White-rumped Vulture

Gyps bengalensis

The white-rumped vulture was once India’s most common vulture — and perhaps the most numerous large bird of prey in the world. But between the mid-1990s and 2006, its population plummeted by 99.9%, and it’s now considered critically endangered.

Vulture Crisis

In the 1990s, vultures across northern India began to drop dead.

Where once these macabre birds circled above every village and garbage heap, none were longer seen. Vultures dwindled by over 90% as the die-off spread across the subcontinent. Not since the extinction of the passenger pigeon had a bird population collapsed at such speed and scale.¹

Then people began to die too.

Rotting carcasses contaminated rivers, and pathogens seeped into the water supply. Feral dogs carried leptospirosis and ran wild with rabies, spreading diseases from dog to dog to human. In districts where vultures once thrived, and were now all but absent, the human death rate rose by over 4%. Over the course of five pestilent years, half a million people are estimated to have died as a consequence of this vulture crisis.

The Commonest of All the Vultures of India

The species hit hardest was the white-rumped vulture; the smallest of the bare-necked, griffon vultures, but a large bird — up to 85 centimetres (2.8 ft) tall — nonetheless, named for a distinguishing white patch of feathers on its lower back.

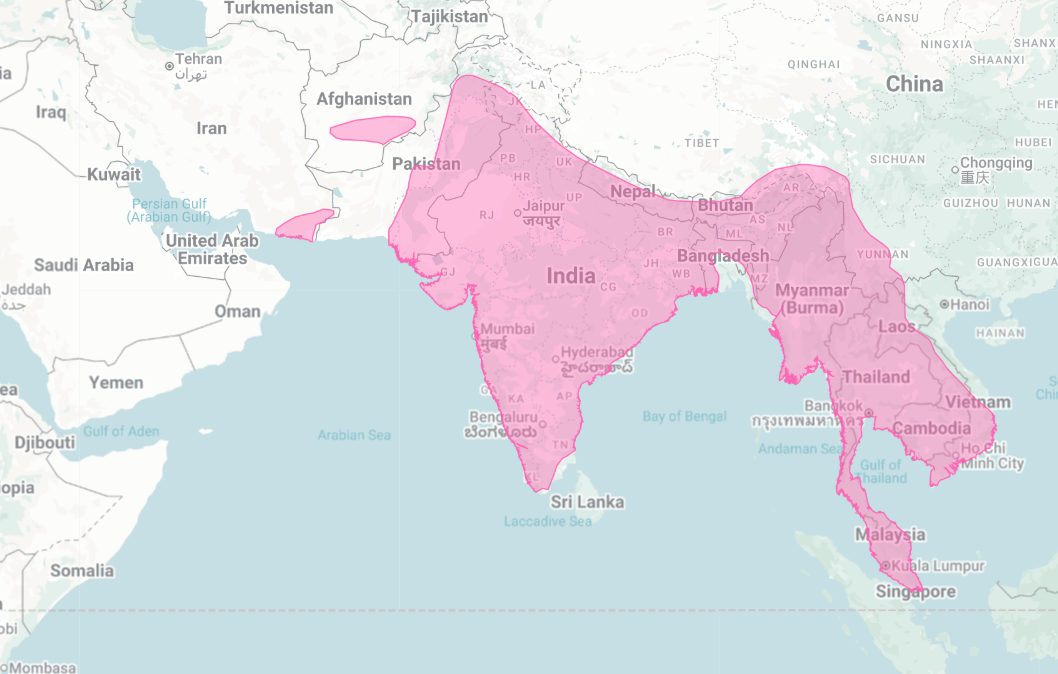

Prior to the 1990s, this vulture was thought to be the most numerous large bird of prey in the world — its range extending from Pakistan to southern India, to Southeast Asia and China. Naturalists in India noted it's great abundance, writing in the 19th century that the white-rumped vulture “is the most common vulture of India, and is found in immense numbers all over the country" and in the 20th century, that it continues to be "the commonest of all the vultures of India, and must be familiar to those who have visited the Towers of Silence in Bombay.”²

White-rumped vultures could be spotted wheeling above Kolkata in great numbers, their open wings spanning over 2 metres (6.6 ft). One could see "hundreds of nests" in a single grove — each some 90 cm (3 ft) in diameter — with more than 15 nests per tree. Vulture couples would build their nests in the wide canopies of wild banyan and peepul trees, in cultivated orchards and city parks. The big birds were so abundant that people considered them a nuisance: their caustic excrement carpeted the palms of orchards and plantations, and their high-flying (up to 2,740 metres or 9,000 feet) made them a collision risk for rising and landing aeroplanes.³

Then, beginning quite suddenly in the mid-1990s, the population of white-rumped vultures — that "commonest of all the vultures of India" — started to decline. From India and its nearby countries, 99.9% of the population would die off.

