Island Canary

Serinus canaria

The island canary — native to the Canary Islands, Madeira, and the Azores — is the wild ancestor of the domestic canary. It was bred to be garishly coloured, to have different haircuts and postures, and to imitate the songs of other birds or the sound of babbling water. Later, it was used to detect dangerous gases in coal mines.

A little wire cage swings gently, hooked to a man's belt.

In the cage perches a little songbird with bright yellow feathers, otherwise unremarkable — the archetypal image of a songbird. Its music is melodic and sweet, like a chorus of wind instruments, and one can almost glimpse the notes floating from its open beak. The yellow songbird continues to twitter, as it's carried downward into the dark, at the miner's hip.

Very few birds go willingly into the underworld. There are a few cave-dwellers like the cave swiftlet, which builds nests from its saliva on vertical cave walls, or the oilbird, an altogether odd bird which both roosts and breeds in caves — the only bird known to navigate by echolocation. Most of birdkind, however, prefers the open skies to subterranean claustrophobia.

The island canary is very much a creature of air and light. Its plumage isn't wholly yellow; more like sun dappled through a thicket, with shadows brushing its wings and back. Neither is it very big, only some 13 centimetres (5 inches) long. But, as it darts between low bushes — one moment flashing gold, the next vanishing against the backdrop — the island canary exemplifies the fluttering freedom we so envy in birds.

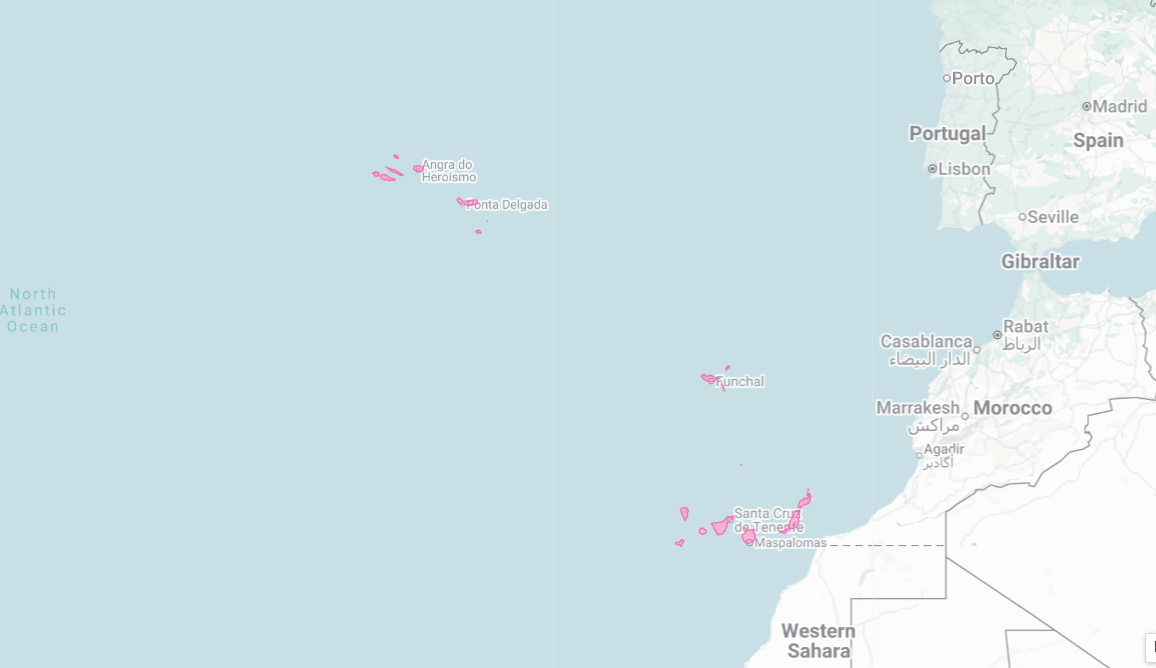

The islands in its name are three Atlantic archipelagos that trace a line from the Iberian coast down along northwestern Africa: the Azores, Madeira, and the Canary Islands.¹ It flits through the humid laurel forests of the Azores. It flies low across the open woodlands and cultivated terraces of Madeira. On the Canaries — where the largest wild population is found — it inhabits moist forest on La Gomera, dry open woodlands on El Hierro and La Palma, and pine woods and coastal scrub on Tenerife and Gran Canaria.

