White-tipped Sicklebill

Eutoxeres aquila

The white-tipped sicklebill uses its extremely decurved bill to reach inside sharply curved flowers, allowing it to drink nectar other nectarivores cannot reach. It is also a ‘trapliner’ — repeating the same foraging circuits, visiting favourite flowers along its particular route.

What comes to mind when you think of a hummingbird?

Tiny and colourful, wings whirring and heart racing — a woodland fairy, darting through the air in search of its next sugar high. Certainly a long, thin beak, almost needle-like, which it inserts deep into flowers to sip nectar.

There are 360 species of hummingbirds, give or take, all found throughout the New World. They go by fanciful names like sapphire-spangled emerald, amethyst-throated mountain-gem, royal sunangel, and the empress brilliant. Many species are distinguished by their colourful plumage and the shimmering splendor of their gorgets (throat patches). Meanwhile, others flaunt more conspicuous accessories: great big sapphire wings, various styles of head crests, twin streaming tail feathers.

Their bills — indispensable tools of the nectar trade — range from stunted thorns to impressive long swords.

But none are quite as, how to put this nicely… distinctive, as the sicklebills.

Sicklebills

If the bill of your average hummingbird is a needle, the sicklebill has more of a fishhook. Or a sickle, I guess.

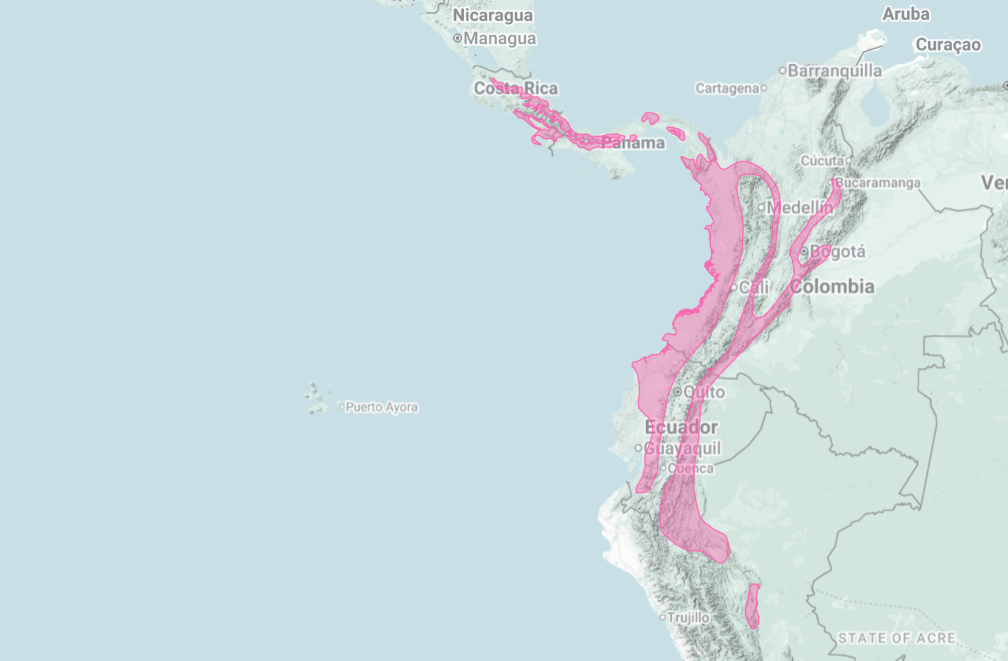

There are just two species: the buff-tailed and the white-tipped. The former ranges from Bolivia up to southern Colombia, the latter from northern Peru north to Costa Rica.

These aren’t your rainbow starfrontlet or red-tailed comets. Sicklebills don’t have long flaming tail feathers (theirs are rather short) nor stunningly colourful plumage (theirs is relatively drab). They’re not as big as the giant hummingbird nor as small as the bee. But they are undeniably unique.

No other species of hummingbirds has a bill quite so contorted — although some, like the long-billed hermit and relatives, do have a downward curve to theirs.¹ The right word for a sicklebill’s bill is bent; it looks like someone took a normal hummingbird and cruelly bent its bill down at a nearly 90° angle. And sicklebills certainly don’t look happy about it either, stuck with permanently sour expressions.

The question, then, is why? What is a bent bill good for?²

Unparalleled Nectar-Eaters

They are nectarivores: nectar eaters, or drinkers. Their eyes have exceptional colour vision, possessing a fourth type of cone cell which allows them to see into spectrums like ultra-violet — revealing hidden (to our eyes) floral patterns. Their tongues are forked, fringed, and able to flick in and out up to 20 times per second, drawing nectar through capillary action and elastic recoil. Their metabolisms are built to run on high-octane, high sugar fuel, their hearts able to beat over 1,200 times a minute, and they require more than their body weight in nectar each day just to stay alive — and their body weight, while seemingly light at around 11 grams (0.4 oz), is more than twice that of the average hummingbird species (you often see sicklebills perching, rather than hovering, while feeding). What little amount of brain they have (little by virtue of their little size in general), they mostly use to navigate the sweet and colourful world of flowers.