The Killer Painkiller

By the mid-1990s, the three most common vulture species in India — the Indian, slender-billed, and white-rumped vultures — would fall from a combined population of ~50 million to near zero. What caused the precipitous decline? Did some new, terrible disease arise, causing a vulture epidemic? Were the vultures targeted and purged for the inconveniences they caused us, as the passenger pigeon was?

The vultures of India were dropping dead of organ failure — specifically, their kidneys were being destroyed — and it was the fault of humans. But this was no disease, and neither was it a deliberate attack. The seemingly innocuous culprit behind the crisis was a painkiller called diclofenac. But how was a veterinary drug, used primarily to treat inflammation, getting into the systems of wild vultures?

India has long had the largest bovine — cattle and buffalo — population of any country in the world, with some 288.8 million bovines in 1992. But India is also a majority Hindu country where cattle aren't consumed on account of their sacred status, and so the majority of cows are used for the production of milk and manure, or as draught animals that carry loads or plough fields. Since most cattle aren't slaughtered for meat, many are allowed to live out their lives until they die of illness or old age. Their bodies are then left for scavengers, like vultures.

When the patent for diclofenac was lifted in the early 1990s, the drug became readily available and cheap, and India's massive cattle population was liberally dosed with the drug. When a cow with diclofenac in its system dies, traces of the drug remain in its carcass. While diclofenac works to decrease inflammation in mammals, when eaten by birds like vultures, even small doses lead to kidney failure and, ultimately, death.

The Disorderly Committee for Waste Disposal

We've come up with many colourful names for different groups of animals: a prickle of porcupines, a crash of rhinoceroses, a flamboyance of flamingos, an embarrassment of pandas. Usually, the name reflects the nature of the animals.

Vultures are associated with pestilence and death. When they gather, it's often for a gruesome feeding frenzy with blood and guts aplenty. You might reasonably expect their gatherings to be called something like a requiem or a stench of vultures. Instead, they are most commonly known as a committee. The name is more fitting than it may seem, for the vultures gather to do a job that few other animals could manage.

That's not to say they are a smoothly functioning committee.

One by one, vultures descend upon a carcass. They begin by pecking at the body, finding their way inside via the holes (eyes, mouth, or anus). More and more vultures gather — a single carcass may be the venue for over 70 vultures — and the feast escalates. The stomach contents spill out, and the entrails are dragged around like bloody party streamers. The vultures squabble over the best bits: they hiss, kick, and flap their wings at one another. And they gorge. Given the chance, a white-rumped vulture will consume so much carrion that it won't be able to fly after its meal. A committee of vultures can strip a cow to the bones in 40 minutes. It's certainly not pretty, but it is very efficient.

White-rumped vultures feed almost entirely on the bodies of dead animals. They don't care if their food is fresh or putrid.⁴ They don't care if it's found dead on a road or scavenged from a dumpster — they especially like slaughterhouse dumpsters. They don't care if it comes from a fish (they're known to scavenge at dried-up lakes), a fowl (they'll even eat dead vultures), or a furred beast. In India, the white-rumped vulture's diet is mostly the remains of cows and humans.

In most Western cultures, the idea of being consumed by scavengers is repugnant. "Leave him for the vultures," we say of a defeated enemy. Afford his corpse no respect. Strip him of any dignity, even in death, as the scavengers will strip his flesh.

The same sentiment isn't shared across the globe, however. In parts of Mongolia, China, Tibet, and India, some cultures practice a ritual known as Sky Burial. In landscapes that lack the trees for building a pyre, with ground too rocky and hard to dig a grave, the bodies of loved ones are brought to the hilltops and their physical forms are given back to the natural world by way of consumption by scavengers. Far from insulting, disposing of a body in this way is compassionate and respectful. It is also very practical.