The canary’s song weaves together the soundscapes of these islands; if not the main piece, then at least a bright, lively refrain.² He, for the male canary is the principal vocalist, perches hidden in the treetop or sits exposed on a songpost, like a singer commanding a stage. His song is rich, sweet, and melodious — all the appraising words you could heap upon a piece. It is the whistling flute and a trilling pipe. It rises and falls, from rapid and energetic chorus to quieter, more meditative phrases. From his catalogue of musical syllables, both innate and learned, he composes a piece that would deter his would-be rivals and attract fair suitors. He composes a piece so pleasing and special that it catches the ear of unintended admirers.

Domestica

Down in the mine, the canary's song is muffled. Its notes hit bare rock walls and fall flat onto the dusty ground. Its entire view is reduced to the dim spotlight from the miner's helmet. The air is stagnant, almost suffocating. The caged canary finds itself in a world far removed from its natural state. But this canary, this particular bird, has never known the wilds of the Azores, Madeira, or the Canary Islands.

All three archipelagos were discovered in the early to mid-1400s — during the Age of Discovery in Europe — with the Azores and Madeira going to Portugal, while the Canary Islands became a part of Spain. Impressed by the song of a particular yellow bird native to the islands, Spanish and Portuguese sailors caught a few and brought them back to mainland Europe. For their liveliness, their song, and their exoticism, the canaries quickly became popular with the lavish and sophisticated types — and those who wanted to be seen as such.

In the 17th century, canaries began to be bred in captivity by the Spanish and sold off to Portugal, France, Italy, and England — but only the males, as Spain intended to keep a monopoly on canary breeding. That monopoly didn't hold for long. According to one tale, a Spanish ship was caught in a storm and crashed off the coast of Italy. The canaries aboard the ship escaped to the Italian island of Elba, where they interbred with native serins.³ And so the Italians, from this hybrid stock, would begin breeding them too. Or so the story goes. More likely, however, was that a few Spanish canary breeders made an error while sexing their birds and accidentally sent off a few females with their males. Dramatic shipwreck or mundane error, the Spanish monopoly over canary breeding eventually broke, and the rest of Europe began shaping these much-lauded birds to meet their various whims and desires.

Canaries were bred and trained to sing more elaborate songs. The German Roller was the first song canary to be bred, ventriloquising a quiet tune with a closed beak, less chorus and more accompaniment. Conversely, the Spanish Timbrado Canary is one of the loudest of the canary breeds. Its metallic voice pipes out songs composed of 12 notes, with the name 'Timbrado' coming from the Spanish for "ringing" ('timbre' meaning "bell"). The Belgian Waterslager Canary was the old-timey version of a relaxing ambience track, its song reproducing the babbling of water. Meanwhile, breeders of the Russian Canary took advantage of the bird's mimicking ability, teaching it the songs of other wild birds, and bringing the countryside into cities like Saint Petersburg.

In Germany, the grey-green-yellow plumage of the wild canary was bred into an almost cartoonishly pure yellow. In England, the canaries were made to be orange-red, fed a diet of cayenne pepper while moulting. Blue canaries were bred, and canaries of pure white, lacking any pigment.

Like figures shaped from clay, canaries were made into various shapes, sizes, and styles, sorted under various names: Llarguet Españols, long and slender bodied, Norwich Canaries, heavyset and broad-chested, Border Fancies, rounded and plump, and Belgian Canaries, hunch-backed like miniature vultures. We made lizard Canaries sporting yellow caps and scaly plumage, Parisian Frills with wild whirlwinds of cottonlike feathers, and German Crested and Gloster Fancies with endearing “bowl-cuts.”

Through centuries of deliberate breeding, these canaries became something altogether different from Serinus canaria, the “wild canaries” found on their Atlantic island. They became — or rather, they were moulded into — Serinus canaria domestica.