Sicklebills are known as ‘trapliners’. Just as a trapper will walk the woods, checking each of his traps in sequence for game, a traplining sicklebill will dart through the montane woodlands, flying fast and low near the ground to visit its favourite flowers along a particular, repeated route. It is those flowers that have shaped its sickle-bill.

In many hummingbird species, the bill is a specialist tool within an already specialised niche.

Thornbills (Ramphomicron and Chalcostigma), for instance, are limited by their short, sharp bills to small flowers with shallow nectar deposits. At the opposite extreme, the sword-billed hummingbird — with its comically overlong bill³ — targets long tubular flowers, such as Passiflora vines in the Andes.

The sicklebills, unsurprisingly, specialise in curved flowers. The white-tipped sicklebill, in particular, shows a distinct preference for Heliconia flowers as well as those of the Centropogon genus, whose narrow tubes often curve downward or sideways and terminate in a small, open mouth where the hummingbird inserts its bill. Odd-looking in isolation, the bird’s bent bill slides into these flowers like a hand into a perfectly-sized glove — or a key that unlocks a treasure-filled chest. And, since few other nectarivores possess the right tools to mine these curved flowers, the sicklebills enjoy a near monopoly on their nectar.⁴ In fact, it has been observed that, in certain habitats, the flower species Heliconia pogonantha is exclusively visited by the white-tipped sicklebill (Stiles 1975), and the Centropogon granulosus exclusively by the buff-tailed (Boehm et al. 2022). Keys in locks indeed.

Paralleled Nectar-Eaters

There are no hummingbirds outside of the Americas.

There are, however, flowers full of nectar. And where there’s a niche, there will be animals to fill it.

Perhaps the most direct Old World parallels to hummingbirds are the sunbirds.

Likewise small and shimmering in iridescent colours, they are nectar-eaters (and insect hunters) equipped with thin, slurping tongues. And just as hummingbird beaks vary, so too do sunbird bills: from the exceptionally long, curved beaks of spiderhunters to the short, unremarkable bill of the pygmy sunbird.

Anyone living outside of the Americas could be forgiven for thinking hummingbirds were more widespread; not because of sunbirds, but because of moths.

Despite not being birds — indeed, belonging to an entirely different phylum — some hawk moth species, notably the hummingbird hawkmoths, bear a striking resemblance to their American avian counterparts: their wings whirr in a speedy blur, allowing them to hover over flowers as they use their proboscises, not beaks, to slurp up flower nectar. And, like the beaks of hummingbirds, hawk moth proboscises can also dictate their specialisation. The Madagascan Xanthopan morganii praedicta, for instance, has a proboscis nearly 30 centimetres (12 inches) long — perfectly suited for feeding from Angraecum sesquipedale, an orchid with an equally long nectar spur.⁵

Also in Madagascar are four species of striking birds known as asities. Two of the species were once known as “false sunbirds” and are now called sunbird-asities, for their shared resemblance. To me, they more resemble the sicklebills; their bills likewise curved in deep grimaces and used for plundering nectar. Even more akin to the sicklebill is the ʻiʻiwi. Belonging to a Hawaiian family known as honeycreepers, which descended from a single species of seed-eating finch, the ʻiʻiwi evolved its greatly curved countenance to drink from the islands’ many flowers.

These are all cases of convergent evolution: when a similar problem (obtaining nectar) is solved in a similar way (specialised probing, mouth parts) by separate lineages (hummingbirds, sunbirds, asities, ʻiʻiwis, and hawk moths).

Maybe the sicklebills aren’t all that odd after all — just another answer to the niche of the nectar-eater. A different bend on a familiar theme. But among the many and varied proboscises, tongues, and bills, few nectar-eaters are quite so unmistakably shaped by their flowers as the sicklebills.

¹ Other hummingbirds with decurved bills are mostly all hermit species: the green, bronzy, white-whiskered, scale-throated, etc. None, however, feature bills nearly as decurved as the sicklebills.

² There are, of course, many other types of birds with bent or curved bills, from ibises to hornbills.

Many bent-bill species, like the sicklebills, use their odd appendages for probing — except they probe for different treasures. The red-billed scythebill uses its down-curved beak to probe crevices and holes for spiders. The ibisbill probe the rocks and gravel of streambeds for aquatic insect larvae. Something has gone awry with the bill of the wrybill, as it curves not up or down but to the right: regardless, it is likewise thought to use it in getting insect larvae from beneath rocks.

³ The sword-billed hummingbird has the largest bill of any hummingbird species. Its bill measures around 10 centimetres (4 inches) long — almost as long as its entire head, body, and tail.

