spiders, wasps, lionfish, cone snails, blue-ringed octopuses and almost all other venomous animals possess glands in which concoctions of proteins, enzymes, and other substances are combined to create their toxins. These venomous animals produce different types of toxins, in different glands, and deliver them in different ways — through teeth, stingers, spines, or harpoons — but the concept is the same. Produce and deliver.

But why invest in creating your own toxins when you can steal them?

The second way to become toxic, and the route many poisonous animals take, is to borrow the innate toxicity of others.²

Monarch butterflies devour milkweed plants as caterpillars, storing up poisonous steroids called cardenolides, or cardiac glycosides, that they get from the milkweed. Dogbane leaf beetles do the same with dogbane plants, accumulating and carrying their heart stopping toxins. Burnet moths, meanwhile, accumulate hydrogen cyanide in their bodies by eating plants like bird's-foot trefoil, building up their stores from their time as caterpillars until they’re brimming with poison in their final moth forms. Toxins concentrate as they move up the food chain — from bacteria to plankton to small invertebrates like snails and worms — until they reach the insides of pufferfishes, where they accumulate in the liver and other organs in lethal amounts (not to the pufferfishes, but to anything that tries to eat them).

The poison dart frog is an icon of nature’s deadly chemistry. Brush a millimetre of exposed skin against one of these colourful amphibians and you’ll be dosed with batrachotoxins. These toxins permanently open the sodium channels to your nerve cells, preventing your nerves from firing properly and leading you to suffer convulsions, paralysis, and death from cardiac or pulmonary failure. There is no antidote. However, visit a zoo, and you could hold a poison dart frog in the naked palm of your hand and suffer no consequences.

The difference between benignity and lethality is all in the frog’s diet.

Both captive and wild poison dart frogs eat insects. The former is fed an innocuous buffet of fruit flies, pinhead crickets, and springtails, while the latter hunts down toxic ants, mites, and beetles. None of these insects are ultra toxic individually, but with each noxious meal the poison dart frog sequesters its prey’s toxins in specialized glands beneath its skin until — as is the case with the golden poison dart frog — a single frog accumulates enough poison to kill 10 adult men in just a few minutes.

Once found only in poison dart frogs, batrachotoxins were later discovered in other animals, including a bird: the hooded pitohui.³ The pitohui is thought to borrow the toxins, by way of ingestion, from a group of metallic flower beetles in the genus Choresine, who themselves produce high levels of the stuff. The toxins accumulate, in part, in the bird’s muscle, heart and liver, but the toxins are most potent in its skin and feathers.

Batrachotoxins are among the deadliest group of compounds to be found in nature: fast-acting and ultra potent, with ~2 milligrams sufficiently lethal to kill an adult human. But the worst a hooded pitohui can do — through contact with its skin and feathers — is some numbness and burning. Given that toxicity depends on diet, and diet fluctuates with range, the potency of each individual pitohui also varies (the same goes for poison dart frogs, which also vary between their 175 different species). But, in general, the pitohui’s toxicity is some three times less potent than that of a poison dart frog. Can such weak stuff really be effective in deterring predators? And what other purposes can toxins serve?

Evolving Noxiousness

Toxic Birds

Toxicity is an extremely effective adaptation, and so it has arisen independently in animal groups from insects to octopuses, fish, frogs, snakes, mammals, and birds.⁴ It has done so multiple times independently within most of these groups too.

The hooded pitohui is, as far as we know, the most toxic bird — but it's not the only one.

The majority of poisonous aves hail from the thick tropical forests of New Guinea. Other pitohui species, such as the Waigeo and variable, inherited toxicity from an ancestor along with the hooded. The blue-capped ifrit, a little songbird with a bright-blue halo, is quite unrelated to the pitohuis and must have evolved the ability to sequester batrachotoxin, likewise from Choresine beetles, independently. As did the shrike-thrushes of New Guinea, the regent whistler, and the rufous-naped bellbird. The toxicity of the latter two species was only discovered in 2023 — so surely there are more toxic birds out there than we know.⁵

These birds aren’t any more toxic than the hooded pitohui — that’s to say, their concentrations of batrachotoxins are low — yet they’ve evolved this low-level toxicity multiple times, so it must be of some use.

