Pig-nosed Turtle

Carettochelys insculpta

The pig-nosed turtle is the sole surviving species in its family. It lives in the rivers of northern Australia and southern New Guinea, using its pig-like nose to "snorkel" without exposing the rest of its body.

The Turtle Family Tree

There are over 360 living species of turtles belonging to 13-14 different families.

There are large and widespread families like Emydidae, the pond and box turtles, with 50-60 species spread across six different continents. The family Chelidae consists of about 60 species of turtles with necks so long they can't fully retracted them into their shells. There are the tortoises, 40–50 species in the family Testudinidae, which are just a particularly terrestrial subset of turtles, ranging in size from the 130-gram (4.6-oz) speckled tortoise to the 300-kilogram (660 lb) Galápagos tortoise. And there's also the family Trionychidae, made up of some 35 species of carnivorous turtles with soft shells and snorkel-noses.

Then we have the more exclusive turtle families. Podocnemididae has just eight species of river turtles — distributed somewhat unusually: with seven species in South America and one on Madagascar. There’s the iconic sea turtle family, Cheloniidae, with just six species, including the green sea turtle, the figurehead of turtle-kind. The pugnacious snapping turtles, family Chelydridae, have even fewer species, with anywhere from five to only two, depending on who you ask.

Finally, a few turtles have no close living relatives; they are singular species, all alone in their respective families. There's the leatherback sea turtle — the largest of all turtles, weighing up to 900 kilograms (2,000 lbs) — whose distinctly soft shell and massive size set it apart (alone in the family Dermochelyidae) from the other sea turtles. The big-headed turtle, with its disproportionately large and armoured head, is the only member of the family Platysternidae, and the Central American river turtle is alone in the family Dermatemydidae; both species the sole living representatives of lineages that diverged from all other turtles around 75 and 80 million years ago respectively, when dinosaurs still walked the Earth. But there are older relics still.

From the turtle tree of life juts a particularly long and ancient branch, some 140 million years old. This branch once thrived, sprouting countless offshoots and divergences — species in Europe, Asia, Africa and North America. A globe-spanning dynasty. All of the twigs along this branch have since withered and died, leaving behind a barren and linear limb with a single species at its end.

Timeless Turtle

The last living member of a 140 million-year-old lineage. You might expect some primaeval reptilian with spines and a gnashing maw — akin to a snapping turtle or a monstrous mata mata — something dinosaurian, even, since its ancestors set off on their independent evolutionary path deep within the age of those terrible lizards. This turtle is not that.

Of all the testudines, the pig-nosed turtle is among the most goofy-looking. It can grow to be 70 centimetres (2.3 ft) long,¹ the surface of its shell covered in a layer of leathery skin — like that of a softshell turtle — not bony scutes. It has paddle-like flippers and webbed hind feet, similar in shape to a sea turtle's. So far, so normal. But, as its name so directly states, its sniffer has a peculiarly porcine quality. Whereas most turtle "noses" consist of two holes at the fronts of their bony beaks, this turtle has a fleshy snout terminating in two expansive nostrils. The name is apt; this turtle has a pig nose.

Its piggy proboscis aside, the pig-nosed turtle also has a habit of either looking very grumpy, with its closed mouth in a perpetual frown, or exceedingly jolly when it cracks an open-mouthed "smile". It is perhaps the least fierce-looking turtle in the world. But so what if the pig-nosed turtle isn't some bestial relic of a bygone age? Fierceness doesn't always mean success. The reptilian dinosaurs have long since perished, leaving behind an admittedly successful, but much less frightening group of feathered descendants. Meanwhile, the pig-nosed turtle is still here, in a relatively unchanged form, living much as its ancient ancestors did.

A Snout for Snorkelling & Sensing

The pig-nosed turtle is exceptionally adapted to an aquatic lifestyle. It lives in slow-moving rivers, in water up to 7 metres (23 ft) deep, and occasionally appears in lakes and lagoons. If it doesn't have to leave the water, it won't, and that's partly where its pig-nose comes in useful. With its breathing apparatus located at the end of an extended appendage — its nose on a long snout — it can poke it above the surface without exposing any other part of its body. It snorkels. And to supplement its oxygen intake, it can "breathe" underwater through its throat, which is covered in papillae, or little skin bumps, that increase surface area.

