Darwin’s Frog

Rhinoderma darwinii

The male Darwin’s frog “swallows” his offspring — nudging the eggs into his vocal sac — where they soon hatch into tadpoles. He carries them for 50 to 70 days, during which they develop entirely within the sac, before spewing out fully formed froglets.

Vocal Sacs

Of all the features of a frog, its vocal sac must be among the most remarkable. Or at least the oddest.

This membrane of skin grows from the floor of the mouth, forming an elastic chamber that inflates like a balloon just as a frog is about to call. The frog pushes air from its lungs, which bounces back and forth between the vocal sac and the mouth, passing over and repeatedly vibrating the vocal folds — producing sound without ever opening its mouth or exhaling. The sac often swells larger than the frog’s own head, and acts as a natural amplifier for these croaks. The purpose of the calls is often romantic, and since males are the courters among frogs, it is only the males who have vocal sacs.¹

That is the primary purpose of the vocal sac: singing sonorous, sexy songs. But in one frog — a small, leaf-shaped species from the temperate forests of Chile and Argentina — the vocal sac has been repurposed for something far stranger.

An Unconventional Cradle

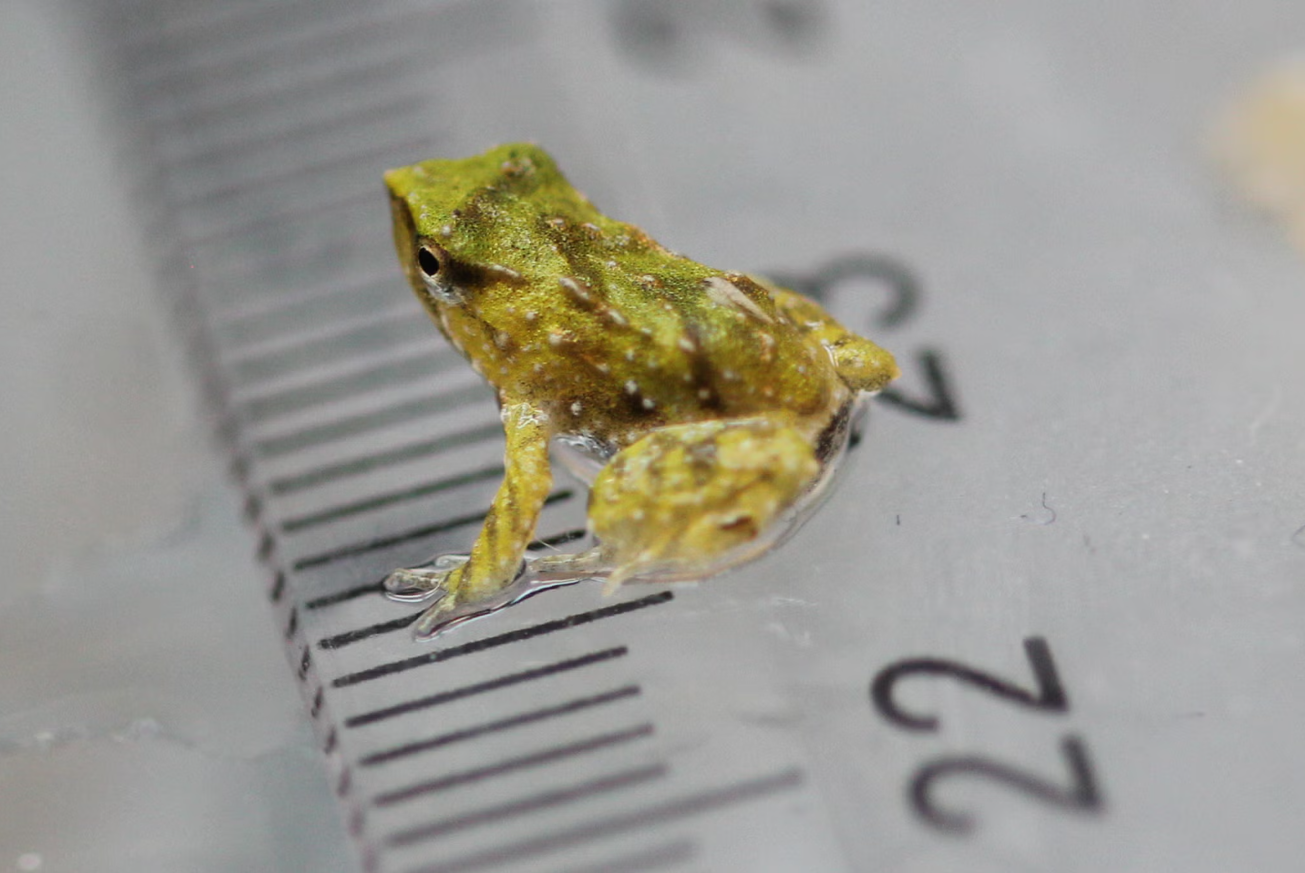

Darwin’s frog is an angular anuran, with a sharp-edged body that culminates in a triangular head and pointy-tipped snout. Green-brown along its back and a darker, spotted underside, it looks not unlike a fallen leaf tucked beneath a log or nestled amidst some moss. And a small leaf, at that, only some 3 centimetres (1 inch) long.