Warnings & Deceptions

The seemingly obvious answer is that the birds use their poison the same way most animals do: to dissuade predators from preying on them. A poison dart frog is likely to outright kill anything that tries to eat it. The pitohui’s poison, despite its lower potency, might still be enough to kill, or at least greatly sicken a predator like a tree snake or raptor. And perhaps the unpleasant sensation of burning or itching may be enough to convince a predator to find another meal.

Predators swiftly evolve an instinct to avoid anything that can harm or kill them — those that don’t tend to die early, without offspring. This is what gives rise to aposematism: the advertising of toxicity through garish colours or patterns, which poison dart frogs are famous for. A related concept is known as Müllerian mimicry: a kind of collective strategy in which several poisonous species evolve to look alike, to have yellow stripes for example, causing predators to quickly learn to avoid anything with yellow stripes. A group of species engaged in Müllerian mimicry essentially share the cost of educating predators, and then reap the reward of repulsiveness.

There are four species of pitohuis, and they are all toxic to some extent. As with most related species, much of their resemblance can be attributed to their shared ancestry, and so it is through the variation found between subspecies that Müllerian mimicry subtly presents itself.

One species, known as the northern variable pitohui (P. kirhocephalus), is appropriately variable: with 11 recognised subspecies. Most of them have head feathers in shades of light grey and bodies not quite so vividly orange — visibly different from the hooded pitohui — but one subspecies in particular (P. k. dohertyi) very much resembles the hooded. Using genetic analyses to place the subspecies on a phylogenetic tree — mapping their evolutionary relatedness to one another — suggests that P. k. dohertyi is nested deep within the other P. kirhocephalus subspecies. What this likely means is, the many subspecies of the northern variable pitohui lost their resemblance to the hooded pitohui, and then, in one part of the species’ range, one subspecies, P. k. dohertyi, re-evolved that same appearance; likely as a form of Müllerian mimicry with the more toxic hooded pitohui.

Aposematism and Müllerian mimicry effectively work to the benefit of all parties. The predator knows to avoid a certain pattern or colouration (which may be widespread due to Müllerian mimicry), and so avoids the painful or lethal consequences of eating toxic prey. The toxic prey, meanwhile, can avoid being eaten or harassed by predators. But where there is room for exploitation — for employing deception to one's benefit — nature will exploit.

An animal can evolve toxicity and a gaudy appearance, effectively deterring potential predators on sight. Or, an animal can just evolve a similar gaudy appearance to some toxic species, and still reap the benefits of safety without investing in the production or accumulation of toxins. This is known as Batesian mimicry. It is the stingless hoverfly to the stinging bee or wasp, the non-venomous kingsnake to the highly venomous coral snake, it is the edible viceroy butterfly to the poisonous Monarch butterfly. These species look very much like their toxic counterparts, but carry none of their toxicity.

As more and more cheaters exploit a working system, however, that system often ceases to work. The presence of Batesian mimicking species may initially seem benign; they’re not attacking or actively stealing from the species they mimic. Or are they? In a way, they are stealing from their toxic “role-models” — they’re stealing the aposematic signal and, in turn, making it less honest and reliable.

Say there is a frog species that evolved bright blue dots as a signal of its genuine toxicity. Predators will learn to avoid eating any frog with blue dots lest they be poisoned. At some point, another non-toxic species of frog evolves blue dots, and it initially flourishes because it avoids predation without the cost of actually being toxic. But as the non-toxic mimics become more common, some predators will sample them and find that they suffer no consequence. The aposematic signal loses its potency.

The larger the population of the non-toxic mimicking species, the less honest the aposematic signal becomes, and the less likely predators will be to avoid the signal. Everyone suffers: the non-toxic mimicking species is eaten more often, the mimicked toxic species is eaten more often, and predators, now working with an unreliable signal — a free lunch or deadly meal? — will take more chances and get poisoned more often. When cheaters outnumber the honest (toxic) individuals, the system breaks.

There aren’t any species that resemble, one for one, a poisonous pitohui — there are a few “hooded” species with dark head-feathers across New Guinea, like the shining flycatcher, the red-collared myzomela, and eastern hooded pitta, but none are convincing mimics of the hooded pitohui. But if you collect dozens of birds into a flying, foraging flock, each individual becomes harder to distinguish. The Papuan babbler engages in a kind of social mimicry combined with Batesian mimicry. It is of a size with the pitohuis, with plumage a similar shade of rufous-orange. At high elevations, these babblers join up with flocks led by toxic variable pitohuis or hooded pitohuis, even supposedly making the same vocalisations, quite effectively blending in with their poisonous partners. One researcher belatedly noted that “after 200 hours of observation ... I finally realised that not all rufous birds’ [in the flock] were the same species” (Bell, 1982).