The domestic canary.

Canary in the Coal Mine

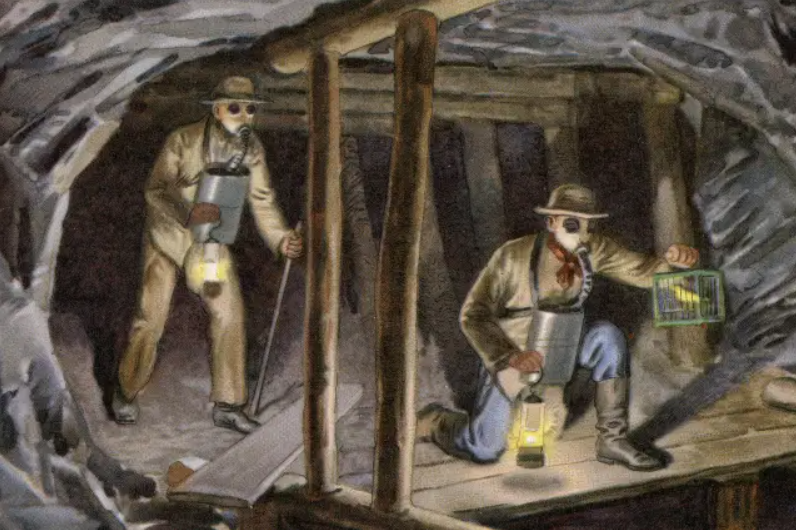

Each hit of the miner's pickaxe and stab of his shovel rattles the canary's cage. Frequently, he pauses in his work for a few seconds, listening for the twitter of song. Stressed in this dark and unnatural environment, the canary isn't much inclined to sing. Periodically, the miner unhooks the cage at his belt and inspects the bird inside. It tilts its head and stares back at him with gleaming black eyes. He returns to his digging.

He puffs with exertion, working for hours in this cramped, stifling space. And he begins to feel lightheaded. Is it exhaustion, or else...? He stops, and he can't hear the canary sing. Not a single peep or tweet. Once again, he unhooks the cage and shines his light inside. The yellow canary, a small slice of sunlight in the dark of the mine, lies motionless.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, coal mining was among the most dangerous of occupations. Miners would risk injury working with heavy equipment in a dark, cramped, and often damp environment. They risked long-term health issues, such as black lung, from poor ventilation and dust inhalation. They risked becoming blocked or buried by a tunnel collapse. And they risked abruptly dropping unconscious and, soon after, dying — poisoned by toxic, odourless gases.

'Whitedamp' is the name given to a mixture of noxious gases that enters a mineshaft undetected, leaking from seams in the rocks. As carbon monoxide, its main constituent, leaks into the enclosed space, it raises no sensory alarms — it is invisible and odourless — but eventually begins to cause weakness, dizziness, and confusion in anyone who breathes it. And it only needs to suffuse a tiny proportion of the air (around 0.1%) to kill a grown man in minutes. It takes a far lower concentration to kill a 15-gram bird.

Following a series of deadly, carbon-monoxide-related mining accidents in the late 19th century, a Scottish physician by the name of John Scott Haldane proposed that some small animals be carried by miners going about their work. Little, warm-blooded animals with high metabolisms would exhibit the symptoms of carbon monoxide poisoning far earlier than a larger animal (like a human). While white mice were used beginning in 1896, ultimately, the rodents would be replaced by canaries around 1900, as the birds showed more obvious signs of distress from poisoning.

With the turn of the 20th century, the bird admired across Europe for its beauty of body and song became a crude tool with a single purpose, for which it would sometimes be sacrificed. The canary's song, from an esteemed performance, would become a reassuring lifeline for workers in coal mines. Giving its breath, and sometimes it's very life and death.

It became an early warning system. A martyr to the march of industry.

The canary's ability to warn of dangerous gases proved so useful that it was employed outside of coal mines. For instance, the little sunny bird was an unwilling participant in World War I.