In the often-murky rivers where the pig-nosed turtle lives, its snoot serves as more than just a snorkel. When turbid waters cloud its vision, the fleshy appendage, which contains many sensory receptors, becomes this turtle's primary organ for navigating its environment and everything in it — its conspecifics, its predators, and its prey.

Chance & Change

The life of a pig-nosed turtle involves a lot of chance and change.

To even get a chance at life, its egg must survive for anywhere between 64 and 107 days. A mother will try to give her clutch the best chance she can — she'll make a nest chamber for her eggs, in soil with ideal moisture and at higher elevations to avoid (premature) flooding, and in an area with few predators — but, like a sea turtle, she comes on land to lay and then leaves. She won't stay to watch over her nursery, and she can't anticipate everything. That’s why she lays up to two clutches every year, each containing anywhere from 4 to 39 eggs. A few ought to survive.

For most animal species, sex is determined during fertilisation. Not so for a turtle. A turtle's sex is cemented during its incubation period — influenced by the placement of the egg within its chamber and the whims of the environment. Most turtles are subject to temperature-dependent sex determination: the sex of a hatchling depends on the temperature at which it was incubated as an egg. For a pig-nosed turtle egg at a stable 32°C (89.6°F), its chances of becoming male or female are about equal. Lower that by half a degree (or a full degree Fahrenheit) and the hatchling will pop out as a male. Conversely, raise it by the same amount and it will be a female.

Pig-nosed turtles lay during the dry season and, after a long incubation, the eggs hatch into a wet world — if they must, they can delay their emergence for up to 50 days as they wait for the rains that will flood their chambers, reduce oxygen levels, and trigger their hatching. Finally free from its egg, a 57-millimetre (2.2-in) newborn turtle and all of its surviving siblings simultaneously make for the nearby water, a journey no farther than 5 metres (16 ft).

Half a degree can lead to vastly different lives. If the newborn's incubation chamber was slightly chilly, chances are, once he makes it to water for the first time, he'll never have to touch dry land again. But if the chamber was snug and warm, she'll have to crawl onto land every other year, just as her mother did, to dig her own chambers and lay her own eggs. It takes 14–16 years for a male to reach sexual maturity, whereas a female takes 20–22 years. Not much is known about the underwater "love lives" of these turtles, but evidence points to a less-than-romantic union — in one area, over 50% of adult females had injuries on their necks, possibly from males biting or clutching them with the sharp claws on their front flippers during mating attempts. Soon-to-be mothers band together when the time comes to lay their eggs, often milling about in the shallows and making individual trips onto the bank to dig test nests. Then, in a surreal wave of shuffling turtles, they all slowly storm the land, dig their real chambers, and lay their eggs — sometimes laying in clusters instead of individual nests to reduce predation ² — before returning to the water.

Temperature continues to affect the lives of these turtles into adulthood. The dry season, with its cooler waters, is an active time for pig-nosed turtles (especially males), as they scramble to bask in the warmth of hot springs. As water levels fall in some river systems, they’ll push to crowd into the remaining pools of water. The wet season, with its warmth and abundance of water, slows the pace of life considerably.

Throughout its lifetime, a pig-nosed turtle undergoes a shift in its diet. It starts as an egg-hungry toddler who slurps up its own leftover yolk, becomes a meat-eating teen who hunts insect larvae, shrimp, and snails, and finally a flexitarian adult who eats mostly plant matter, such as leaves and roots or fruits and nuts that fall into the water — with groups of turtles often gathering under fruit-laden, overhanging branches — and indulges in the occasional crustacean or mollusk meal. But the turtle, too, has its place within the food chain. Generally, an adult has little worry about being preyed on; it would take an exceptionally strong set of jaws to get at its tasty bits. And, although it does live alongside some of the bitiest animals in the kingdom — crocodiles — they don’t usually find the effort to be worth it.³ An alternative to raw power is dexterity and craftiness, and unfortunately for the pig-nosed turtle, it shares its home with the most cunning predator on Earth.