The cases of Müllerian and Batesian mimicry in toxic pitohuis is subtle and complicated — not nearly so clear cut as viceroy and monarch butterflies, or king and coral snakes. But if these speculations are true, a good argument can be made that the purpose of the pitohui’s poison is indeed for the preemption of predation.

That’s not to say other hypotheses haven’t been proposed.

Other Uses for Toxins

Some have suggested that the pitohui’s low level toxicity is better explained as a sanitary adaptation: a parasite repellent.

While the pitohui’s batrachotoxins come from insects, specifically beetles, they also appear to be toxic to other kinds of insects. An experiment found that bird lice preferred to inhabit feathers with low or no toxins, rather than poisonous feathers — no surprise. The same seems to hold true for ticks. Comparing the tick-loads of multiple bird groups in the wild, the hooded pitohui turned out to carry among the lowest concentrations of these blood-sucking parasites, and those ticks that did infect toxic pitohui feathers lived shorter lifespans.

The batrachotoxin of poison dart frogs is likewise believed to act as a defense mechanism against microbes, protecting their thin, permeable skin from bacterial and fungal infection. It’s not unlikely that many poisonous animals, especially those whose skin or feathers are covered in their poisons, benefit from some kind of protection from infections. Indeed, compounds discovered in animal toxins have also been beneficial to us. We get blood-thinning drugs like Eptifibatide from rattlesnake venom, antidiabetic drugs like Exenatide from the Gila monster, painkillers like Ziconotide that mimic cone snail toxins, and a particular molecule in funnel web spider venom can be used to prevent damage caused by heart attacks. There’s no reason to suppose these compounds couldn't play similar medicinal or health roles in these toxic animals.

A more unorthodox use of toxins is observed in scorpions, of which several species use their venom-delivering stingers not only to kill, but to court. Scorpions can deliver two types of stings: one with regular venom, that can potentially paralyse, cripple, and kill, and one that only injects ‘pre-venom,’ a clear, less-toxic liquid mainly made of salts. Male scorpions of certain species are known to sting females that they’re attempting to seduce, likely delivering this second sort of pre-venom — potentially as a way to calm the females down, so they don’t use their actual venomous stings on the males.

In pitohuis and ifrits, their varying concentration of toxins, most potent in breast and belly feathers, suggests that they might also be rubbing these toxic feathers onto their eggs and nestlings to protect them from predation and parasites. The pitohui’s toxicity seems to be best explained by both proposed benefits: the toxins both lower parasite load and deter predation. At the very least, we know it works to dissuade the locals of New Guinea from hunting and eating this “trash bird.”

Pathways to Poison

What’s so special about New Guinea that it turns its birds toxic?

Perhaps it has to do with the prevalence of toxic insects: the Choresine beetles that many of these birds eat and get their toxins from. But surely, then, there would be poisonous birds in the Amazon too. After all, poison dart frogs also sequester batrachotoxins (one suggested source of that toxicity are beetles of the family Melyridae). So why didn’t birds evolve to accumulate toxins in South America?

Maybe they lacked the evolutionary pressure to do so. There is a marked difference in predators between South America and New Guinea. On the latter, mammalian predators are scarce, and in their place are plenty of snakes, monitor lizards, and raptors. This shifts the dynamics of the “predator–prey arms race,” possibly making chemical defence a more viable strategy. Why? Maybe because birds and reptiles rely more on vision and movement cues, rather than olfaction, so they’re more likely to bite first and "test" prey directly, creating stronger selection pressure for prey to be genuinely toxic, not simply camouflaged or odorous. Or maybe because such predators tend to be smaller than mammals, making the birds’ low toxicity a more viable defence. The pitohui’s batrachotoxins have indeed been tested on brown tree snakes and green tree pythons, both of which prey on New Guinean birds, and the toxins have been shown to irritate their mouth membranes. Or perhaps it has to do with an increased prevalence of ectoparasites in New Guinea — although that’s just speculation.

