Japanese Giant Salamander

Andrias japonicus

The Japanese giant salamander, one of the largest amphibians in the world, is endemic to Japan’s cold, fast-flowing streams. When disturbed, it oozes a milky, pungent mucus whose scent resembles sanshō (Japanese pepper), giving rise to its Japanese name ōsanshōuo, or “giant pepper fish.”

-

The giant Japanese salamander is an astounding creature — if not the most comely one. It has the ability to breathe through its lumpy skin, regenerate limbs and organs, and secrete a toxic mucus that apparently smells like Japanese peppers. It’s also massive; measuring 1.5 metres (4.9 ft) long and weighing up to 25 kilograms (55 lbs), making it the largest amphibian in Japan and among the largest in the world.

This salamander dwells in the cold, fast-flowing streams and rivers that cascade down mountains and meander through forests. It uses the "warts" (actually sensory organs) concentrated around its head to sense vibrations and electric signals produced by fish in the water around it. When an unwitting fish swims too close, its gargantuan mouth opens — appearing to split its entire head in half — revealing a toothy maw that's almost large enough to envelop a human head. Suction pulls the salamander’s victim into its grasp, where strong jaws clasp the fish and rows of tiny, sharp teeth pierce its slippery body — escape from the salamander's grasp is all but impossible. Like some monster from a folk story, the giant salamander is also known to lurk behind waterfalls. It waits for fish to tumble over the falls and as they splash down, disoriented from the tumble, the waiting monster emerges from behind the rushing water to devour the confused prey. The largest of these salamanders have even been said to hunt larger prey, reportedly killing and eating small deer (although this claim seems pretty far-fetched).

-

This monstrous salamander already sounds like something out of myth, so it should come as no surprise that there exists a yōkai based on this giant amphibian. The hanzaki (はんざき) is essentially a real-life giant salamander made even more horrendous. The kanji form of its name (鯢魚), includes the combination of the character for fish (魚) and child (兒), in reference to the giant yōkai's unsettling wail; said to sound like that of a human baby. Although it is said to live in the wilderness, far from humans, it grows so large that fish no longer satisfy its appetite. And so it wanders into nearby villages, taking cattle and humans in its cavernous mouth, dragging them down to the depths of its watery domain where it consumes them. Like the real giant salamander, the hanzaki is known for its regenerative abilities. The name hanzaki stems from the belief that the salamander's body could be "cut (saku) in half (han) and it would still survive."

From the town of Yabura, in Okayama Prefecture, comes a tale of a man named Hikoshirō, who is said to have slain the hanzaki that terrorised his townsfolk. Sword in hand, he dove into the monster’s watery lair and was swiftly swallowed. He managed, however, to cleave it in half from the inside, instantly ending the life of the 10-metre (33 ft) long hanzaki — this one couldn’t regenerate, apparently. But his story didn’t end happily; not long after killing the yōkai, Hikoshirō and his entire family dropped dead. The townsfolk concluded that the hanzaki’s spirit had come for its revenge, so to appease it they built a small shrine, the Hanzaki Daimyōjin, where they would worship the salamander yōkai to pacify its curse. They still honour the hanzaki in the yearly Hanzaki Festival (on the 8th of August), with food stalls, fireworks, and a giant salamander float that is paraded through the streets. Here you'll also find the Hanzaki Center, dedicated to researching the real-world river monster.

Where Does It Live?