The Warradjan & the Piku

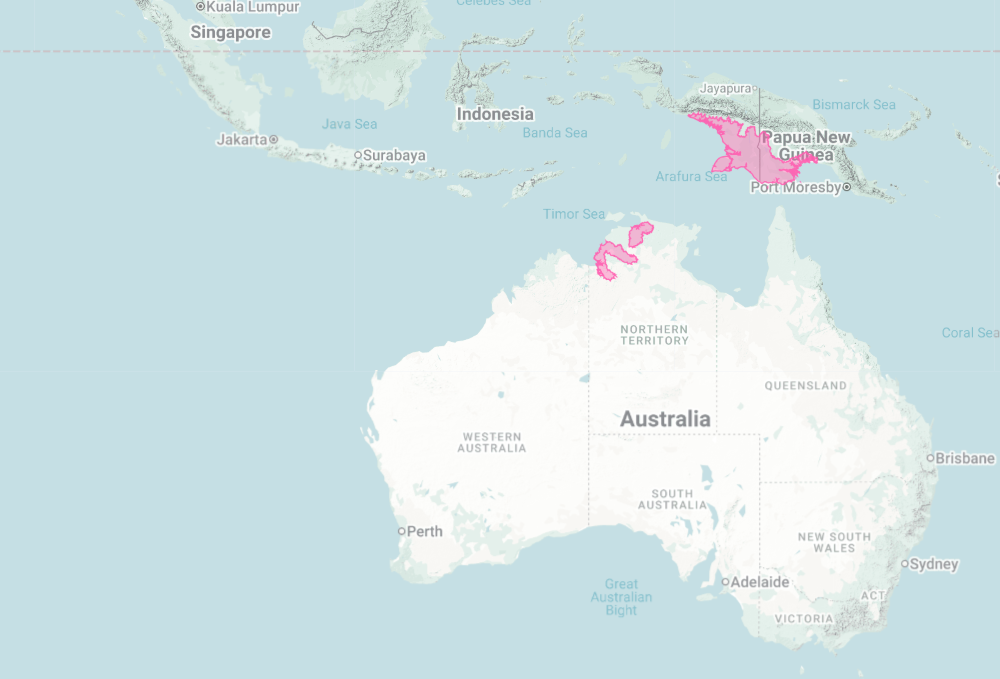

The pig-nosed is a turtle of brackish and freshwater, its population divided by the salty Torres Strait. An alternate name for the species, the Fly River turtle, refers to one of the largest rivers in New Guinea, the island that is home to half of the pig-nosed turtle population, where they’re mostly found in the southern lowlands. The other half, meanwhile, lives in the river systems in the very north of Australia's Northern Territory.⁴ The indigenous peoples on both sides of the strait have a deep-rooted relationship with the pig-nosed turtle; a complicated relationship that involves hunting and eating it.

Across northern Australia, in the Alligator Rivers region and Arnhem Land, you'll find Indigenous rock art depicting the Warradjan — the Kundjeyhmi name for the pig-nosed turtle. Here, this turtle forms part of the local diet — a particularly favoured part, due to its rich taste and size — and it's included in regular meals as well as ceremonies. Along the Alligator River, pig-nosed turtles were traditionally speared from trees or dove upon from the banks, before being placed in a pit with coals and hot rocks, then covered in soil to be roasted whole. Although hunting techniques have changed with the use of baited hand lines, there's no evidence that Indigenous harvesting in Australia has increased to an unsustainable level, and the practice isn't considered a threat to the species today. But there's also little to no evidence that indigenous Australian groups harvest pig-nosed turtle eggs. The story is different over in New Guinea, where some 90% of pig-nosed turtles live.