Its call, made during night or day, is more conspicuous than its appearance: a lively whistle ("piiiip, piiiiip, piiiiip, piiiiip") — not unlike a cowboy whistling to his cattle, which may have earned it the local nickname of “cowboy frog”.² But instead of calling to round up its cattle, the frog whistles for the attention of a female. Once attracted and acquainted, the male leads her somewhere more private and sheltered, where they court and mate. Afterwards, the female deposits a clutch of large eggs (anywhere from 3 to 40), and then she leaves.

Most frogs aren’t known for being very attentive parents. They’ll lay their clutch in some place they judge safe — on the edge of a pond, the underside of a leaf, or the inside of a burrow — leaving their offspring’s survival up to luck. But approximately 10–20% of frog species do exhibit parental care. Midwife toads carry their eggs in clusters around their hind legs, and horned tree frogs wear them as backpacks. Marsupial frogs tuck their eggs into pouches of skin on their back. Suriname toads go even further, embedding eggs into their skin, which later hatch out like little pustules bursting from their backs. In these examples, it’s the dedicated (maybe too dedicated, in some cases) mother who cares for and carries her eggs or young.³ Not so for Darwin’s frog.

After the mother has left, the father waits diligently near the fertilized clutch and keeps a watchful eye over it. After 20 or so days of watching and waiting, he notices the larvae begin to wriggle around in their translucent eggs. He approaches his unhatched young…and he swallows them. Okay, he doesn’t really swallow them — not into his stomach, anyway. Instead, he nudges the eggs into his mouth one by one, and draws them into his vocal sac.⁴

Three days later, the eggs hatch into tadpoles. They wriggle and squirm inside their father’s throat pouch, like little aliens, pushing from within his skin, trying to burst out. He continues to carry them as they grow larger and larger — subsisting on yolk from their own eggs and nutritious secretions from their father's sac — for 50 to 70 days. His vocal sac, once an instrument of attraction, is now an overflowing cradle. He’ll serve as a portable daycare until his offspring finally metamorphose into froglets. In the end, fully formed froglets climb out of their father's vocal sac and hop out of his mouth. A less than dignified birth: Darwin’s frog “vomits” up his young.

Rhinoderma darwinii

Darwin’s frog is indeed named after that Darwin. It was discovered by Charles Darwin on his visit to Chile during his voyage on the HMS Beagle and was later named in his honour. Today, this utterly unique frog is considered an ‘endangered’ species.

I say utterly unique, but there is — or was — another Darwin’s frog.

Rhinoderma darwinii, the species we’ve been discussing, is distinguished as the southern Darwin’s frog, while its sister species from central Chile, R. rufum, is called the northern Darwin’s frog. It is the only other vocal-sac-brooding frog that exists — or rather, possibly exists. The other possibility is that it’s extinct. Threatened by habitat loss, climate change, and the chytrid fungus, the northern Darwin’s frog is officially labelled as ‘critically endangered’. It also hasn’t been seen since 1981.

What drove R. rufum to its (possible) extinction is now threatening to do the same to R. darwinii.

The Valdivian temperate rainforests of Chile and Argentina are squeezed into a narrow strip between the coast and the Andes mountains. Along the moist forest floor, Darwin’s frogs crawl rather than swim, eschewing ponds for leaf litter. An estimated 50% of the original rainforest habitat has fallen to deforestation — much of it recently, with 18% of the tree cover present in 2000 now gone. Climate change, meanwhile, threatens the unique combination of mild temperature and high rainfall that makes temperate rainforests such unique biomes, covering just 0.2% of Earth’s land area. And amid these pressures, deadly spores have infected the forest with a fungus known as chytrid.

