“The change from plants to animals…is gradual…”

“The change from plants to animals…is gradual… For a person might question to which of these classes some marine objects belong; for many of them are attached to the rock, and perish as soon as they are separated from it. The pinnae are attached to the rocks, the solens cannot live after they are taken away from their localities; and, on the whole, all the testacea resemble plants, if we compare them with locomotive animals. Some of them appear to have no sensation; in others it is very dull. The body of some of them is naturally fleshy, as of those which are called tethya; and the acalephe and the sponge entirely resemble plants; the progress is always gradual by which one appears to have more life and motion than another.”

What exactly is an animal?

You could define an animal as any living thing within the kingdom Animalia, as opposed to those belonging to the other kingdoms of life: the Bacteria, Fungi, Plantae, etc.

That would be true, but it’s also just substituting a label for an actual explanation; defining animals by calling them animals — a circular answer that puts the cart before the still-undefined horse, if you will. It begs the question: what delineates a member of the animal kingdom as opposed to, say, a member of the plant kingdom?

The differences between a plant and an animal seem obvious when comparing, for instance, an orchid to an antelope. But the lines are not always so clear-cut. There is a no-man's-land between the two kingdoms. This grey-zone was identified more than 2,300 years ago by the Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle, who wrote in his History of Animals that “the change from plants to animals…is gradual…”

Aristotle, the “Father of Zoology,” is credited as the first person to systematically study, observe, and classify animals. And as he classified over 500 animals — by their physiologies, behaviours, habitats, dispositions — he noticed that the traits of certain animal groups blurred into those of other kinds of life, namely plants.

Plants vs. Animals

By which traits do we divide plant from animal, say an orchid and antelope, into their respective kingdoms?

At the most basic level, both of them are multicellular — unlike bacteria and archaea — but the compositions of their cells are different: the orchid’s cells have rigid cell walls and organelles called chloroplasts that perform photosynthesis, while the antelope’s cells lack those features, and thus are more irregular in shape and incapable of photosynthesising.

That leads us to energy.

Most plants — as well as algae, which belong to various different kingdoms — get their energy from the sun. Most animals, in contrast, get their energy from other living organisms; be they plants, fungi, or other animals.

“Wherever the sun strikes the plants are more frequent, and superior, and more delicate,” writes Aristotle. The orchid spreads its leaves towards the light. The chloroplasts in its cells capture photons and use their energy to split water (H₂O) molecules absorbed through its roots, releasing oxygen (O₂) into the air. The sunlight’s energy is temporarily stored in special energy-carrying molecules, which use the hydrogen from water to convert carbon dioxide (CO₂) from the air into usable sugars (known as photosynthates).

The antelope, meanwhile, eats those plants, digests their sugars, and uses oxygen (O₂) to release their energy, while producing carbon dioxide (CO₂) as a byproduct — a chemical “mirror image” to plant cellular respiration (though the processes use very different enzymes and mechanisms). Carnivorous animals, in turn, obtain energy by digesting the fats, proteins, and carbohydrates of other animals’ tissues. Or, in Aristotle’s words “sheep fatten on green shoots, vetches, and all kinds of grass…”¹ and “the lion…devours its food greedily, and swallows large pieces without dividing them…[and] in his manner of feeding is very cruel.”

To find food — to find anything — an animal needs to sense.

Chapter eight of History of Animals is about the senses, “for they are not alike in all, but some [animals] have all the senses, and some fewer. They are mostly five in number; seeing, hearing, smelling, taste, touch.”

Jumping spiders have acute central eyes that can see movements and colours with exceptional precision, given their tiny size.

The large, grooved ears of bats allow them to hear the echoes of their own ultrasonic screams.

Kiwis are the only birds to have their nostrils at the tips of their beaks, which they use to poke and prod, and smell anything hiding beneath the soil.

Catfish are “swimming tongues” with tastebuds spread across their skin, allowing them to “taste” the water all around them.

Star-nosed moles have ultra-sensitive nose organs packed with over 25,000 sensory receptors that can identify prey in milliseconds through touch alone.

“…and besides these,” writes Aristotle, “there are none peculiar to any creatures.”

But, unbeknownst to Aristotle, there are in fact senses quite “peculiar” to a few special species.

These senses can be found in knife- and elephantfishes, who generate weak electric fields around their bodies, and can sense when those fields become distorted by objects or other organisms in their surroundings. And in sea turtles and pigeons, who use a still-mysterious mechanism to sense the Earth’s magnetic field. (Notice how there are no words like “see” or “hear” ascribed to these senses in the human lexicon, as these are senses we humans don’t have.)

All of these incoming stimuli — light and sound waves, chemicals, electric charges, and magnetic fields — can only be detected by specially-adapted sensory cells. They are then transmitted along nerves to be interpreted by a central nervous system, or brain. The resulting decision is sent via nerves again, this time from the brain to various muscles in the body. Then? Action.

The jumping spider springs at a fly.

The bat swoops to avoid a branch.

The kiwi pecks the soil and pulls up a grub.

The catfish swims towards a drowned carcass.

The star-nosed mole flicks a worm into its mouth.

The knifefish swerves to avoid an incoming predator.

The sea turtle adjusts course to reach a destination thousands of miles away.

-

But not every action requires processing by the brain.

Many fish exhibit what’s known as the ‘C-start’ reflex. When a fish senses a sudden threat — such as vibrations in the water — specialized neurons in its spinal cord fire immediately, and the fish’s body bends into a C-shape (hence the name). The fish then straightens its body and thrusts off, propelling itself rapidly away from the threat. The entire sequence takes just tens of milliseconds, much faster than if the signal had to be processed by the brain.

This reflex allows fish to swiftly escape predators, but, because it happens so quickly, the fish’s brain can’t intervene to stop the C-start response once it’s been triggered. And so this reflex meant to reduce predation has, in certain cases, made fish more vulnerable.

Aristotle describes “serpents” as “illiberal and crafty.” In the latter, he is not wrong.

The tentacled snake is an aquatic species from Southeast Asia, named for a pair of “tentacles” at the front of its head. No other snake we know of has the same kind of paired, flexible, and sensitive appendages on its snout, and the tentacled snake uses them for an appropriately unique purpose: its tentacles are full of mechanoreceptors that can detect movements in the water.

Just as we humans combine information from sight and sound to create a mental picture of the things going on around us, the tentacled snake’s brain incorporates visual data from its eyes with touch data from its tentacles to sense its watery world. And it uses that information to find, trick, and devour fish.

The tentacled snake is an ambush predator that rarely leaves the water; its dark-striped and mottled body resembles a large branch or strip of bark floating amidst underwater foliage. When a fish swims near, rather than strike outright, the tentacled snake swishes a length of its rear body, sending a ripple of water towards the fish, startling it. The fish's reflexes take over — the C-start reflex, specifically — and the fish bends and shoots off in the opposite direction from the disturbance, right into the snake’s waiting jaws.

Is this automatic reflex, often life-saving and occasionally fatal, really that different from how plants respond to their environment, except perhaps in speed? There’s no processing going on in the fish’s brain here, no decision making. There’s just a stimulus and response.

Plants can also sense, in their own ways. They’re able to detect the presence and direction of light, the mechanical disturbances of wind or a browsing animal, and the chemistry of the soil and air. And this sensing can lead to a response: a flower turns and opens towards the sun, a vine coils tightly after brushing against a branch, a plant’s stomata closes when water becomes scarce.

Compared to most animals, however, these actions are certainly slow.

-

But what about the Venus fly trap, you may be asking? It is certainly an exceptional plant in the speed of its response to stimuli, but it also illustrates the underlying differences between the two kingdoms.

Inside each trap are three to four stiff trigger hairs. When an insect lands in the trap and touches one hair, causing it to bend…nothing happens. But if it touches another hair, or the same one repeatedly in a span of less than 5 seconds or so, the trap snaps shut.

Mechanical stimulation of the hairs activates electrical signals, which then trigger a rapid shift in pressure within the cells of the leaf, causing it to fold inward in a fraction of a second. In this sense, the flytrap does something very animal-like — it uses electricity to coordinate movement — yet it does so without nerves, without synapses, and without anything resembling a brain.