A sparsity, or complete lack of mammals is a characteristic feature of many islands around the world. Another island phenomenon is evolutionary boldness. Since islands often feature ecosystems with unusual species compositions, new species arriving on islands are often freed from some previous pressure (predators, parasites, competitors) or are presented with a new opportunity (an open niche, an unexploited food source, etc.), and, as a result, they’re free to evolve in a direction they normally wouldn’t have been able to. This leads to islands fostering unusual traits: gigantism, dwarfism, flightlessness, and perhaps toxicity in animals that normally wouldn’t evolve to be toxic.

Or perhaps it was simply chance. The mutations that confer resistance to batrachotoxins — changes to sodium channel proteins — may be rare and only rarely advantageous. By chance, they may never have arisen in South American birds. But such mutations have arisen multiple times individually in the birds in New Guinea. So what gives?

Why do toxic birds (almost) all take the same route — accumulating batrachotoxins from their diet and storing them in their skin and feathers — to acquire their poisons?

Likely because that path is the one most biologically available to them. What I mean is, if a bird would benefit from being toxic, it would evolve towards that trait by the easiest pathway possible; something in the physiologies of these birds predisposes them to evolving this kind of batrachotoxin toxicity. It could well be a consequence of their genetics. Researchers have found mutations in the sodium channel proteins of these toxic birds which allow them to safely store batrachotoxin in their skin and feathers without poisoning themselves. Perhaps those mutations arise relatively often, or are at least common enough to occur in multiple separate bird groups, allowing them to accumulate poisons through their diets at no risk to themselves. Interestingly, similar mutations have been found in the sodium channel proteins of poison dart frogs. So maybe this route to toxicity — made possible by a mutation that confers resistance — is simply among the “easier” ones to take.⁶ Perhaps, if we go looking, we’ll find more toxic birds.

The repeated evolution of toxicity, through internal production and external accumulation, has given rise to countless intriguing interactions: to partnerships between species, signals between enemies, escalating arms-races, and opportunities for lies and deception. It is an evolved phenomenon that reaches across time, as far back as 700 million years ago — as one of the earliest forms of defence in multicellular animals — across space, present on all six continents and in all five oceans, and across the animal kingdom.

It is not a little astounding that the poison dart frogs of South America and the toxic birds of New Guinea evolved to sequester the same types of toxins (batrachotoxins) from similar sources (insects). Divided by an ocean and some 350 million years of diverging evolution, amphibian and bird nevertheless converge in their toxicity.

¹ There’s another form of toxin which is projected. Known as a toxungen it is defined as “a secretion or other body fluid of one or more biological toxins that is transferred by one animal to the external surface of another animal via a physical delivery mechanism.” That is, through spitting, spraying, or smearing. A spitting cobra (e.g. a ring-necked spitting cobra) delivers venom when it bites, and a toxungen when it spits.

² While the production of toxins is commonly associated with venomous species, a few poisonous ones also do so.

A cane toad's toxin-making glands are large, protruding things behind its eyes that produce and secrete a milky substance made from a mix of steroid-derived molecules known as bufotoxins (“toad” toxins). Many poisonous salamanders and newts also produce their toxins in obvious glands that, in some species like the emperor newt, appear as pretty rows of colourful dots.

Fireflies, with over 2,000 species worldwide, go about toxin production in both ways; many produce their own toxins known as lucibufagins, while species of the Photuris genus — known as “femmes fatale” fireflies — get their toxins by eating those other toxin-producing fireflies.

Blister beetles are so called for the skin-blistering substance, known as cantharidin, which they produce. Interestingly, it’s primarily the males that make cantharidin, and they transfer it over to females as a ‘nuptial gift’ prior to mating. One sex produces, the other borrows.

³ Indeed, the name comes from the Greek word “batrachos” (βάτραχος), which means frog. So the bird accumulates a “frog” toxin. More specifically, the pitohui stores homobatrachotoxin, a derivative of batrachotoxin.