Since its discovery in the 1990s, the chytrid fungus has contributed to the decline of over 500 amphibian species, with over 90 presumed extinct. This fungus, if it lands on a frog, grows across the surface of its skin, which a frog relies on for gas exchange — for breathing, essentially. The fungus slowly suffocates the frog. In 2023, surveys of Parque Tantauco, once an R. darwinii sanctuary, discovered the arrival of chytrid. Frogs started to die. The death toll of the epidemic came to 1,300 frogs, their pale bodies displaying clear signs of chytridiomycosis, littering the forest floor. The monitored Darwin’s frog populations declined by around 90%.

In response to what can only be described as a crisis, the Zoological Society of London partnered with the NGO Ranita de Darwin in Chile to find, capture, and transport some of the survivors to create a captive population, which then might, one day, be reintroduced back into their natural habitat. Their search through the frog’s mossy forest home yielded 53 healthy, chytrid-free individuals, all of whom survived the 11,250 kilometre (7,000 mile) journey to London. Eleven of those frogs were “pregnant” males. Not long after their arrival, they spewed out 33 new froglets. Or, to be more poetic: from their vocal sacs, these frog fathers sang new hope for their species into being.

¹ Vocal sacs likely evolved from a simple throat pouch, gradually specialised over time as sexual selection — female choice — favoured louder, more resonant males.

² Other explanations for the nickname “cowboy frog” include ridges the frogs possess on their legs that can resemble cowboy boot spurs, or the spotted pattern some Darwin’s frogs have along their bellies (although, for the latter, “cow frog” might be more appropriate).

³ Learn more about these dedicated frog-parents — including the gastric brooding frog (which truly did used to swallow it’s young) — from the horned marsupial frog here!

⁴ As many as 19 embryos have been found within a male's vocal sac (Busse 1970); it is not known what the maximum is.” A full vocal sac doesn’t stop the male from still sometimes calling.

Where Does It Live?

⛰️ Valdivian temperate rainforest.

📍 Mostly Chile and a bit of Argentina.

‘Endangered’ as of 17 Nov, 2017.

-

Size // Tiny

Length // 3 cm (1 in)

Weight // N/A

-

Activity: Diurnal ☀️

Lifestyle: Solitary 👤

Lifespan: 10 - 15 years

Diet: Insectivore

Favorite Food: Herbivorous insects 🦗

-

Class: Amphibia

Order: Anura

Family: Rhinodermatidae

Genus: Rhinoderma

Species: R. darwinii

-

While the majority of frogs display no parental care, Darwin’s frog is one of the exceptions. More unusually, it is the father who cares for the offspring.

The female lays her eggs (anywhere from 3 to 40) and leaves. The male guards them for 20 or so days, until he sees the larvae begin to wriggle around inside. Then he swallows them — or rather, he nudges the eggs into his mouth one by one, and draws them into his vocal sac.

About three days later, the eggs hatch inside the sac. For over two months, they’ll grow and develop in there. What do they eat? Yolk from their own eggs and nutritious secretions from the lining of their father's sac. When development is complete, they are “vomited up” as fully formed froglets.

The froglets are also tiny — as is their father, at only three centimetres (1 inch) long.

The species, Rhinoderma darwinii, is indeed named after that Darwin, who wrote about his encounter with it in the temperate rainforests of Chile.

The only other throat-brooding frog species, R. rufum, is officially classified as ‘critically endangered’, but it hasn’t been seen since 1981.

R. darwinii is currently considered ‘endangered’ — 1,300 frogs were found dead in 2023 after a plague of chytrid fungus hit its habitat. Fifty-three healthy frogs have been caught and relocated to a facility in London with the hope of saving the species. Upon arrival, the males spewed out thirty-three new froglets.

-

The Population Decline and Extinction of Darwin’s Frogs by Claudio Soto-Azat, et al.

Britannica – Vocal sac anatomy and function

BioOne – Evolution of vocal sacs in frogs

FWS – Frog vocalizations explained

Australian Museum – Reasons behind frog calls

Darwin Online – Darwin’s original writings

EDGE of Existence – Northern Darwin’s frog species profile

One Earth – Valdivian temperate forests ecoregion

Patagon Journal – Threats to Chilean forests

Global Forest Watch – Forest monitoring in Chile

GCBO – Chile rainforest conservation project report

-

Cover (© MatiasG / iNaturalist)

Text #01 (Evolution of Vocal Sacs in Anura by Agustín J. Elias-Costa and Julián Faivovich)

Text #02 (© Andrés Valenzuela-Sanchez / UZH)

Text #03 (© Michigan Science Art / ADW)

Text #04 (© martinoli / iNaturalist)

Slide #01 (© Nicole Neira Mena / iNaturalist)

Slide #02 (© London Zoo / ZSL)

Slide #03 (© crisinho / iNaturalist)

Slide #04 (© natchile / iNaturalist)