Canaries were considered a “cheap and sensitive warning device in warfare,” alerting soldiers to dangerous gases in trenches and tunnels. But beyond their practical uses, these birds likely also brought a measure of comfort and levity to the bleakness of the front lines. An English newspaper wrote that "In one company, a certain canary became a regular 'old soldier.' On entering a mine, he would topple off his perch immediately, and pretend to be dead. On being taken out of the mine, he would 'recover' at once and hop about the cage and chirp merrily as though he enjoyed the joke." In another company, a commander kept careful records of his birds, and after one had been gassed three times, he "promoted" it. Its new post? Perched in the headquarters dugout, singing for the commanding officer.

Unfortunately, canaries could also become liabilities. One canary is known to have "deserted" — either escaped or released — from its English company and fluttered into No Man’s Land. The soldiers tried to eliminate the deserter with a sniper rifle, but they missed their small target, and the bird fled towards the German wire. Things became serious, and they decided it was time to escalate. The company put their trench mortars to use, and after the first explosive round, they could spot the feathered renegade no more. Why the bullets and heavy artillery to take down a single bird? Were they scared it would sing their secrets to the enemy? In a way, yes. "The reason was that mining was being carried on at that particular spot, unknown (it was hoped) to the Germans. Had they spotted the canary, the secret would have been revealed."

Canaries were part of the arsenal of war well into the twentieth and even the twenty-first century — participating in the Gulf War under the codename ELVIS (Early Liquid Vapour Indicator System) and in the Iraq War, where they were “the only chemical weapons detector available” to locals in Baghdad. The birds were also used to detect dangerous gases after terrorist attacks: "In 1995, following the Tokyo gas attacks, Japanese troops wearing chemical warfare gear were seen clutching cages of canaries as they stormed the home of Aum Shini Kyo cult's 'Sixth Santium', where the gas was allegedly manufactured."

But while canaries continued to be used in war and counter-terror operations, their stint in the mines was coming to an end. By 1981, "electronic noses" — digital gas detectors — had become common and reliable, and the British government pushed to take the canary out of the coal mine. As for the miners, many lamented the absence of their bird companions: "There is something about hearing them singing when you start work that lifts the spirits. There's no doubt collieries [coal mines and associated buildings] will be less colourful and quieter places without them."

In Britain, the use of canaries in coal mines was officially outlawed in 1986.⁴

Warnings

A canary in the coal mine was an involuntary sentinel, warning the miners when something went wrong, when it was time for them to act — in their case, to evacuate.

Today, the phrase "canary in the coal mine" refers to anything that provides an early warning of danger. The sentinel need not be a canary, and the danger need not be a toxic gas. Across history, many other animals have served as sentinels. There are the quite literal sentinels: guard dogs, for instance, who stand watch over your home and alert you to intruders. But such sentinels don't capture the tragedy of the canary. Unfortunately, sentinels must often make some kind of sacrifice, often unwillingly. Sometimes that sacrifice is their life.

Starting in the 1950s, the cats around Minamata Bay, southern Japan, began to act strangely. They twitched. They staggered. Some convulsed and leapt involuntarily — a condition locals came to call “dancing cat fever.” Crows and other birds living near the coast began falling from the sky. Fish floated to the surface, belly-up. And then the villagers themselves began to show similar symptoms: tremors, slurred speech, hallucinations. The cause was mercury, discharged into the bay by a chemical factory, and concentrated through the food chain. The cats had been the first to show signs of the poisoning. They had been the sentinels.

A cheerier story comes out of Poland, where teams of freshwater mussels — bivalves related to clams and oysters — monitor the drinking water in 50 treatment plants across the country, including the facility that supplies Warsaw, Poland's capital city of 1.8 million. While chemical tests check for known pollutants, they can't always detect every threat in real time. Mussels, on the other hand, are famously picky about water quality. When exposed to contaminants, they simply shut their shells. In the treatment plants, mussels are grouped into teams of eight and fitted with magnetic sensors. If four or more of the mussels shut their shells at once, the water supply is cut off and investigated for dangerous contaminants before it reaches the people of Poland.