A dead body, whether human or cow, quickly becomes a breeding ground for pathogens. While farmers across India may not haul their deceased cattle to the tops of hills, they have historically relied on scavengers to "clean up" their dead livestock. And, despite their chaotic committees, no creature is as proficient a scavenger as a vulture. Not only can a group of them swiftly strip a carcass clean, but all of the pathogens germinating on it and inside it are destroyed by the strongest stomachs in the animal kingdom. Salmonella, botulism, anthrax — none of the bacteria responsible are coming out the other end of a vulture. A vulture's stomach is a dead end for diseases. It feels wrong to call vultures cleanly; their naked heads buried deep in carrion, their feathers covered in gore. But they are the sanitisers and waste disposal workers. They are keystone species in their ecosystems.

When vultures all but disappeared from large parts of India, populations of other scavengers — feral dogs, crows, and rats — grew in their absence. They took up the job of undertaker, and they proved poor replacements. Stray dog populations increased, and with them, the prevalence of rabies. The stomachs of these scavengers simply weren't strong enough to kill all the harmful bacteria in carrion, so instead of sanitisers, they became spreaders of disease — with faecal bacteria in the water more than doubling during this time.

They also weren't nearly as fast as vultures. Bodies piled up in fields at the outskirts of cities, becoming great rotting dumps and mass incubators for disease. Some farmers disposed of their dead livestock in rivers, allowing disease to spread via waterways. The Indian government ordered tanneries to get rid of dead bodies using chemicals. They did so, and the agents used to dissolve the dead leached into the water supply. The rivers churned with toxins and disease. What began as a vulture crisis quickly became a national health crisis.⁵

Long-Deserved Praise

The use of diclofenac was banned in India in 2006,⁶ but the consequences of this one drug — the devastation of the country's vulture populations and the avoidable deaths of half a million people — haven't just gone away. Vultures in India now mostly exist around protected areas, where conservationists provision them with safe carrion at "vulture restaurants."

The red-headed vulture lost 91% of its population to the crisis, the Indian vulture 95%, and the slender-billed 99%. The white-rumped vulture, once the most common vulture in India and the most abundant large bird of prey in the world, was nearly wiped out.It once floated above cities and towns, crowded trees with nests, and squabbled over the dead. Today, it is considered critically endangered. Once in the tens of millions, its global population is now estimated to total just 6,000 to 9,000 individuals.

I wish there were a happy note to end this story. But the aftermath of a great catastrophe is rarely a fast rally. More often, it’s a slow, steady climb toward recovery. And sometimes, the only consolation is a lesson learned. When it comes to vultures, despite their grim reputation, death proliferates not in their presence but in their absence. It may have taken a crisis to fully appreciate their importance, but now their services are starkly clear. It's not too late to aid in their recovery. And it's not too late to give vultures, not disdain or disgust, but the praise they've so long deserved.

¹ When Europeans first arrived in America, between 3 and 5 billion passenger pigeons flew across the continent in endless flocks. By the early 1900s, however, no wild passenger pigeons were found in the wild — brought low by overhunting and habitat loss. On the 1st of September, 1914, a passenger pigeon named Martha died in captivity, and no living passenger pigeon has been seen since. From billions in the mid-1800s to zero less than a century later.

² The first quote comes from the English physician, zoologist, and botanist Thomas C. Jerdon (1811 – 1872), who was the first to describe many species of birds in India. The second quote is from the English ornithologist Hugh Whistler (1889 – 1943), who likewise studied and described the avifauna of India and wrote one of the first field guides to the country's birds. The "Towers of Silence" Whistler refers to are circular stone platforms used in Zoroastrian funerary rites, where the dead were laid out to be consumed by vultures and other carrion birds.

³ In India, in the 80s and 90s, vultures contributed to 25% of bird-plane strikes.