In Papua New Guinea, where it's locally known as the Piku, the pig-nosed turtle has long been a vital source of protein, and its eggs a prized commodity. However, the eggs collected by locals are rarely eaten by them; they’re instead traded for goods outside of their village or sold to traders for money, who’ll then transport the eggs to Indonesian cities, like Surabaya and Probolinggo in East Java, where they're incubated before being sold on the illegal pet trade. In 2014, it was estimated that some one-and-a-half to two million pig-nosed turtle eggs are collected each year by locals in Papua New Guinea, and the collecting is only becoming more efficient. Foreign traders have worked out a self-perpetuating system wherein they'll trade boats and fuel for turtle eggs — paying the locals in equipment which they can use to more efficiently harvest eggs for them. The egg-collectors, with their new boats, can then reach previously isolated beaches and pilfer every inch of nesting ground. The outcome is a thriving illegal pet trade — more than 80,000 pig-nosed turtles were confiscated by authorities between 2003 and 2013 in Papua New Guinea and Indonesia — and a sharp decline in New Guinea's pig-nosed turtle population.

For a species like the pig-nosed turtle, targeting its eggs is a surefire way to drive it to extinction. The species is slow to mature. Predation on eggs and young is high, so the rate of survival into adulthood is low — every egg counts. And there's no predator as thorough as a human. If we apply the simplest principle of population dynamics to the pig-nosed turtle, we see a death rate that surpasses the birth/hatching rate, and thus a decline in population size. Furthermore, in a situation where the eggs of a long-lived animal are over-harvested, that decline may be hidden from casual observation. We might see a seemingly healthy population of adults in the wild for decades — the estimated lifespan of the pig-nosed turtle is around 80 years, after all — but as individuals grow older, and none of their eggs or offspring survive, we'll suddenly witness the species' population free-fall. An ageing species, doomed to die with no children to take their place. A delayed extinction.

Eggs are the preferred bounty of poachers, but that's not to say the adults are totally safe. Local Papuans typically don't target adult pig-nosed turtles, but when they do, they target the mothers who emerge en masse to lay their eggs. The fully aquatic males, meanwhile, are mostly safe (their biggest danger is ending up as bycatch), resulting in a skewed sex ratio, with some populations comprised of one female for every three males. And, it's needless to say, but without breeding females, there won't be any eggs to steal in the first place.

Indigenous elders from Papua New Guinea reminisce about their youth, they talk about how the beaches were once alive with turtles: "The sand banks moved [and] it was not the sand moving, it was the turtles moving during nesting." It's estimated that, since 1981, human harvesting has caused a 50 per cent decline in the pig-nosed turtle population in Papua New Guinea. Today, the sands are still.

It's currently unknown how many pig-nosed turtles survive on New Guinea — or Australia, for that matter. While the Aussie population may be safe, for the most part, from overexploitation, they remain vulnerable to other threats. A big one is habitat destruction. The turtles are restricted to increasingly smaller ranges, their nesting sites trampled by introduced water buffalo and cattle, and their small population is made smaller — the gene pool more shallow, and thus more susceptible to disease. On top of all that, the changing climate is altering flood patterns, testing the adaptability of an ancient species that doesn't have the genetic variation or time to adapt, and warming up nests so that, in contrast to the situation on New Guinea, more and more turtles are born female — and an all female population is as viable as an all male one.⁵ The future of Australian pig-nosed turtles is far from assured.

Egg by Egg

A species can be both eaten and admired at the same time. Despite the mass exploitation, the pig-nosed turtle is engraved into Papua New Guinea’s 5t coin and the country’s culture. And where there is respect for a species, there are those who want to protect it from harm. An initiative known as the Piku Project was born in the Kikori region of Papua New Guinea with the goals of encouraging “community members to monitor their own levels of harvest and define no-take zones for turtles and eggs”, and this local initiative eventually spawned the Piku Biodiversity Network (PBN). The PBN now promotes piku conservation through education: when young children are taught to love and protect a species, they’re less likely to grow up to exploit it. They might even want to work to save it, and they get to as part of a program called "We Are the Kikori Turtle Rangers”, where local rangers — some of whom have been participating since they were children — monitor turtles, incubate and hatch their eggs, and educate others about the plight of the piku.

Most of the research we have on the pig-nosed turtle has been carried out in Australia by students and researchers from the University of Canberra. Citizen science initiatives like 1 Million Turtles — whose goal is to increase Australia’s freshwater turtle population to one million — demonstrate that more than a few Australians care for their aquatic, shelled neighbours. The pig-nosed turtle is also an important symbol of the Wagiman Rangers, who manage 130,000 hectares of land in northern Australia, where they’ve seen the water levels drop, raising worries for the turtles and sparking interest in future monitoring and research projects.