⁴ That’s not even mentioning the countless plants that evolved to be poisonous. Nicotine, for instance, is a potent neurotoxin to many insects and grazing animals — on top of that, it also doubles as a chemical signal, attracting predators of leaf-eating caterpillars. However, in the case of nicotine in tobacco, its defences backfired somewhat when humans began to harvest the plant for chewing and smoking. Some plants evolved their poisons to protect themselves against specialist-type insects, often leading to chemical arms-races over evolutionary time. For example, milkweed produces cardiac glycosides that can poison most insects, but monarch caterpillars evolved to resist and even sequester the toxins. In response, some milkweeds add different glycoside variants to fight back or ramp up the flow of toxins. In turn, caterpillars evolve behaviour to cut off the flow of toxins, and so on…

⁵ There are the toxic birds of New Guinea, and then there is the common quail. This rotund, terrestrial bird has long been the cause of an illness known as coturnism, which causes tenderness and the breakdown of muscles. The only way to suffer this quail-caused illness is to eat one.

Cases of coturnism have been mentioned in 4th century BCE writings from Ancient Greece and Rome, as well as the Old Testament, which recounts that many Israelites, during their exodus from Egypt, died after partaking in this poisonous bird. Coturnism caused by quail seems to have plagued humans, hungry for fowl, since antiquity.

More recent poisonings have occurred in modern Greece, and especially on the island of Lesbos. Why on this seemingly random island in the East Aegean? Because this is where Common quail stop during their migrations between Africa and Europe. Curiously, quail are only toxic during migration, and only on their southward journey from Europe to Africa in autumn.

In the 10th-century text Geoponica — written for the Byzantine emperor Constantine VII — it says that “quails feeding on hellebore are pernicious to the persons that eat them, causing convulsion and giddiness” (citing ancient Greeks like Pliny Aristotle, and Galen as the sources). Hellebore — a brutish name for a group of rather pretty flowers, although quite fitting too, for many are poisonous. This plant has been suggested as one source of the quail's toxicity, while others suggest hemlock or the seeds of annual yellow woundwort; all plants that grow in Europe and could be eaten by the quail before migrating south. Whatever poisonous plants the quail eats, it takes up their toxins just as the pitohou does, itself seemingly unaffected while it accumulates poison in its flesh.

Geoponica continues on the topic of quail, “you are to boil millet along with them : and if a person having eaten them be taken ill, let him drink a decoction of millet.” The toxicity of a quail cannot be ascertained by smell or taste, and neither can its accumulated poisons be boiled or cooked out — whether with millet or without. It’s better to just not risk it.

⁶ Tetrodotoxin are found in pufferfishes, blue-ringed octopuses, rough-skinned newts, and even some frogs. Cardiac glycosides evolved independently in milkweed plants, cane toads, and some beetles (e.g. blister beetles). Formic acid sprays arose independently in ants and some beetles (such as certain carabids) as a chemical deterrent. Certain toxins just work, and so such separate lineages as plants, beetles, and toads, have independently evolved them.

Other toxins are more unique. The slow-loris, the world’s only toxic primate, has a two-step venom that requires the mixing of an oily secretion from the brachial gland under its armpits with enzymes in the loris's saliva (Fitzpatrick, 2023). Meanwhile, the platypus, that duck-billed semi-aquatic monotreme, has a venom (delivered by a spur on the hind limbs of males) made up of 19 peptides along with non-peptide components, some related to those found in reptile venom, some not, with five toxins so-far found only in platypus venom, as well as other “unidentified fractions” (Whittington & Belov, 2007).

Where Does It Live?

⛰️ Rainforests, forest edges, and mangroves.

📍 Islands of New Guinea.

‘Least Concern’ as of 07 August, 2018.

-

Size // Small

Length // 22 - 23 cm (8.7 - 9.1 in)

Weight // 65 - 76 g (2.3 - 2.7 oz)

-

Activity: Diurnal☀️

Lifestyle: Social 👥

Lifespan: N/A

Diet: Omnivore

Favorite Food: Berries and insects

-

Class: Aves

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Oriolidae

Genus: Pitohui

Species: P. dichrous

-

Endemic to the islands of New Guinea, the pitohui’s name comes from a local word which translates to, more or less, “rubbish bird.” This is not a character judgement, but a reference to the pitohui’s inedibility as a result of its unexpected toxicity.

The hooded pitohui doesn’t produce toxins, but is instead thought to get them from a group of metallic flower beetles in the genus Choresine, which it consumes. In this way, it is similar to poison dart frogs — who likewise aren’t inherently toxic.