⁴ Contrary to popular belief, if a vulture is given a choice, its preference is not rotted meat — a body left to ripen a day or two in the sun is ideal, but a carcass can become too putrefied even for the palate of a vulture. But this is usually a non-issue, given that the exceptional eyesight of old world vultures can spot an expired creature on the ground even as they soar on their thermals thousands of metres in the air. On the other hand, if the body is too fresh or the hide too thick, vultures may have to wait upon slower, but strong-jawed scavengers to arrive and open up the banquet. In India, a carcass will often be attended by a feasting crowd of vultures, jackals, and storks.

⁵ In districts where vultures were never very numerous, the death rate remained unchanged at around 0.9%. In districts that lost their vultures, the death rate increased by 4.7% on average, amounting to over 100,000 additional deaths a year.

⁶ Other countries like Pakistan, Nepal, and Bangladesh banned the drug between 2006 and 2010. Despite the ban, diclofenac continued to be sold illegally for some time afterwards.

Where Does It Live?

⛰️ Open plains and country, often near villages, towns and cities.

📍 Much of India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, and Southeast Asia.

‘Critically Endangered’ as of 07 Jul, 2021.

-

Size // Medium

Length // 76 - 93 cm (30 - 37 inches)

Wingspan // 205 - 220 cm (6.75 - 7.2 feet)

Weight // 3.5 - 6 kg (7.7 - 13.2 lbs)

-

Activity: Diurnal ☀️

Lifestyle: Mostly solitary 👤

Lifespan: Up to 17 years

Diet: Carnivore

Favorite Food: Carrion ☠

-

Class: Aves

Order: Accipitriformes

Family: Accipitridae

Genus: Gyps

Species: G. bengalensis

-

The vulture population of India once exceeded 50 million. The most common species, the white-rumped vulture, could be seen circling towns and cities and crowding tree groves in the hundreds — with more than 15 nests in a single tree.

In the mid-1990s, India's vulture species began to die out. Most species declined by 90%. The white-rumped vulture lost 99.9% of its population, almost completely disappearing.

The cause was a painkiller called diclofenac, whose patent had expired in India in the early 1990s and, as a result, became cheap and widely used. Given to cattle, it reduced inflammation. But when eaten by vultures — who were often responsible for "cleaning up" the bodies of dead cattle — it caused kidney failure and death.

What followed was a health crisis. Rotting carcasses contaminated rivers, and pathogens seeped into the water supply. Feral dogs ran wild with rabies. In districts where vultures were never very numerous, the death rate remained unchanged at around 0.9%. In districts that lost their vultures, the death rate increased by 4.7% on average, amounting to over 100,000 additional deaths a year.

Vultures have some of the strongest stomachs in the animal kingdom — preventing the spread of salmonella, botulism, anthrax, and rabies.

Once “the most common vulture of India” and likely the most numerous large bird of prey in the world, the white-rumped vulture has declined to a critically endangered species numbering just 6,000 to 9,000 individuals.

-

Cornell Lab: Birds of the World

San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance

BBC News – India's vultures nearly vanished. They're slowly coming back

Science – Loss of India’s vultures may have led to deaths of half a million people

Indian vultures on the brink of extinction by Dr. A. K. SINGH.

CBS News – How dying vultures in India are linked to a surge in human deaths

Science Alert – Shift in India's Vulture Population Linked to Half a Million Human Deaths

The Indian Express – Between the headlines: In 20 yrs, more poultry than cattle

-

Cover Photo (© Aseem Kothiala / Macaulay Library)

Text Photo #01 (© Ali Usman Baig / Macaulay Library)

Text Photo #02 (© Neenad Abhang / Macaulay Library)

Text Photo #03 (© Meinzahn / iStock)

Text Photo #04 (© Rotem Avisar / Macaulay Library)

Text Photo #05 (© Nishant Sharma Parajuli / Macaulay Library)

Text Photo #06 (© Gobind Sagar Bhardwaj / Macaulay Library)

Text Photo #07 (Smith Bennett / Wikimedia Commons)

Slide Photo #01 (© Deepak Budhathoki 🦉 / Macaulay Library

Slide Photo #02 (© Sachin Kumar Bhagat / Macaulay Library

Slide Photo #03 (© Roundglass Sustain)

Slide Photo #04 (© Arpit Bansal / Macaulay Library)

Slide Photo #05 (© Ayuwat Jearwattanakanok / Macaulay Library)