The efforts seem small in the face of such grave threats, but each step taken is a step away from extinction. Each egg saved is a fresh hope for the species. It’s hard to feel like you, or I, for that matter, can have any kind of impact when we live on the other side of the planet, especially when the survival of a species so critically depends on the actions of those that live alongside it. Funding conservation efforts through donations is a simple contribution — the reality, whether good or bad, is that more money enables more research, more employees, and better facilities. If you’re in a position to, you can call or vote for a change in your country’s policies that impact climate change, whose consequences meddle with the sex ratio of an endangered turtle half a world away. Or you can just tell people about it; share the story of the pig-nosed turtle (and make sure to include photos). Not everyone who learns about this imperilled, snooty turtle will do something about it. Most probably won’t. But a few might, and as more and more people learn about this turtle, the few will become the many. Knowledge opens the door to understanding, understanding leads to empathy, and empathy often grows into love. Who wouldn’t try to save what they love?

Relics

The pig-nosed turtle could have been one species in a family as large as the pond and box turtles, if only its relatives had survived in that great battle for survival. But they didn't. All of the traits unique to its family, all of its line's evolutionary history, are lost when the pig-nosed turtle is. That goes for each of the four lonely turtles — those species that are alone in their families, the last relics of almost-dead lineages. They are either vulnerable (leatherback sea turtle), endangered (pig-nosed turtle), or critically endangered (big-headed and Central American river turtles).

The two pig-nosed turtle populations, in New Guinea and Australia, might pull through. And who knows, maybe in the future their separation will lead them on two distinct pathways, forming two species of pig-nosed turtles — no longer so lonely within their family — creating a new split in a 140-million-year-old line that may, in the far future, become a branch-laden bough once more.

¹ The pig-nosed turtle, at a maximum length of 70 centimetres (2.3 ft) and a weight of up to 30 kilograms (66 lb), is certainly big for a freshwater turtle, but it's not the biggest. The largest freshwater turtle, the Yangtze giant softshell turtle, can grow to over a metre (3.3 ft) long and weigh up to 120 kg (265 lb). It's also almost certainly doomed to extinction, with only two confirmed individuals surviving in the entire world, both male.

² A study conducted at the beaches around the Daly River in Australia's Northern Territory found that two species of monitor most commonly predated pig-nosed turtle nests: Mertens' water monitor, a predator of northern Australia's riparian and aquatic habitats, and the Argus, or yellow-spotted monitor, which is found on both Australia and New Guinea, and uses its digging skills to unearth turtle eggs.

³ An adult pig-nosed turtle, protected by its shell and hefty size, is a tough target for most predators. Youngsters are at a much larger risk of becoming a meal for a monitor or crocodile. The turtle’s body is countershaded, with a dark grey upper side and a cream-coloured underside providing camouflage when viewed from above or below.

⁴ This separation is more intuitive and explainable than that of the Podocnemididae (the family of South American river turtles with one odd, Malagasy member). For much of their history, Australia and New Guinea were connected as one landmass known as Sahul, until rising sea levels split the landmasses apart around 8,000 years ago. As a result, many species occur on both Australia and New Guinea. There’s the short-beaked echidna, agile wallaby, and sugar glider, the southern cassowary and palm cockatoo, the green tree python and white-lipped tree frog, and many more.

⁵ That is, unless the females evolve the ability of parthenogenesis: a form of asexual reproduction where an embryo develops from an unfertilized egg into what is, essentially, a clone of its mother. Although parthenogenesis has never been seen in turtles, some lizards — certain species of whiptails and wall lizards, as well as the mourning gecko — can reproduce in this way.

Where Does It Live?

⛰️ Freshwater and estuarine environments; slow moving rivers, lakes, and lagoons.

📍 Northern Australia and southern New Guinea.

‘Endangered’ as of 28 May, 2017.