In their natural habitats, mussels act as a different kind of sentinel. They're not fitted with sensors or tasked with protecting cities, but they do filter water for a living — sifting out nutrients, silt, and whatever else is suspended in the flow. As they do so, toxins like pesticides, hydrocarbons, and metals accumulate in their tissues. And so mussels are especially vulnerable to pollution, as well as sedimentation and temperature shifts — most any change that can occur in an aquatic system (which is what makes them such good "quality evaluators" in the water treatment facilities). When mussel populations decline or vanish, it's often a sign that something has gone wrong, not just for them, but for the entire ecosystem. Mussels are ecological sentinels; "canaries" of the coasts and riverways.

More formally, these kinds of sentinels are known as indicator species.

Further out at sea, reefs of coral respond dramatically to shifts in water temperature by releasing their symbiotic algae — turning white in the process as they lose their pigment — and to changes in acidity, with an increase making it harder for them to build and maintain their skeletons. As reefs of once colourful coral become bleached and withered, the change is hard to miss. Less obvious is the wearing down of shells in animals like clams, oysters, snails, and sea urchins for the same reasons. Corals, sensitive to change, visually striking, widespread — as well as the base for one of the most biodiverse biomes on Earth — provide the first signs that an aquatic ecosystem is under stress. They are a warning of broader environmental shifts that threaten entire marine communities.

Frogs are like living sponges (the cleaning implement, not the animal). With their permeable skin, they can exchange oxygen with their environment, even when underwater. Whatever else happens to be in the water — whether that be pesticides or heavy metals — may seep in as well. For the frogs, the consequences are (predictably) not good, but this unique sensitivity is what makes these amphibians such excellent bioindicators. Their health reflects the state of both air and water quality, habitat integrity, and broader ecological changes.

Across the world, scientists have observed alarming trends in amphibian populations: mass die-offs, deformities, and unexplained population crashes. Often, these signs appear before the effects of disruption — the consequences of pollution, habitat alteration, or a change in climate — can be noticed in other animal groups. In Costa Rica, for example, the extinction of the golden toad in the 1980s was one of the first warnings of climate-driven disruption in highland cloud forests. In Minnesota, malformed frogs with missing, extra, or malformed limbs were discovered in wetlands, prompting investigations that uncovered a mix of chemical pollution (pesticides and herbicides) and parasitic infection (by trematode flatworm) as the culprits. And in Australia and Central America, chytrid fungus — a disease that thrives in disturbed environments and is often spread by introduced frogs — has devastated dozens of frog species, their deaths a clear warning sign of a disruption to the ecosystem.

These are the most sensitive species; those that might perish from the smallest amount of disturbance. Others may persist longer, just as a human can outlast a canary in a mine leaking carbon monoxide. But eventually, if no action is taken, even the hardiest will perish. The miner will surely die if he ignores the warnings of his caged canary.

The miner stands outside, gasping in fresh lungfuls of air. Once he's caught his breath, he tends to his bird. He opens the door to its cage and picks up the canary from where it lies unmoving on the bottom. He walks over to a strange contraption: a sealed glass-and-metal box with a canister of oxygen on top. The miner places the stiff canary into this resuscitation cage and turns a valve, letting the oxygen flow in. He stares through the window and waits.⁵

Nothing. Nothing. Nothing. Then the canary twitches. It moves its wings a bit. It raises its head and looks around as if awoken from a long nap. It slowly gains its feet and tucks in its wings. Its small chest rises and falls, taking in the clean air. It lets out a quiet whistle.

The miner stares at the bird that saved his life. The canary stares back at the miner for whom it nearly died.

¹ Today, the bird is more famous than the islands it hails from, but it was the islands — the Canary Islands, and, specifically, Gran Canaria — that gave the bird its name. The islands, in turn, got their name from dogs (with the name Canaria coming from "canis," Latin for dog). Are the Canary Islands known for their dogs? No, at least they aren't today. One theory suggests that the Guanches, the islands' Indigenous people, kept or revered large dogs. Another theory proposes the name referred to monk seals ("sea dogs") often seen around the islands. So the bird is named after a set of islands, named after some dogs (or seals).

² The Azores, Madeira, and the Canary Islands — together with Cape Verde, even further south — are collectively known as Macaronesia.