The Venus fly trap's hunting “strategy” could be called reflex-like, not unlike the C-start of fish, as it’s triggered automatically by specific circumstances with no input from any kind of central nervous system. But the term sort of loses its meaning in plants, as they have no nervous systems, central or otherwise, to produce any non-reflexual behaviour.

“A Venus Flytrap (Dionaea muscipula) closing after one of the trigger hairs is stimulated.”

© Mnolf / Wikimedia Commons

Both plants and animals use receptors to detect stimuli and convert those stimuli into electrochemical signals. However, in most plants (save the Venus fly trap and its trigger hairs), receptors are distributed across their tissues rather than concentrated in particular sensory organs — like eyes or ears in animals.

The crucial distinction between plants and animals is not speed alone, but organisation and the type of movement that organisation facilitates. Animals evolved nervous systems that transmit signals rapidly and coordinate muscles capable of immediate, reversible movement. A fish’s escape reflex occurs in milliseconds and propels its entire body through space.

Plants, by contrast, have no nervous systems, no discrete sensory organs, and no muscles. Where animals respond by moving themselves through the world, plants respond either by modifying themselves — altering their form or physiology through growth — or through limited local movements; that is, a leaf may curl up or a fly trap may close, but the entire plant doesn’t move.

Both kingdoms sense and respond, but while animals have the ability to convert sensation into coordinated, whole-body movement, plants convert sensation into growth, modulation, and localised movement.

“Marine Objects”

So we have our descriptive definition of an animal.

An animal is a multicellular organism, whose cells lack walls and chloroplasts, that obtains energy from other living things, senses its surroundings, and responds to those stimuli by taking action — sometimes deliberate and sometimes reflexive — often through whole-body movement.

What happens, then, when we encounter an organism that can scarcely sense, barely move, and has no central nervous system? Is it a plant? Well, it doesn’t photosynthesise, its cells contain no chloroplasts, rather it gets energy by ingesting bits of other living things. Or what about an organism that is rooted in place and can photosynthesis, but also uses fast-acting muscles to catch and consume other organisms? Plant or animal?

It is where life first evolved on Earth, in the salty liquid medium of the oceans, among clams and jellyfish, corals and sponges, that we find its kingdoms to be the least defined.

“A person might question to which of these classes some marine objects belong.”

———

“On the whole,” writes Aristotle, “all the testacea resemble plants, if we compare them with locomotive animals.” Aristotle describes testacea as “animals which have their internal parts fleshy, and their external parts hard, brittle, and fragile, but not liable to contusion,” giving snails and oysters as two examples. Many of the animals he placed into this category we’d today call shelled molluscs.²

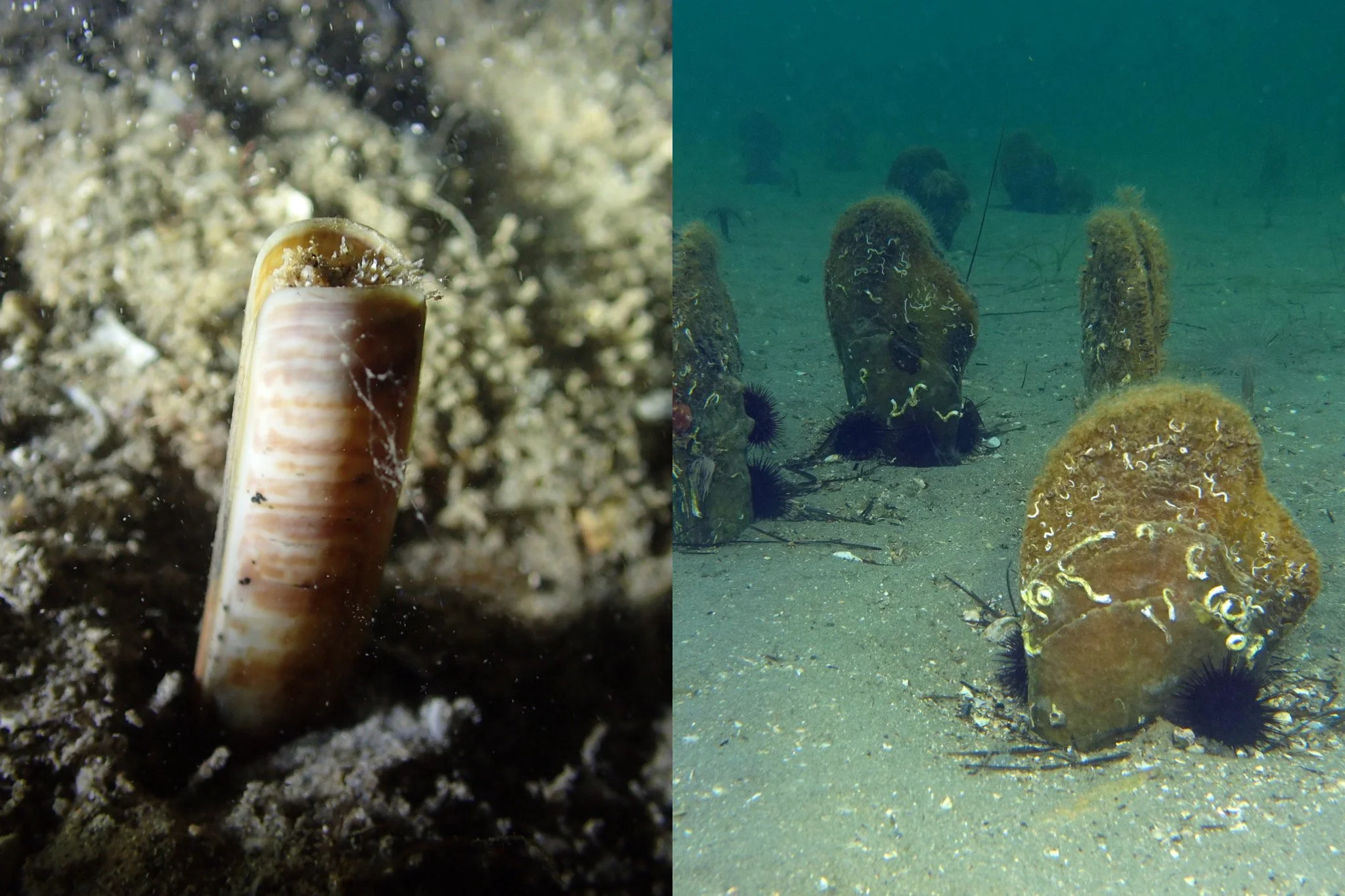

An example are the “solens,” or razor clams (members of the family Solenidae); bivalved molluscs with long, narrow and slightly curved shells that can be found standing upright in sediment, anchored down by a muscular foot that holds them in place. If threatened, however, a razor clam can pull its foot into its shell and swiftly bury itself beneath the sand or mud.

The “pinnae,” today known as pen shells (family Pinnidae), are likewise bivalves, although their shells are long and triangular. Like razor clams, pen shells can also be found standing vertically in soft sediment or wedged among rocks, with their narrow ends buried. Pen shells, however, “are attached to the rocks”; permanently anchored to their surface by fibrous byssal threads, not unlike the roots of a plant.

A southern razor clam (left) and noble pen shells (right).

It's easy to see why Aristotle considers these “marine objects” as bordering on the realm of plants, especially the rooted pen shells. Like a plant, these bivalves “cannot live after they are taken away from their localities,” requiring water and a substrate to survive, and when comparing these sedentary creatures to the likes of swooping bats, leaping spiders, and swimming catfish, they do indeed appear to be more akin to plants.³

In De Anima (On the soul), Aristotle says that “self-nutrition,” or the ability to obtain energy “is the originative power, the possession of which leads us to speak of things as living at all, but it is the possession of sensation that leads us for the first time to speak of living things as animals; for even those beings which possess no power of local movement but do possess the power of sensation we call animals and not merely living things.”