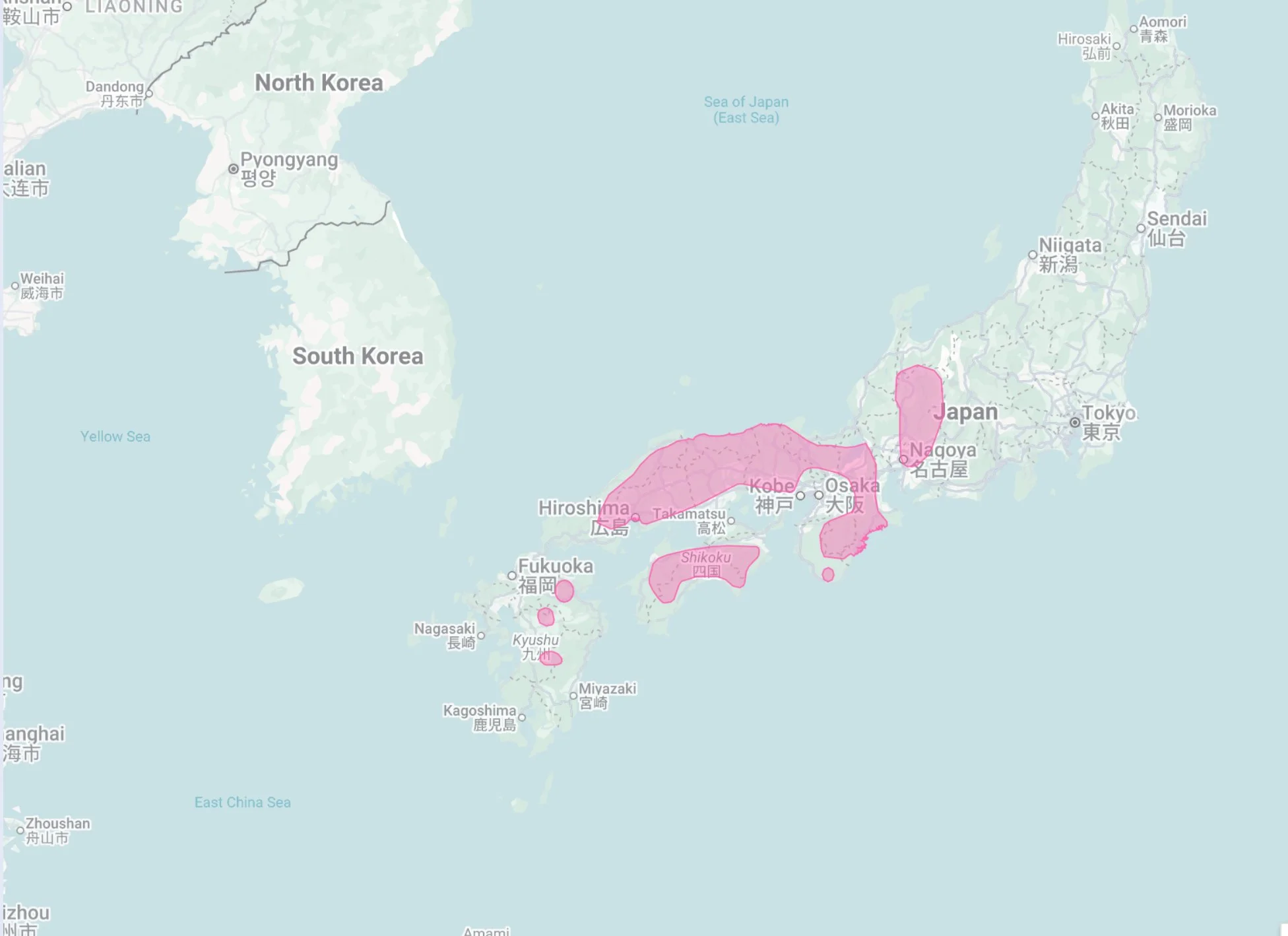

📍Japan; islands of Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu.

⛰️ Cold, fast-flowing, mountain streams.

‘Vulnerable’ as of 06 Apr, 2021.

-

The Japanese giant salamander can reach a length of 1.5 metres (4.9 ft) and a weight of 25 kilograms (55 lbs). It is among the largest of all living amphibians — it was the second largest, before the Chinese giant salamander was recently split into several separate species (the largest of which can grow up to 1.8 metres [5.9 ft] long).

The giant salamander is a nocturnal creature. It sleeps during the day, lying motionless in the water, its drab and lumpy body disappearing against the rounded stones of the river bed. It will rarely leave the water, only doing so when forced to find a new dwelling.