A few other songbirds are endemic to these islands:

The Azores bullfinch lives only in the laurel forests on the eastern end of São Miguel Island in the Azores.

The Madeira firecrest is endemic to the island of Madeira.

The Tenerife blue chaffinch is endemic to Tenerife in the Canary Islands.

The Gran Canaria blue chaffinch is endemic to Gran Canaria in the Canary Islands.

The Canary Islands chiffchaff is endemic to the western Canary Islands, including Tenerife, La Palma, La Gomera, and El Hierro, but is absent from some of the eastern islands.

The Cape Verde sparrow and Cape Verde swamp warbler, endemic to the Cape Verde archipelago.

³ The European serin is another little, grey-green-yellow songbird, which lives across much of Europe and parts of North Africa. It is the closest living relative of the island canary.

⁴ Not too long after, in 1999, the last "pit pony" was retired. What is a pit pony? The word "pony" is a bit misleading here, as horses of all types and sizes — from tiny Shetlands to tall Cleveland Bays — were put to work, hauling coal in the pits.

Beginning in the mid-eighteenth century, they were used to pull heavy tubs of coal along narrow underground rail tracks in coal mines. A mining job for a horse was just as dangerous, if not more so, than for a miner, and while some miners were affectionate towards their pit ponies (as they were toward their canaries), the ponies nonetheless had to endure harsh, cramped, dark environments, just by the nature of the job. Many pit ponies would spend most of their lives in the dark, only allowed up for special occasions like holidays or when a mare gives birth.

At their peak in 1913, over 70,000 pit ponies worked in British coal mines.

By the turn of the Millennium, none did — replaced by mechanised haulage systems: rubber-tyred shuttle cars, conveyor belts, diesel and electric locomotives, and, later, battery-electric vehicles.

⁵ A canary often had a chance to recover from carbon monoxide poisoning.

The resuscitation cage was a metal box with glass windows and a tank on top that would pipe oxygen inside it. Often, a canary would be carried into the mine inside this cage, with the circular door left open and a metal net preventing its escape. If the canary showed signs of carbon monoxide poisoning, the door to the cage would be sealed, and the oxygen released, assisting in its recovery.

Where Does It Live?

⛰️ Varied habitats, from forests to open areas like fields and deserts.

📍 The Canary Islands, Madeira, and the Azores.

‘Least Concerned’ as of 09 Aug, 2018.

-

Size // Small

Length // 13 cm (5 in)

Weight // 15 - 25 g

-

Activity: Diurnal ☀️

Lifestyle: Mostly Solitary 👤

Lifespan: 10 - 15 years

Diet: Omnivore

Favorite Food: Seeds, insects, fruits, berries, and other vegetation

-

Class: Aves

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Fringillidae

Genus: Serinus

Species: S. canaria

-

The wild island canary is a much less gaudy bird than many of its domestic breeds — its feathers dirty yellow and dark green — and its song, though less varied than those of its domestic forms, is still complex and melodious.

Wild canaries were brought to Spain in the 15th century, shortly after their namesake islands were first explored by Europeans (the islands themselves named after dogs, with the name Canaria coming from "canis," Latin for dog). For their liveliness, their song, and their exoticism, the canaries quickly became very popular.

In the 17th century, Spain held a monopoly over canary breeding, selling them to Portugal, France, Italy, and England. One story goes that a Spanish ship crashed off the coast of Italy, and the canaries aboard the ship escaped to the Italian island of Elba where they interbred with native serins. And the Italians, from this hybrid stock, began breeding them too. A more likely scenario, however, was that a few Spanish canary breeders made an error while sexing their birds and accidentally sent off a few females with the males.

Over the centuries, canaries were fashioned into many different breeds. They were bred and taught to mimic the songs of other birds, reproduce the babbling of water, and ventriloquising a quiet tune with a closed beak. They were bred to be cartoonishly yellow, bright blue, or just plain white. Some breeds would be stretched, others stooped like vultures, while others still sported goofy “bowl-cuts.”