What kind of “powers of sensation” do these sedentary bivalves possess? According to Aristotle, “some of them appear to have no sensation; in others it is very dull.”

On the senses of testacea, he explains that “the solens [razor clams], if a person touch them, appear to retract themselves, and try to escape when they see an instrument approaching them, for a small portion of them is beyond the shell, the remainder as it were in a retreat; the pectens [scallops], also, if a finger is brought near them, open and shut themselves as if they could see.”

Indeed, most bivalves are known to have some type of eye, ranging from the sophisticated, mirrored eyes of scallops to simple, light-sensing cells that can only differentiate between light and shadow. On the whole, however, bivalves appear to rely mostly on mechanoreceptors — as Aristotle states, “the sense of touch belongs to all animals.”

He goes on to explain that the “testacea have the senses of smelling and tasting” too, and that “this is plain from the baits used, as those for the purpuræ; for this creature is caught with putrid substances, and will be attracted from a great distance to such baits, as if by the sense of smell. It is evident from what follows that they possess the sense of taste; for whatever they select by smell, they all love to taste.”

The senses of smell and taste are both considered chemoreception, or the detection of chemicals, differing only in how and where the chemical signals are detected. Aristotle is saying that the purpuræ — likely referring to a purple-dye-producing mollusc (perhaps one in the genus Murex or Hexaplex) — is attracted to putrid bait, proving that it can smell; and if it can smell, and it is attracted to the smelly bait, it must also enjoy how it tastes, for “all animals with mouths receive pain or pleasure from the contact of food.”

A banded dye-murex (Hexaplex trunculus).

“…throughout the entire animal scale,” writes Aristotle, “ there is a graduated differentiation in amount of vitality and in capacity for motion.” And, in general, it seems the less an animal can do — that is, the actions it’s capable of taking — the less senses it will be found to have.

A murex snail, for instance, moves to find food, actively pursuing its prey. Razor clams and pen shells, on the other hand, are sedentary filter feeders that draw in water, filter out the edible particles, and then expel the filtered water. Their senses are used primarily in response to threats: to close up and/or retreat down into the sand — uniform responses that don’t require particularly detailed recognition of their surroundings.

———

Moving away from the shelled testacea, Aristotle describes marine creatures whose bodies are “naturally fleshy, as of those which are called tethya” and, of those fleshy marine creatures, he says, “the acalephe and the sponge entirely resemble plants.”

The acalephe he’s referring to are likely sea anemones and jellyfish.

Top: Agulhas sea nettle, common moon jelly, and barrel jelly

Bottom: Red-striped anemone, green snakelock anemone, and cryptic burrowing anemone

© Callum Evans, © Rita Jansen, © xavi salvador costa, © Tony Wills, © imogenisunderwater, and © Josh Houston / iNaturalist

“The class acalephe is peculiar,” he writes, “it adheres to rocks like some of the testacea, but at times it is washed off. It is not covered with a shell, but its whole body is fleshy…”

It may seem odd to group these two kinds of animals together — one mostly rooted and unmoving, the other free-floating along the ocean currents — but they are actually close relatives, both in the phylum Cnidaria. Evidence of their relationship can be seen in the distinctive features they share, most notably, perhaps, in their stinging tentacles.

Aristotle writes how an acalephe “seizes upon the hand that touches it, and it holds fast, like the polypus [octopus] does with its tentacula, so as to make the flesh swell up.”

Whether swaying upwards as in anemones or trailing aft as in jellyfish, the tentacles of cnidarians are covered in specialised stinging cells (called cnidocytes), and each cell contains microscopic organelles (called nematocysts) that act like tiny harpoons filled with venom. These stinging cells could well be called biological "micro-machines" — activated by mechanical and chemical means, fired out using pressure differentials — and they are fairly complex parts of otherwise quite simple creatures.

Aristotle calls the acalephe “sensitive” and notes how “in summer time they perish, for they become soft; if they are touched they soon melt down…” Indeed, jellyfish especially are famous for their simple compositions, with over 95% of their body mass made up of water. Neither jellyfish nor sea anemones have hard skeletons, and, inside, you’ll find no complex organs like a heart or brain. To Aristotle, these organisms may well have looked like odd oceanic plants, whether tethered or free-floating. What Aristotle could not have known, however, is that beneath their squishy tissues lay a nervous system — not centralised in a brain, but spread throughout the body in two diffuse nerve “nets.”

What kind of inputs do these nets have to handle?

The senses of sea anemones are limited much like those of plants: they can detect touch (mechanosensation), chemicals (chemoreception), light, and temperature changes, but no visual stimuli. Most jellyfish don’t quite have eyes either, but they do have light-sensitive cells around the rims of their bells (known as rhopalia), that can detect changes in light.⁴

The major difference between cnidarians and plants is how they can react to those stimuli. Sea anemones and jellyfish may seem completely passive — like the grass of the coral reef or dandelion seeds of the sea — but they do actually move, sometimes with purpose and speed.

Of their two nerve nets, sea anemones and jellyfish mostly use the larger, outer net to control their swimming. In jellyfish, this means activating muscles that expand and contract their bell, appearing as the rhythmic pulsing that slowly pushes a jellyfish along.

And anemones? Aren’t they sedentary animals?

They are when they’re comfortable, but when presented with unpleasant stimuli, such as poor environmental conditions or a predator, they can “uproot” and move. Most anemones do this by using their pedal disc, or the muscular base of their body, to slowly creep along a surface. However, some species known as ‘swimming anemones’ can detach completely and flex their bodies rapidly to move through the water at respectable speeds — hardly something you’d expect to see a plant do.

A swimming anemone escaping a sea star.

Another unplant-like behaviour is their “active feeding.”

Aristotle observed that an acalephe [anemone/jellyfish] has a “central mouth, and lives upon the rock, as well as upon shell-fish, and if any small fish falls in its way, it lays hold of it as with a hand, and if any eatable thing falls in its way it devours it. One species is free, and feeds upon anything it meets with, even pectens [scallops] and echini [sea urchins].”

If swimming anemones are like patrons at a buffet, actively going after their food, then most other sea anemones, as well as jellyfish, are like clientele at a conveyer belt sushi place, taking what comes along, yet still actively using their tentacles to sting, paralyse, and push their food into their central mouths — actions controlled by the smaller, inner nerve net.

All animals, after consuming food, need a way to dispose of waste products.

Aristotle remarks that a sea anomene/jellyfish appears “to have no visible excrement, and in this respect it resembles plants.”⁵ Although this may seem like a physiological footnote, he did not consider this faecal fact a minor detail. In most animals, digestion has a distinct beginning and end: food enters at one point and waste departs at another (what’s called a ‘through-gut’), leaving tangible evidence of the internal processing. Sea anemones and jellyfish, by contrast, possess a single opening; food enters and waste leaves through the same mouth/anus. With no distinct exit for excrement, there was nothing for Aristotle to observe as refuse, and little to suggest the kind of internal complexity he associated with a “complete” animal. It was for this reason, then, that he placed them among the “incomplete” animals — at the threshold of the plant kingdom.

But there are animals more dubious still, which even a modern scuba diver may mistake for submarine flora.