⁴ The white-tipped sicklebill also eats insects, usually stealing them from spiderwebs. Rather than use the tip of its beak, it’ll often open its mouth large — revealing a yellow interior and exacerbating its scowl into a gaping “frown” — to swallow its grubby snack.

⁵ In 1862, Darwin received a package containing a peculiar orchid from Madagascar, noting the "astonishing length" of its flowers. Despite never setting foot on Madagascar, Darwin predicted that there must exist an as-of-yet-unknown species of moth with an equally long proboscis that is responsible for pollinating this flower. Alfred Russel Wallace, the co-discoverer of evolution by natural selection, supported the idea and added that the species is likely to be an African hawk moth. Decades later, in 1903, a hawk moth was discovered on Madagascar with a proboscis that can unfurl to lengths of 28.5 centimetres (11 inches) — it was given the subspecies epithet of praedicta.

Where Does It Live?

⛰️ Humid foothills and montane cloud forests.

📍 Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador; Panama, and Peru.

‘Least Concerned’ as of 29 Jun, 2022.

-

Size // Small

Length // 13 cm (5 in)

Weight // 11 g (0.4 oz)

-

Activity: Diurnal ☀️

Lifestyle: Solitary 👤

Lifespan: N/A

Diet: Omnivore (primarily Nectarivore)

Favorite Food: Flower nectar 🌺

-

Class: Aves

Order: Apodiformes

Family: Trochilidae

Genus: Eutoxeres

Species: E. aquila

-

There are two species of sicklebill hummingbirds (both in the genus Eutoxeres): the white-tipped and the buff-tailed. The former ranges from Costa Rica to Bolivia, while the latter is more restricted to the eastern Andes.

Uniquely among hummingbirds, while sipping nectar, the sicklebills will often cling to flowers rather than hovering — likely related to their “heft,” weighing some 11 grams (0.4 oz), compared to the average hummingbird’s 2.5 to 4.5 grams (0.1–1.5 oz).

Sicklebills are known as ‘trapliners’. Just as a trapper walks the woods, checking each of his traps in sequence for game, a traplining sicklebill darts through woodlands to visit its favourite flowers along a particular, repeated route.

The sicklebills are nectar-eating specialists; specialising, unsurprisingly, in curved flowers. The white-tipped sicklebill shows a distinct preference for Heliconia flowers as well as those of the Centropogon genus, whose narrow tubes often curve downward or sideways and terminate in a small, open mouth where the hummingbird inserts its bill. We’ve also observed that the flower species Centropogon granulosus is exclusively visited by the buff-tailed

The extreme bill–flower match is a classic textbook example of coevolution, but it also makes both bird and plant vulnerable — if either declines, the other may struggle. Thankfully, both sicklebill species are currently of ‘least concern’.

-

Birds of the World — Buff-tailed sicklebill

A Nest of Eutoxeres Aquila Heterures in Western Eestern Ecuador by Gregory O. Vigle — University of South Florida

CATALOGUE OF A COLLECTION OF HUMMING BIRDS FROM ECUADOR AND COLOMBIA by Harry C. Oberholser

LII.—On some additional species of the genus Eutoxeres by J. Gould F.R.S.

IUCN Red List — Buff-tailed sicklebill

iNaturalist — observations map of hummingbirds

iNaturalist — observations map of sphinx moths

Natural History Museum — new moth species predicted by Darwin and Wallace

ScientificLib — Xanthopan morganii, the long-tongued moth

Birds of the World — Sword-billed hummingbird

Birds of the World — Yellow-bellied sunbird-Asity

Birds of the World — ʻIʻiwi

Birds of the World — Red-billed scythebill

Birds of the World — Ibisbill

Birds of the World — Wrybill

-

Cover Photo (© David Le / Macaulay Library)

Text Photo #01 (© Daniel Mérida / Macaulay Library)

Text Photo #02 (© Jeff Hapeman / Macaulay Library)

Text Photo #03 (© Nick Athanas / Macaulay Library)

Text Photo #04 (© Guillermo Saborío Vega / Macaulay Library)

Text Photo #05 (© Juan Carlos Luna Garcia / Macaulay Library)

Text Photo #06 (© Tini & Jacob Wijpkema / Macaulay Library)

Text Photo #07 (© Ayuwat Jearwattanakanok and © Yeray Seminario / Macaulay Library)

Text Photo #08 (© sheau torng lim / Macaulay Library)

Text Photo #09 (My own photo, taken in Barcelona, Spain)

Text Photo #10 (© Dustin Chen / Macaulay Library)

Text Photo #11 (© Phil Chaon / Macaulay Library)

Text Photo #12 (© Jeff Hapeman / Macaulay Library)

Text Photo #13 (© Esculapio / Wikimedia Commons)

Slide Photo #01 (© Josanel Sugasti -photographyandbirdingtourspanama / Macaulay Library)

Slide Photo #02 (© Patrick Palines / Macaulay Library)

Slide Photo #03 (© Ting-Wei (廷維) HUNG (洪) / Macaulay Library)