In the late 19th century, following a series of deadly, carbon-monoxide-related mining accidents in Britain, it was proposed that some small animals be carried by miners going about their work. By the turn of the 20th century, canaries were carried into coal mines, trapped in a cage, hung at the miner’s hip. Their job was to detect poisonous gases like carbon-monoxide, exhibiting signs of distress before a person would feel any symptoms — acting as an early warning system for miners.

By 1981, “electronic noses” — digital gas detectors — had become common and reliable, and the British government began phasing out the use of canaries in mines. In Britain, the use of canaries in coal mines was officially outlawed in 1986.

-

Omlet – Guide to Canary Song Training

Strain differences in hearing in song canaries by Jane A. Brown, et al.

Pet Corner – Singing Canary Breeds

MAP Ecology – National Canary Contest in Essaouira, Morocco

Domestication of the canary, Serinus canaria - the change from green to yellow ·by T. R. BIRKHEAD, et al.

PocketBook – Canary domestication

Gale Review – Canaries in the coal mine history

Gale Primary Source 1 – Historical article on mining safety and canaries

Gale Primary Source 2 – Coal mining and gas detection account

Gale Primary Source 3 – Industrial safety source on miners and canaries

Gale Primary Source 4 – Report on mining practices and animal use

Smithsonian Magazine – History of canaries in coal mines

Britannica – Mine Gas

A Survey on Gas Sensing Technology by Xiao Liu, et al.

Museum Crush – Canary resuscitation devices in mining

Birds of the World– European serin

Mining Heritage – Role of pit ponies in coal mining

Gale Primary Source – Mining report mentioning pit ponies

Mining History Association – History of pit ponies in the U.S.

Hansard (UK Parliament) – Parliamentary debate on pit pony conditions

National Institute for Minamata Disease (Japan) – Environmental monitoring and sentinel species

The Conversation – Birds as environmental indicators

Mussels as biological indicators of pollution by A. Viarengo and L. Canesi.

ZME Science – Mussels Reveal Water Plant Diversity in Poznań

WHOI Oceanus – Ocean Acidification: A Risky Shell Game

-

Cover Photo (© Volker Hesse / Macaulay Library)

Text Photo #01 (© Nathaniel Dargue / Macaulay Library)

Text Photo #02 (© ArnoldPlaton / Wikimedia Commons)

Text Photo #03 (© Atlee Hargis / Wikimedia Commons)

Gallery #01 (© House, C. A.; St. John, Claude.; Weston, G. E., © House, C. A.; St. John, Claude.; Weston, G. E., © House, C. A.; St. John, Claude.; Weston, G. E., © Blakston, W. A.; Swaysland, W.; Wiener, August F., © Blakston, W. A. Swaysland, W Wiener., August F., © Blakston, W. A.; Swaysland, W.; Wiener, August F., and © Blakston, W. A.; Swaysland, W.; Wiener, August F. / Wikimedia Commons)

Text Photo #04 (© George McCaa, U.S. Bureau of Mines / Smithsonian Magazine)

Text Photo #05 (© Lebrecht Music & Arts / Alamy)

Text Photo #06 (© Mirrorpix / Colaborador / Getty Images)

Text Photo #07 (© Brittany Janette / YouTube / University of Saskatchewan)

Text Photo #08 (Julia Pełka (Gruba Kaáka))

Text Photo #09 (© The Ocean Agency)

Gallery #02 (Charles H. Smith / Wikimedia Commons, © Taronga Zoo, © AP Photo / Juan Karita, and © Pascale van Rooij / iNaturalist)

Gallery #03 (© Marc FASOL, © Nigel Voaden, © Yeray Seminario, © Julia Moning, © Andrés Rojas Sánchez, © Volker Hesse, and © Volker Hesse / Macaulay Library)

Text Photo #10 (Heinrich Börner / Wikimedia Commons)

Text Photo #11 (© Science and Industry Museum)

Slide Photo #01 (© Christoph Moning / iNaturalist)

Slide Photo #02 (© Martin Flack / Macaulay Library)

Slide Photo #03 (© Lars Petersson | My World of Bird Photography / Macaulay Library)