———

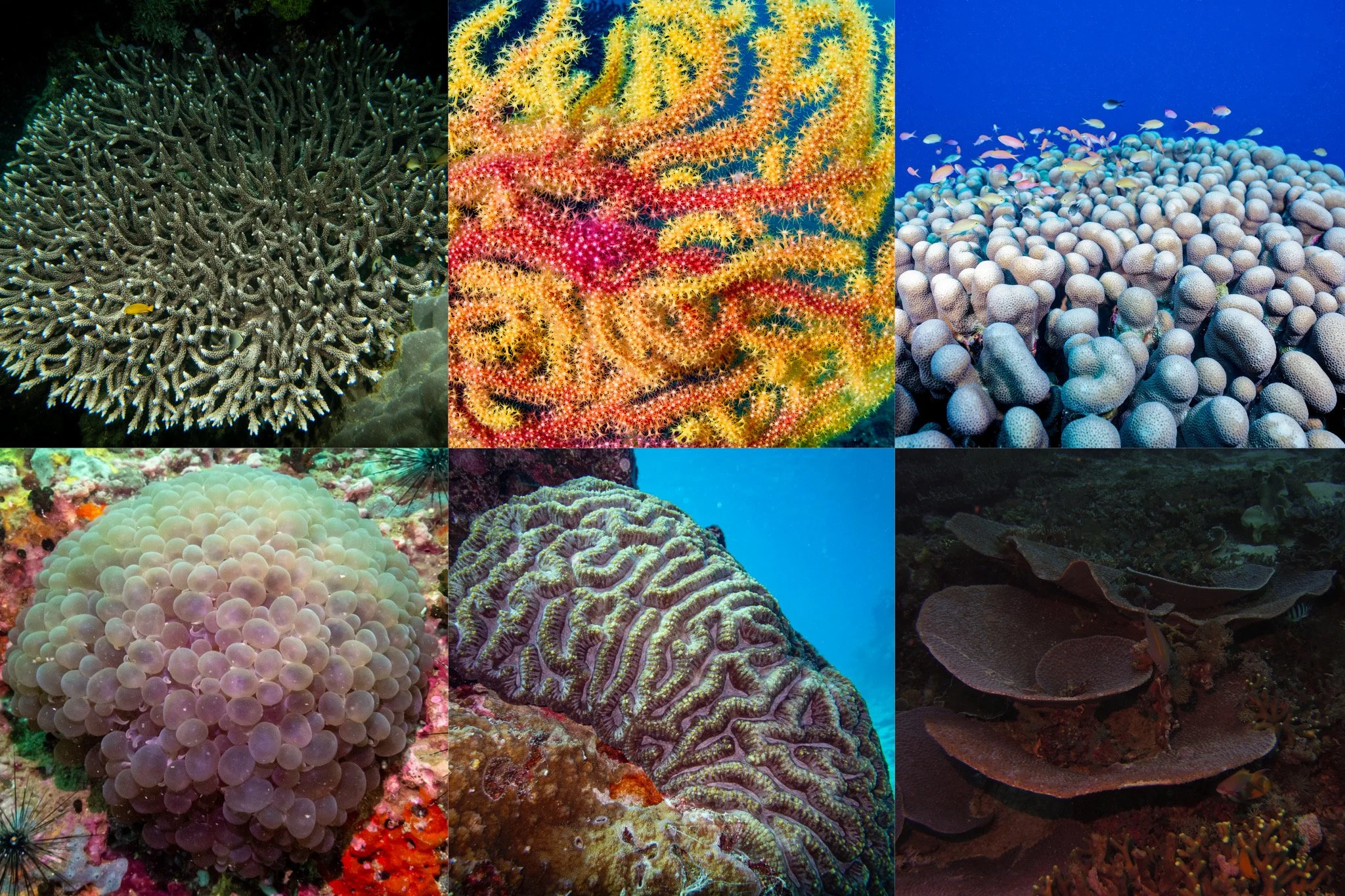

Coral reefs are often described as the “rainforests of the sea” for their great abundance and diversity of life. In a reef system, then, corals can be seen as the equivalent of trees. Some corals look very much like trees, with their repeatedly branching structures, while others splay out like handfans or stand as tall monoliths. Just as trees have their giants in the sequoias, the largest coral, the shoulderblade coral, surpasses the length of a blue whale. A forest would not be a forest without trees. Similarly, a coral reef is not a reef without corals, for their living forms give shelter to the rich reef life, while skeletons of their long-dead create the base the entire ecosystem rests upon.

Top left to bottom right: staghorn coral, violescent sea-whip, shoulderblade coral, bubble coral, open brain coral, and pagoda coral.

© Ingo Rogalla, © Jean-Paul Cassez, © David R,

© ig: underwater.logs, © Damien Brouste, and © mike_yan, / iNaturalist

An article from the July 1872 issue of The Popular Science Monthly evocatively describes the great architectural power of corals:

“Not only do they produce these exquisite arborescent forms, but they build gigantic structures with caverns, grottoes, and mighty arch-work, and raise rocky walls, which rival in extent and massive grandeur the noblest mountain scenery upon the land. Though these constructions proceed but slowly, yet in numbers that are inconceivable, and through ages that are incalculable these tiny beings have been engaged in the work of rock-manufacture, until they now rank with earthquakes, the rising and sinking of continents, and other stupendous agencies by which the crust of the globe has been shaped.”⁶

Corals are immobile and long-lived. They are great builders, “increased every year under their bark, like trees," (Linnaeus, 1761) as evidenced by their growth rings. By all appearances, they are very plant-like. But corals are not plants.

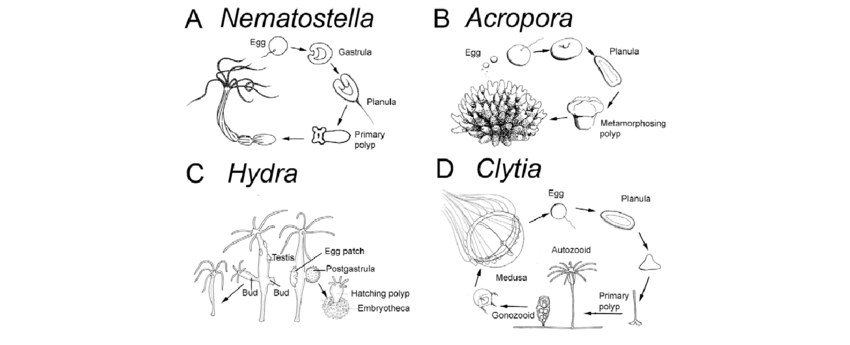

In 1758, Carl Linnaeus — the “father of taxonomy” — described the microscopic Hydra, naming it for its ability to regenerate lost parts, just as the mythical Greek monster can regenerate its many heads. Naturalists began calling the Hydra’s stationary and tentacled form a "polyp," since they thought its many writhing tentacles looked like a tiny octopus (which was known in Ancient Greek as the “polypus,” meaning “many-footed”).

The tiny Hydra, it turns out, is a relative of sea anemones and jellyfish. That shouldn’t come as too much of a surprise. After all, the Hydra’s “stalk” attaches to a surface while its “head” is covered in waving tentacles — it looks like a tiny, simplified sea anemone. However, and this may be surprising, the Hydra is actually a closer relative of jellyfish.

A brown hydra (Hydra oligactis).

It doesn’t much resemble the free-floating bell form of a jellyfish, known as the medusa — another cut from Greek myth — but it looks very similar to a jellyfish’s younger life stage; during which it settles down onto a surface to grow and, eventually, to pump out a bunch of genetically identical medusae into the water column. This small, sessile jellyfish form is known as the polyp stage. A sea anemone is essentially just a polyp that grows large and sexually matures, but never metamorphoses out of its polyp form.

If you took a bunch of tiny, permanent polyps and put them in the same place, rather than remaining solitary, they may come together to form a colony. They’ll start secreting calcium carbonate to build a rigid structure for themselves; this “skeleton” will branch and bulge and grow larger, and the polyps will multiply, the colony will grow. What you would get is a coral.

The life cycles of cnidarians.

(A) Nematostella sea anemones (B) Acropora stony corals (C) Hydra (D) Clytia jellyfish

All the way up until the 18th century, there was still apprehension about categorising these tiny, soft, and simple polyps as animals.

“To ascribe to "poor, little, helpless, jelly-like animals" the skill and power necessary to build such stately and beautiful structures, looked like a wanton appeal to human credulity, and the point was hence warmly controverted. Linnaeus, however, proposed a compromise. He would admit the animal, but would not deny the vegetable. He therefore assumed that these little toilers of the sea were of an intermediate nature, and named them zoophytes, animal-plants” — giving name to a concept Aristotle pondered some 2,000 years earlier.