-

Size // Medium

Length // 70 cm (2.3 ft)

Weight // Up to 30 kg (66 lb)

-

Activity: Diurnal & Nocturnal ☀️/🌙

Lifestyle: Social (in the wild) 👥

Lifespan: Up to 40 years

Diet: Omnivore

Favorite Food: Varies across lifetime

-

Class: Reptilia

Order: Testudines

Family: Carettochelyidae

Genus: Carettochelys

Species: C. insculpta

-

The pig-nosed turtle is the only species left of a once-prolific family; a 140-million-year-old lineage with species spanning Europe, Asia, Africa and North America.

This turtle hardly looks like a primordial survivor.

Fairly large, at some 70 centimetres (2.3 ft) long, with a shell covered in leathery skin, the pig-nosed turtle — as per its name — has a piggy proboscis.

Much of the time, it either wears an expression of the utmost grumpiness or a goofy, open-mouthed grin. The inside of its throat is lined with tiny bumps (papillae), increasing the surface area. Why? So it can "breathe" (exchange oxygen) through its throat while underwater.

It mostly gets air by using its porcine appendage as a snorkel. Covered in sensory receptors, the turtle's long snout can also feel its way through murky waters.

It lives in slow-moving or still waters (rivers, lakes, and lagoons) with some 10% of its population in northern Australia and around 90% in southern New Guinea.

Mother pig-nosed turtles will storm sandy banks all at once to dig burrows and lay their eggs. The sex of the young is determined by the temperature at which they incubate:

32°C (89.6°F) = chances of male and female about equal

<32°C (<89.6°F) = more likely to be male

>32°C (>89.6°F) = more likely to be female

Unfortunately, the species is greatly threatened by egg-harvesting in New Guinea — its eggs are incubated and then sold on the illegal pet trade.

These are long-lived and slow to mature reptiles: it takes 14–16 years for a male to reach sexual maturity, whereas a female takes 20–22 years.

A pig-nosed turtle starts life as an egg-hungry toddler who slurps up its own leftover yolk, becomes a meat-eating teen who hunts insect larvae, shrimp, and snails, and finally a flexitarian adult who eats mostly plant matter and indulges in the occasional crustacean or mollusc meal.

The species is currently considered 'endangered', with exact population stats unknown. Where once mother turtles crowded river banks, the sands are empty and still.

-

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (Australia)

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (Australia)

Animal Diversity Web – Emydidae

Animal Diversity Web – Chelidae

Animal Diversity Web – Testudinidae

Galapagos Conservation Trust – The Galapagos Giant Tortoise Fact Sheet

Animal Diversity Web – Trionychidae

NOAA Fisheries – Leatherback Turtle

National Geographic – Leatherback Sea Turtle

EDGE of Existence – Big-headed Turtle

EDGE of Existence – Central American River Turtle

EDGE of Existence – Yangtze Giant Softshell Turtle

Mongabay – Death of last female Yangtze softshell turtle signals end for ‘god turtle’

Australian Museum – The Spread of People to Australia

Kakadu Tourism – Warradjan Cultural Centre

Kakadu National Park – Language

Environmental Sex Determination (Developmental Biology. 6th edition.)

Department of Conservation (NZ) – Takahe

EDGE of Existence – Chacoan Peccary

Australian Museum – Coelacanth (Latimeria chalumnae, Smith 1939)

-

Cover (© daniilphotos / iStock)

Text #01 (My own photo, taken in Taipei, Taiwan)

Text #02 (My own photo, taken in NSW, Australia)

Text #03 (My own photo, taken in Saigon Zoo, Vietnam)

Text #04 (My own photo, taken in Japan)

Text #05 (© Marcos Amend / WCS)

Text #06 (© Bo Pardau / The Nature Conservancy)

Text #07 (Turtle Survival Alliance)

Text #08 (© Doug Perrine / Minden Pictures)

Text #09 (© Adam Francis / HongKongSnakeID)

Text #10 (Turtle Survival Alliance)

Text #11 (© daniilphotos and © Paulo Resende / iStock)

Text #13 (© Ramdani / iNaturalist)

Text #14 (© Bayu Nanda / Earth Journalism)

Text #15 (© Alam Mucharam / Earth Journalism)

Text #16 (© Antara-Teresia May)

Slide #01 (© karma lama / Flickr)