Indeed, the pitohui is more like those infamously poisonous frogs than you might expect (given the distant relation between the two): both animals accumulate the same type of toxin, batrachotoxins, although in different forms.

Batrachotoxins are among the deadliest group of compounds to be found in nature: fast-acting and ultra potent, with ~2 milligrams sufficiently lethal to kill an adult human. But the worst a hooded pitohui can do — through contact with its skin and feathers — is some numbness, itching, and burning. Given that toxicity depends on diet, and diet fluctuates with range, the potency of each individual pitohui also varies.

The low toxicity of the pitohui may well deter predators from consuming it, but it seemingly also acts as a parasite repellent. Comparing the tick-loads of multiple bird groups in the wild, the hooded pitohui was found to carry among the lowest concentrations of these blood-sucking parasites, and those ticks that did infect toxic pitohui feathers lived shorter lifespans.

Birds likely aren’t the first thing you think when you think of toxic animals, but there are actually a fair handful that we know of, including a few other pitohui species, blue-capped ifrit, the shrike-thrushes, the regent whistler, and the rufous-naped bellbird — all native to New Guinea. (The common quail can also be toxic, likely because of some plant that it eats during migration, but its toxicity only becomes apparent when one tries to eat it.)

At high elevations, Papuan babblers join up with flocks led by toxic variable pitohuis or hooded pitohuis, even supposedly making the same vocalisations, quite effectively blending in with their poisonous partners. One researcher belatedly noted that “after 200 hours of observation ... I finally realised that not all rufous birds’ [in the flock] were the same species” (Bell, 1982).

-

Poisonous pitohuis as pets by Vincent Nijman, et al.

Phylogeny of the avian genus Pitohui and the evolution of toxicity in birds by John P. Dumbacher, et al.

SKIN AS A TOXIN STORAGE ORGAN IN THE ENDEMIC NEW GUINEAN GENUS PITOHUI by JOHN P. DUMBACHER, et al.

Toxic birds: defence against parasites? by Kim N. Mouritsen and Jørn Madsen.

University of Copenhagen – Neurotoxin-Laden Feathers Discovery

National Geographic – Poisonous Birds of New Guinea

Buffalo Bill Center of the West – Poisonous Birds

Encyclopedia.pub– Toxic Birds Overview

Natural History Museum – Sting of Love

Discover Wildlife – Most Venomous Animals

Geoponica – Quails (Archive.org)

ScienceNordic – When Poison Takes Flight

Platypus Venom: a Review by Camilla M Whittington and Katherine Belov.

Max Planck Society – The dark cost of being toxic

ScienceFocus – How do snakes produce venom?

Carnegie Museum of Natural History – Cone Snail Toxins

MSD Veterinary Manual – Cantharidin toxicosis in animals

ScienceDirect – Batrachotoxin (topic overview)

Natural History Museum (UK) – Toxic talents: cyanide moths

Animal Diversity Web – Chrysochus auratus

Zoo Atlanta – The World of Poison Dart Frog Toxicity

Rainforest Alliance – Poison Dart Frog

-

Cover Photo (© Dubi Shapiro / Macaulay Library)

Text Photo #01 (© Nils Schumacher / iNaturalist)

Gallery #01 (© David Tibbetts, © Nick Hobgood, © Anne SORBES, © Roberto Pillon, and © Felipe Rabanal / iNaturalist)

Text Photo #02 (© Dumbacher, et al., 2004).

Gallery #02 (© Chris Venetz | Ornis Birding Expeditions, © Dubi Shapiro, © Zebedee Muller, © Dubi Shapiro, and © Thierry NOGARO / Macaulay Library)

Gallery #03 (© Lioneska, © hobiecat, © Tomaz Nascimento de Melo, © evangrimes, © Ad Konings, and © Lisa Hill / iNaturalist)

Text Photo #03 (© Robert Lockett / Macaulay Library)

Gallery #04 (© Shreybae, © Yinan Li, © uwkwaj, and © Tim Bawden / iNaturalist)

Text Photo #04 (© Dev Anand Paul / Macaulay Library)

Gallery #05 (© Steve Kerr, © Katja Schulz, © 昆虫学liuye, and © Jonathan Numer / iNaturalist)

Text Photo #05 (© Marco Valentini / Macaulay Library)

Slide Photo #01 (© Dubi Shapiro / Macaulay Library)