“But the coral-polype is now known to be as truly an animal as a cat or a dog. The apparent flower is a little sac-like creature, and the wreath of colored petals its arms or tentacles. These are arranged around its circular mouth to seize and draw in the food upon which it lives and grows, while the structures which it produces are not perishable wood but enduring stone.” (Lewis, 1872)

Where do the coral polyps get the energy to collectively undertake such constructions? Like anemones, these tiny polyps use their tentacles and stinging cells to capture plankton and shove it into their central mouths. However, many corals only get a minority of their energy in this manner. The rest, up to 90% of their energy, comes not from consuming other organisms — a key characteristic of animal life — but from the sun, via photosynthesis.

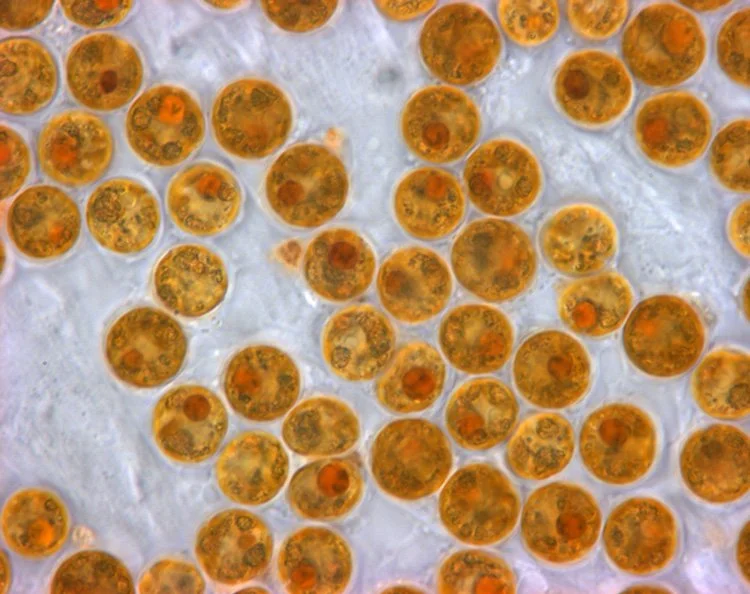

If you look inside the cell of a coral polyp, you’ll find no chloroplasts nor rigid cell walls — these are clearly the cells of an animal. But if you were to examine a coral polyp’s tissue cells, specifically of the inner tissue layer (the endoderm), what you’d discover is microscopic algae living within, and within those single-celled algae is where you’ll find the chloroplasts that carry out photosynthesis.

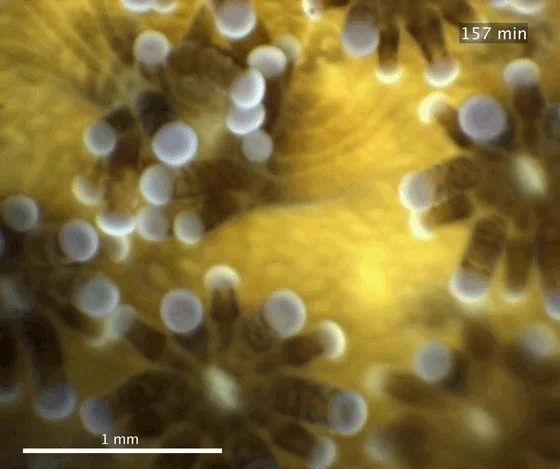

These algae are known as zooxanthellae, or “little yellow animals,” for they are microscopic, they produce the golden-brown pigment often seen in corals, and, while they aren’t animals, they are symbiotic companions to them.

Zooxanthellae provide energy derived from the sun to their corals, and, in return, the corals provide the zooxanthellae with protection — the various bright colours of corals come from a combination of the zooxanthellae’s yellow pigments and those produced by the corals themselves which often serve as “sunscreen,” protecting the corals and their algae from strong UV rays (hence why corals in shallower waters are often more colourful). Corals also provide inorganic nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and carbon dioxide that enable the algae’s photosynthesis. The polyps of a coral, feeding with their tentacles, essentially act like the roots of a plant; drawing nutrients from the surrounding water rather than soil.

“Symbiodinium, colloquially called "zooxanthellae". Corals contain dense populations of round micro-algae commonly referred to as zooxanthellae. A typical coral will have one to several million symbiont cells in an area of tissue the size of a thumbnail.”

But here’s the thing. Corals aren’t the only animals to host zooxanthellae and make use of their photosynthetic abilities. It shouldn’t be too surprising that anemones host them as well, given their similarity to coral polyps. More surprising might be the Cassiopea, or upside-down jellyfish, which orient themselves as per their name to capture more sun for their zooxanthellae, or the giant clams, which open their metre-long shells to reveal golden-brown tissue full of photosynthesising zooxanthellae — without which these clams couldn’t reach such massive sizes.

The difference, however, between the relationships of zooxanthellae and these animals, and zooxanthellae and corals, is one of vitality. To the sea anemone, upside-down jellyfish and giant clam, their symbiotic zooxanthellae is certainly beneficial, but it's not vital. A coral, on the other hand, could not survive, at least not in the long-term, without its algae symbionts. Hence why coral bleaching, when corals expel their zooxanthellae due to stress, eventually kills corals.

All of this — the colonial organisation of polyps, the stationary structure they build, the role of corals in their ecosystems, and their symbiotic relationship with algae — all of this allows corals to fill a niche as close to plants as we’ve yet to see in any animal.

But, when we speak of a coral, what, precisely, is the animal?

Is it the vast branching structure composed of thousands of polyps, or the individual polyp itself? And what about the zooxanthellae inside the coral’s tissues, are they separate organisms, or have they become so integrated as to become part of the corals themselves? At what point can we no longer distinguish an individual from the collective?

In corals we have several levels at which individuality blurs. Let’s begin at the lowest level, the smallest magnification, and work up.

Each single-celled zooxanthellae has its own nucleus, DNA, organelles, and chloroplasts, separate from that of its host polyp. Zooxanthellae are, by most metrics, their own separate organisms. But so too were the ancient bacteria that became chloroplasts in plants (and those that became mitochondria in animals) — still retaining their own separate DNA to this today — yet we’d hardly call them independent organisms. It seems that corals have taken a similar path to their sedentary niche as plants did: incorporating another organism (from a whole different kingdom no less) and using it to photosynthesis. Perhaps they’re just not as far along on that path.

The zooxanthellae occupy a border zone between being individual organisms and a mere part of their corals, just as Aristotle likely would have seen corals themselves as inhabiting the border zone between plant and animal.

As for the coral polyps, each one is, in the most basic sense, a simplified sea anemone: a complete animal with nerves, muscles, tentacles and a mouth. Yet a single polyp cannot survive alone for long, as it’s adapted to sharing the photosynthates and nutrients with its colony mates via connected tissues.

Coral polyps interacting with one another.

What you consider the individual animal, then, seems to depend on the lens you’re looking through. In a biological sense, a coral polyp is the individual animal. In an ecological sense, the whole coral is the animal.

However you define it, it's still at least possible to identify the discrete units, the polyps, that make up a coral — units that, while together form a very plant-like organism, are still animal-like individually.

But what about an organism that can be shredded into a hundred pieces, and not only survive, but survive and grow as one hundred separate, but genetically-identical individuals? Unlike a lone coral polyp, each one of these clones is self-sufficient, and yet none of them have mouths, nor muscles nor any nerves at all. Despite all appearances to the contrary, each of these undifferentiated blobs of cells is an animal.

———

“The sponge,” writes Aristotle, “is in every respect like a vegetable.”

Sponges certainly look pretty “vegetable” from the outside — permanently rooted and unmoving, often asymmetrical, and lacking any visible sensory organs — but what exactly a sponge looks like varies significantly between species. There are sponges that grow like crust on rocks, those with branching coral-like forms, giant smoke-stacks and cauldrons, cups and vases, spheres, fans, and amorphous blobs.

Top left to bottom right: yellow tube sponge, giant barrel sponge, net-sponge, elephant ear sponge, cream honeycomb sponge, and red volcano sponge.

What unifies these many varied forms, as many as 10,000 described species, is structure: organised at the cellular level, and almost non-existent at an anatomical one.