This slimy giant is endemic to the fast-flowing mountain streams of Japan. Enveloped in oxygen-rich water, the salamander’s skin acts as an ideal surface for gas exchange, allowing oxygen to diffuse into the body and carbon dioxide to leave it. The creature's wrinkles and folds increase the available surface area for this amphibious form of respiration. The giant salamander does have lungs — or rather, a single lung — which serves primarily to regulate the salamander’s buoyancy as it walks along the bottoms of streams.

Known as the ōsanshōuo in Japanese, its name translates directly to “giant pepper fish.” The reason is far from appetising, however, as the smell comes from a sticky, white and toxic substance the salamander secretes when stressed.

The "warts" concentrated around its head are actually sensory organs, used to detect vibrations and weak electric fields produced by other creatures in the water around it. These touch and electro-senses, along with a good sense of smell, make up for its tiny, practically useless eyes.

This river monster is a sit-and-wait predator that hunts in the shallows. When an unwitting fish swims too close, the salamander’s gargantuan mouth opens, appearing to split its entire head in half, revealing a toothy maw that's almost large enough to envelop a human head. It uses suction to force its prey into reach — dropping one side of its jaw and creating negative pressure within its mouth — pulling the fish inside, where strong jaws and rows of tiny sharp teeth clasp its slippery body.

The giant salamander is also known to lurk behind waterfalls, waiting for fish to fall from above. As fish tumble down, disoriented, the waiting salamander emerges from behind the rushing water to devour its confused prey. Some of the largest giant salamanders have been said to take much larger prey, even killing and eating small deer, although this claim (Honolulu Zoo) seems pretty far-fetched.

During breeding season, a female giant salamander deposits 400 to 500 eggs into a male's den. Once fertilised, the father — the so-called ‘den master’ — cares for the clutch.

He fans his tail over the mass of eggs, distributing oxygen-rich water to each one.

He periodically agitates them; a technique also used in captivity, known to increase the likelihood of successful hatching, as it stops yolks from adhering where they shouldn't and prevents developmental abnormalities.

He also engages in ‘hygienic filial cannibalism’: to protect his clutch, the father selectively eats any egg showing signs of being dead or infected, preventing pestilence from spreading to the rest of the eggs.

After 12 to 15 weeks of doting care, the eggs finally hatch into larvae. Unlike most amphibian larvae, which are left to fend for themselves, those of the giant salamander remain in the den with their father. They live a comparatively cushy life. They are fed, protected from predators and parasites, and their father continues to care for their hygiene by removing unhealthy or dead larvae (usually by consuming them). All in all, the father is committed to a 7-month plus stint of parental care, from the laying of the eggs in summer/autumn to the dispersal of larvae in the following spring.

Young salamanders grow from 10 centimetre (3.9 in) larvae at the age of one year, to about 35 centimetres (13.8 in) at 4 to 5 years old — the end of the larval period — reaching adulthood at around 15 years and continually growing, to lengths of over a metre (almost 5 feet), throughout an astonishingly long lifespan that can exceed 70 years.

The Japanese giant salamander is considered a Vulnerable species, however, many in the conservation community believe that an Endangered status would be more appropriate. Since 1955, its population is believed to have declined between 30% and 55%, but even that could be an underestimation. Habitat loss is the driving threat; agriculture and flood control barriers built along streams destroy spawning pits and prevent giant salamanders from travelling to meet and mate. One potential solution to the latter threat is the implementation of ramps that would enable salamanders to scramble over these artificial barriers, allowing them to once again move freely along their river systems — a strategy employed by Sustainable Daisen in the Nawa River basin, Daisen

-

Brazil, M. (n.d.). Japan: The Natural History of an Asian Archipelago. Princeton University Press.

Yokai.com — Hanzaki

Explore Okayama — Hanzaki Center

Visit Maniwa — Hanzaki Festival

IGB — Chinese giant salamander

-