The sponges make up the phylum Porifera, the name meaning “pore-bearing” for the tiny holes that cover a sponge’s surface. These “pores” are actually the hollow insides of narrow and elongated porocyte cells, whose purpose is to connect the outside surface of the sponge to its insides. These hollow cells allow water and food particles to be pumped into the sponges internal cavity, where other types of cells, choanocytes, use their whip-like threads to circulate water in and out of the sponge.

Some of the food particles are then taken by the choanocytes and transferred to a middle “jelly-layer” of the sponges body, where free-swimming cells called amoebocytes digest and transfer nutrients, as well as produce the sponge’s skeleton.⁷ As for respiration, each cell gets oxygen directly from the surrounding water, while a sponge excretes carbon dioxide (as well as other waste products) though the whole surface of its body — hence why sponges tend to smell.

All of this action, this well-organised machinery at the cellular level, enables the sponge’s actual anatomy to be, well, very simple. No circulatory, respiratory, digestive, or even nervous systems — not even the de-centralised nerve nets of anemones and jellyfish. Sponges beg the question: which traits can an animal “give up” and still remain an animal?

A sponge’s ability to pump water through its body demonstrated with green dye.

Despite its vegetable-ness, Aristotle writes that “the sponge possesses sensation; this is a proof of it, that it contracts if it perceives any purpose of tearing it up, and renders the task more difficult. The sponge does the same thing when the winds and waves are violent, that it may not lose its point of attachment.”

While sponges lack anything resembling a nervous system or musculature, they are not insensible nor completely unmoving.

The outer layer of the sponge is covered in epithelial cells (of which porocytes are one type), and sticking out of this skin-layer are sensory cells called cilia that can detect changes in water flow and particulate density, while other cells in the epithelium can detect chemical changes in the surrounding water. So when any factor changes, such as when “the winds and waves are violent” or when there are toxins in the water, a sponge’s epithelial cells narrow their pores, blocking outside access to the sponge’s inner cavity and slowly, cell by cell, contracting the sponge’s entire body. This is perception and reaction as a result of cellular coordination.

It is a sponge’s cellular complexity that allows for its anatomical simplicity. Cells in the human body, each with their different functions, have not infrequently been likened to a colony that works together to keep us alive. Within us, those cells differentiate into a discernible set of organs. Once assembled, they behave less like a living colony than like the components of a machine: gears, bolts, and levers with a purpose in relation to the larger whole.

The cells that make up a sponge seem far more colonial — comparable to a colony of termites, right down to the structure of some sponges resembling termite mounds. Every so often, a group of termites separate from their parent colony. Provided that that group contains the right composition of individuals — including winged, sexually mature forms — they can go on to found a new colony of their own. Similarly, a collection of cells detached from a sponge, if containing the appropriate mix of cell types, may reorganise itself and grow into a separate sponge entirely. In Aristotle’s words, “if the sponge is broken off, it grows again, and is completed from the portion that is left.”

To use a more relevant analogy, a sponge can grow from a piece of its parent just as a plant can grow from a cutting — a slice of stem or root — of its parent. A plant can voluntarily seed offspring using runners, and a sponge can bud off pieces that will grow into new sponges. Both are cases of asexual reproduction, with the resulting offspring being genetically-identical to their parents. But both plants and sponges also reproduce sexually, and, in some ways, quite similarly. As some plants release their pollen on the wind, so too do sponges release their sperm and eggs into the waters, in a synchronised breeding event. When two of these sex cells meet, they form a larval sponge that drifts around on the water currents for a while, like a dandelion seed in the wind, before settling down to grow as a new adult sponge.

Aristotle points out one basal similarity between plants and animals — a feature that “holds good with regard to habits of [all] life.”

“Thus of plants that spring from seed the one function seems to be the reproduction of their own particular species, and the sphere of action with certain animals is similarly limited. The faculty of reproduction, then, is common to all alike.”⁸

The methods of reproduction vary greatly; from clonal runners in plants and clonal buds in sponges and jellies, to seeds carried on the wind or pollen by a bee, to the physical copulation of many active animals. But all organisms produce progeny; a continuation of their species and their own genetic lineage. That is the ultimate meaning of success, evolutionarily speaking. Not survival, nor happiness, but reproduction. Even if an organism is completely insensitive to the world and incapable of any movement, if it can successfully accomplish that goal, it will persist.

From Each According to His Ability, To Each According to His Needs

Animals took the path of active movement and centralized sensing.

Plants took the path of stationary growth and decentralized responsiveness.

This difference arises from both ability and need. Plants are less able to respond to stimuli than animals, so they have less need for quick and detailed senses. But did plants evolve “poorer” senses because they couldn’t move, or did they evolve not to move because of their “poorer” senses?

The ultimate source of the plant kingdom’s immobility is also its ultimate source of energy: the sun.

Plants don’t need to move to get energy; their biological needs are met by the sun above, the soil below, and the air around them. And so they evolved not to move. And because plants evolved not to move, they were unable to quickly respond to changes around them. And so fast, high-resolution senses would be wasted on them — if a blade of grass could see that a cow was coming to chomp it up, what exactly could it do?

Natural selection punishes unnecessary expenditures. And specialised sensory organs, fast-acting muscles, and complex nervous systems are all very costly expenses. But plants do have some needs that aren’t met by sun or soil: namely, reproduction and defense.

Some plants have evolved to reproduce asexually via clonal runners — specialised stems that grow away from the parent plant to produce new, genetically identical offspring. But even in circumstances where plants must “seek out” other plants for the purpose of reproduction, or seek out faraway places to seed and grow, they’ve evolved so that other, more active forces can do those jobs for them.

A gust of wind blows a dandelion’s seeds to more opportune soils, for example, or a dog carries spiny seed burs in its fur. It's not a stretch to say that plants domesticated animals, by attracting them with colourful patterns and lovely smells, and providing them with nectar for their pollination services. Rather than become active themselves, plants have “employed” members of the most active kingdom of life.

While pollination and seed-dispersal are the most prominent services animals provide for plants, they’re not the only ones. Some acacia trees, for instance, are known for hosting colonies of ‘acacia ants’ that protect the tree from browsing herbivores, and, in turn, are given room and board. Aztec ants provide similar protection to their host Cecropia trees, while also repairing any damage done to them — like an army of immune cells that protect their tree from external threats, and stem cells that can heal it.

Perhaps, rather than employment, it's more accurate to call these partnerships — technically mutualistic relationships — where both parties, plant and animal, benefit in some way. One of the most unusual such partnerships is that of the bat and pitcher plant. Hardwicke's woolly bat finds a safe roost and convenient toilet in the fanged pitcher plant, and, in return, the pitcher plant gets the bat’s poop, which satisfies most of the pitcher’s nitrogenous needs.

Whenever movement, speed, or active intervention is required, plants often evolve ways to recruit animals rather than evolve to perform the task themselves.

Most animals, on the other hand, have no choice but to seek out the energy, nutrients, and water that plants can extract from their environments. This is what likely spurred them to evolve increased movement in the first place, which in turn spurred them to evolve more complex senses, which then could have facilitated even more movement, and so on, in a self-reinforcing cycle.

Much of the activity of animals is directed at one another.

Animals must get food before their competitors do. They must defend themselves from other animals trying to make food out of them. They have to find one another to reproduce (for the most part), and perform or do battle in contests for mates.

“There is enmity between such animals as dwell in the same localities or subsist on the food. If the means of subsistence run short, creatures of like kind will fight together. Thus it is said that seals which inhabit one and the same district will fight, male with male, and female with female, until one combatant kills the other, or one is driven away by the other; and their young do even in like manner.” And while animals compete with one another for resources and mates, “all creatures are at enmity with the carnivores, and the carnivores with all the rest, for they all subsist on living creatures.”⁹

“The so-called presbys [goldcrest] or 'old man' is at war with the weasel and the crow, for they prey on her eggs and her brood; and so the turtle-dove with the pyrallis [corn crake or bullfinch], for they live in the same districts and on the same food…and so with kite and the raven, for, owing to his having the advantage from stronger talons and more rapid flight the former can steal whatever the latter is holding, so that it is food also that makes enemies of these.”

The evolution of activity and senses in animals was self-reinforcing; not just that one enabled the increase in the other, but that animals pushed one another to increased sensitivity and activity.

Arms-races between animals resulted in a snow-ball effect, wherein increased movement and senses in some animals, drove the evolution of increased movement and senses in others; all the way from the first single-celled organism to engulf another— microscopic, slow, and likely reliant on the senses of chemical detection and touch — to the cheetah and gazelle — dashing across the savannah at nearly 100 km/h (60 mph), guided by complex and specialised sensory organs like their camera-type eyes.

If your predator can run at 100 km/h, you better be able to match that speed if you want to survive. And if you need to run at 100 km/h, you need more quick and accurate senses than touch, taste, and smell. The same goes for the predator in need of a meal.

But what if your food doesn’t run? And what if your defences aren’t based on speed but structure?

The ecological niches of many “marine objects” are very similar to those of plants.

Just as a plant doesn’t waste resources on specialised sensory organs, neither do razor clams or pens shells. Just as plants don’t need specialised muscles or nervous systems, neither do the sponges. Jellyfish and anemones can make due with a single opening for the ingestion and excretion. Corals survive with their simple methods for capturing food, while, like plants, receiving most of their energy through photosynthesis — where plants partner with animals when they require something to be done at speed, animals partner with plants (or rather photosynthesising algae) to fit into a sedentary niche.

And there are reasons why most plant-like animals are found in our oceans. One is that diffusion works better in water, allowing animals to respire directly through tissues rather than specialised organs like lungs. Another, and perhaps the most important reason, is that the water column is suffused with tiny particles of food, whereas the air, typically, is not.

These animals can get energy without pursuit — by filtering, trapping, or hosting photosynthetic partners — while their defence comes from shells, spicules, toxins, or sheer numbers rather than speed. And even when a particularly plant-like adaptation is required, rather than evolve that trait itself, an animal can borrow from, or partner with an organism from another kingdom, as a coral borrows an algae’s chloroplasts or a flower employs a bee — supplementing one another’s lacks, rather than independently evolving increased complexity.

In fact, some animals even revert in complexity, whether over millions of years or in a single lifetime.

Barnacles descend from active crustaceans with jointed limbs and eyes. Today, they look to be little more than rocky nubs; cemented head-first to surfaces, feeding with modified legs and only retaining the sensory abilities needed to respond to tides and touch.

Sea squirts, meanwhile, begin life as free-swimming larvae, complete with a tail, a primitive eye, and a notochord — the hallmark of their chordate heritage. However, once they find a place to settle, they attach themselves, absorb their own nervous system, and transform into passive filter feeders. This seeming “degeneration,” with loss of movement and senses, would better be called optimisation. The strategy has clearly been successful given that sea squirts have survived for over 500 million years ago.

A volcano barnacle (left) and bluebell sea squirt (right).

© Ria Tan and © Mark Rosenstein / iNaturalist

The arms-race of speed and senses may dominate much of the animal life that we see, or at least pay attention to, but it's not a prerequisite for animal-hood nor the only viable strategy. We humans, pretty complex animals ourselves, have a somewhat biassed view of “lower” animals. But regardless of what we might value or find interesting, life doesn’t evolve towards complexity, but sufficiency.

Hierarchies & Ancestries

In Chapter five of the History of Animals, Aristotle writes that “…after lifeless things in the upward scale comes the plant, and of plants one will differ from another as to its amount of apparent vitality; and, in a word, the whole genus of plants, whilst it is devoid of life as compared with an animal, is endowed with life as compared with other corporeal entities. Indeed, as we just remarked, there is observed in plants a continuous scale of ascent towards the animal.”¹⁰

Image: Great Chain of Being from Retorica Christiana (1579)

This scala naturae, or "ladder of nature," was a linear scale first used by Aristotle to grade animals by their complexity and “completeness,”¹¹ and was later co-opted by the Christian church during the Middle Ages and adapted into a more rigid, divinely ordained hierarchy known as the “Great Chain of Being,” with god and angels at the very top.

This kind of fixed, hierarchical structure is about as far from evolutionary thinking as one can get. And Aristotle, for all his observations of the natural world, was emphatically not an early evolutionist — in fact, he believed species were defined by eternal essences, and could not change.

And yet some of Aristotle's writings do have a hint of evolutionary thinking: “nature proceeds little by little from things lifeless to animal life in such a way that it is impossible to determine the exact line of demarcation, nor on which side thereof an intermediate form should lie.” And because the scala naturae did come about through actual observations, it too contains echoes of the evolutionary process that shaped all of life.

When Aristotle writes that the “change from plants to animals…is gradual,” he doesn’t mean “change” in the temporal sense; of plants turning into animals or vice versa. He’s referring, rather, to the continuous gradient of traits that can be observed in living organisms.

He’s emphasising the blurry divide between plants and animals in a purely descriptive sense; their characteristics blur into one another. What he didn’t realise is that that blurriness is partly a result of continuity, arising from the continuous evolution of life across time. This kind of change truly is gradual, for how can you draw a line that separates an offspring from its parent? And all of life, ultimately, is a long line, or rather many branching lines, of parents and offspring.

Plants did not evolve into animals, but the two kingdoms did share a common ancestor some 1.6 billion years ago. All living things, in fact, share a last universal common ancestor — known as “LUCA,” estimated to have lived over 3.5 billion years ago. You could draw an unbroken line, consisting of direct parents and offsprings, from LUCA to any organism alive today, whether animal, plant, or bacterium.

From LUCA, a line runs to the last common ancestor between plants and animals (as well as fungi and protists), and to the common ancestor of all the animals, whose unbroken branching lineages gave rise to platypuses and pen shells, antelopes and anemones, jumping spiders and jellyfish, kiwi birds and corals, tentacled snakes and sponges.

We can attempt to sort organisms by their physiologies and behaviours — what characteristics they do and do not have — but that is, and has been for over 2,000 years, a difficult task. It is a task made near impossible by the very nature of life itself: by the facts of common descent and adaptation. Animals have been evolving for more than half a billion years, expanding and adapting to fill all the niches they possibly can. Some retain “primitive” traits resembling those of plants, while others evolved complex movement and senses only to later lose them again in accordance with their survival needs.

To find a purely descriptive definition of an “animal” versus, say, a “plant,” is asking for clear boundaries where, by the very nature of life, there are very few. It is for that reason that the change from plants to animals is gradual.

Which traits can an animal lack and still remain an animal? The answer is any and all, for an animal ultimately isn’t defined by its traits.

And so we return to the definition we began with: an animal is any living thing that belongs to the kingdom Animalia. And each animal belongs to this kingdom because they’re all descendants of a single, common ancestor — whether they sprint across the savannah or sit stationary on the sea floor.

¹ What about when that relationship is flipped: when plants eat animals? Carnivorous plants like pitchers and fly-traps also get the majority of their energy by photosynthesis. Their prey, meanwhile, is broken down into essential nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus.

² In some translations of History of Animals Aristotle also includes barnacles among his testacea, even though barnacles — while being sessile and shelled, and resembling shelled molluscs like clams and limpets — are actually crustaceans, more closely related to crabs, lobsters, and shrimp. In testacea he also places sea urchins, which are echinoderms (related to sea stars and cucumbers).

³ Aristotle on the locomotion (or lack thereof) in aquatic animals:

“Again, there are some creatures which are stationary, while others are locomotive; the fixed animals are aquatic, but this is not the case with any of the inhabitants of the land. Many aquatic animals also grow upon each other; this is the case with several genera of shell-fish: the sponge also exhibits some signs of sensation, for they say that it is drawn up with some difficulty, unless the attempt to remove it is made stealthily. Other animals also there are which are alternately fixed together or free, this is the case with a certain kind of acalephe [cnidarians]; some of these become separated during the night, and emigrate. Many animals are separate from each other, but incapable of voluntary movement, as oysters, and the animal called holothuria [sea cucumbers]. Some aquatic animals are swimmers, as fish, and the mollusca, and the malacostraca, as the crabs. Others creep on the bottom, as the crab, for this, though an aquatic animal, naturally creeps.”

⁴ “Cubozoans, or box jellyfish, differ from all other cnidarians by an active fish-like behaviour and an elaborate sensory apparatus. Each of the four sides of the animal carries a conspicuous sensory club (the rhopalium), which has evolved into a bizarre cluster of different eyes.” (Nilsson, et al., 2005)

Each of these clusters contains two image-forming eyes equipped with lenses, similar to those in more complex animals like humans — although a box jellies’ vision is likely quite blurry by comparison. Still, the box jellyfish can use its eyes to avoid obstacles and actively hunt down small fish and shrimp.

⁵ Plants lack dedicated excretory organs. Instead, gases such as carbon dioxide and oxygen diffuse through stomata and lenticels, while other waste compounds are stored in tissues and discarded when leaves or bark are shed.

⁶ The article, Corals and Coral Architecture by Elias Lewis Jr., is definitely worth a read if you’re interested in learning more about corals.

⁷ The amoebocytes, those motile cells that digest and transport nutrients in sponges, also build their skeletons. These skeletons can be soft and flexible; made up of a soft fiber known as spongin. Or they can be hard and prickly; made from needle-like spicules, composed of silica or calcium carbonate. They can also be both, with some sponges having skeletons part-spongin, part-spicule.

⁸ “Now there is one property that animals are found to have in common with plants. For some plants are generated from the seed of plants, whilst other plants are self-generated through the formation of some elemental principle similar to a seed; and of these latter plants some derive their nutriment from the ground, whilst others grow inside other plants, as is mentioned, by the way, in my treatise on Botany. So with animals, some spring from parent animals according to their kind, whilst others grow spontaneously and not from kindred stock; and of these instances of spontaneous generation some come from putrefying earth or vegetable matter, as is the case with a number of insects, while others are spontaneously generated in the inside of animals out of the secretions of their several organs.”

Spontaneous generation, or the idea that life can spring up out of inorganic matter, has been very much in fashion for most of Western history, from the writings of Ancient Greeks and Roman philosophers to medieval texts. Only around the 18th and 19th centuries was the idea thrown out as patently ridiculous; with such figures as Lazzaro Spallanzani (known for his work on echolocation) paving the way for Louis Pasteur (of pasteurisation fame) to definitively disprove the theory using his sterilised swan-necked flasks.

On the topic of reproduction, Aristotle also writes that “in animals where generation goes by heredity, wherever there is duality of sex generation is due to copulation.”

Reproduction in all animals “goes by heredity,” as we now know, and while animal species with two sexes (i.e. most animals) do for the most part need to copulate, there are the rare exceptions which don’t require a partner to have offspring. These self-reproducing animals range from fully asexual species (like the fully-female marbled crayfish and Amazon molly), to partially asexual (like the New Zealand mud snail, with different populations being variously sexual and asexual), to very occasionally asexual (as with some shark species and the California condor, wherein two cases of asexual reproduction were observed).

⁹ Book nine of History of Animals is full of animals at “war.”

“The snake is at war with the weasel and the pig…the merlin is at war with the fox…there is war between the gecko-lizard and the spider…[and] the wolf is at war with the ass, the bull, and the fox.”

¹⁰ This quote comes from D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson’s 1910 translation of Aristotle’s History of Animals. The translation I’ve used for most other quotes is Richard Cresswell’s 1897 translation. On occasion, Aristotle’s text is translated in ways that lead to differences in meaning, and in some cases these translations contradict one another completely.

For example, Cresswell’s translation states that “Of all testacea, the echinus [urchin] appears to have the best sense of smell amongst those that can move.” Meanwhile, Thompson’s translation says that “With regard to testaceans, of the walking or creeping species the urchin appears to have the least developed sense of smell…” — the exact opposite.

¹¹ Aristotle’s “scale of nature” progresses from lifeless things at the bottom, to plants, to plant-like animals (corals, sponges, etc.), to squishy animals (molluscs), to arthropods (insects and crustaceans), to “blooded” egg-layers (amphibians, reptiles, birds), to mammals (with humans, naturally, at the top).

-

ARISTOTLE'S HISTORY OF ANIMALS RICHARD CRESSWELL, M.A.,

ST. JOHN'S COLLEGE, OXFORD. / Project Gutenberg

De Anima (On the soul) Book 2 by Aristotle: Translated by J. A. Smith / Psych Classics

Bay Path University — Plant and animal cells

Molecular Biology of the Cell. 4th edition. — Chloroplast and photosynthesis

The Australian Museum — How spiders see the world

Museum of New Zealand: Te Papa Tongarewa — North Island brown kiwi

Sea Turtle Preservation Society — Sea turtle navigation

The Australian Museum — Upside-down jellyfish

Smithsonian’s National Zoo — Tentacled snake

Function of the appendages in tentacled snakes (Erpeton tentaculatus) By Catania & Gauthier

Born Knowing: Tentacled Snakes Innately Predict Future Prey Behavior by Kenneth C. Catania

Plants have neither synapses nor a nervous system by Robinson & Draguhn

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service — Venus fly trap

Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife — Razor clams

Florida Fish & Wildlife Conservation Commission — Pen shells

The evolution of eyes in the Bivalvia by Brian Morton

Smithsonian Magazine — Scallop eyes

Bailey-Matthews National Shell Museum & Aquarium — Murex snails

Ocean Conservancy — How do jellyfish sting?

Marine Conservation Society — Jellyfish Q&A

Exploring Our Fluid Earth — Phylum Cnidaria

University of California Museum of Paleontology — Intro to Cnidaria

National Geographic — Sea anemones

BBC Discover Wildlife — Box jellyfish

Temporal properties of the lens eyes of the box jellyfish Tripedalia cystophora by O’Connor, et al.

Lake Forest College— Swimming anemone

Missouri Department of Conservation — Hydras

NOAA — What are corals?

Corals of the World — Coral structure and growth

Arizona State University: Ask a Biologist — Corals

Coral Reef Alliance — Coral reefs 101

Coral Reef Alliance — Coral polyps

National Geographic — Corals

The Encyclopaedia Britannica - Vol.22 - 11th ed.

Popular Science Monthly/Volume 1/July 1872/Corals and Coral Architecture

NOAA — Zooxanthellae

Zooxanthellae: The Yellow Symbionts Inside Animals by Noga Stambler

IMARCS — Zooxanthellae

The Australian Museum — Upside down jellyfish

IMARCS — Giant clams

Global Diversity of Sponges (Porifera) by Soest, et al.

Exploring Our Fluid Earth — Phylum Porifera

iNaturalist — Sponge species

University of California Museum of Paleontology — Intro to sponges

Deep Phylogeny and Evolution of Sponges (Phylum Porifera) by Wörheide, et al.

Encyclopædia Britannica — Stolon

Smithsonian: Habitat — Seed dispersal

Scientific American — Seed dispersal

POMAIS — Burr weeds

BBC Discover Wildlife — Pollination

University of Missouri: Extension — Pollination and pollinators

Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute — Aztec ants

Azteca ants repair damage to their Cecropia host plants by Wcislo, et al.

Thai National Parks — Hardwicke’s woolly bat

New Scientist — Hardwicke’s woolly bat

Arms races between and within species by Dawkins & Krebs

Arizona State University: Ask a Biologist — Evolutionarily arms-races/co-evolution

National Geographic — Evolutionary arms-races

Evolution: How a Barnacle Came to Parasitise a Shark by Tommy L.F. Leung

Chesapeake Bay Program — Sea squirt

National Geographic — Evolution of bones and brain

Princeton Insights — Life cycle of sea squirt

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute — Sea squirts

The Scala Naturae and the Continuity of Kinds by Herbert Granger

Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh — Origins of species

The Great Chain of Being: A Study of the History of an Idea by Arthur O. Lovejoy

SPONTANEOUS GENERATIONAND KINDRED NOTIONS IN ANTIQUITY By Dr. Eugene S. McCartney

American Society of Plant Biologists — Plant evolution

Phylogenetic Analysis: Early Evolution of Life by Sarma, et al.