Why Does Extinction Matter?

We can answer the question from multiple perspectives.

One is the ecological perspective.

Every species plays a role within its ecosystem, so the consequences of one species' extinction reach far beyond that species itself.

In other words, when one species disappears, it's not just that species which is affected. When wolves go locally extinct — as happened in Japan and nearly so in Yellowstone National Park — the deer population they previously kept in check surges, their large numbers causing damage to habitat (via over-browsing) and leaving other species, those reliant on that habitat, vulnerable to extinction.

When sea otters were nearly hunted to extinction along the Pacific coast, their prey — sea urchins — exploded in number and destroyed the towering kelp forests through their unchecked appetites. Without the kelp’s shelter and food, fish, crabs, and countless other species vanished, leaving behind near-lifeless zones known as 'urchin barrens'.

This is what denotes a keystone species: remove it, and the rest of the ecosystem falls to pieces.

An extinction can often cause a domino effect, where one species dies out and all those that rely on it follow suit. When all of the New Zealand moas — a group of flightless birds ranging in size from a turkey to the tallest bird that ever lived — went extinct soon after the arrival of humans, their main predator, the giant Haast’s Eagle (with its up to 3-metre wingspan), followed soon after.

Often, the effects of extinction cross kingdom boundaries, with a loss of plant species leading to a loss of animal species or vice versa.

For instance, many fruit- and seed-eating species obviously rely on the plants they feed on. But, in turn, many plants also rely on animals to spread their seeds. Some are specialised, like the mistletoebird of Australia who eats almost exclusively mistletoe seeds and has a small, weak stomach so that seeds come out intact. Others, like the giant cassowaries, act as dispersers for the large seeds of some 70 species of trees and the smaller seeds of about 80 plant species. And it’s not just birds; squirrels, primates, elephants, ants, and possibly even rattlesnakes all serve as seed dispersers.

An even more intimate example of an animal-plant partnership are figs and their wasps. Each species of fig tree has its own unique species of fig wasp responsible for its pollination (with an estimated 1,300 – 2,600 fig wasp species in existence). On the flip side, the fig wasps use their specific figs as breeding chambers and incubators. Should either party in this arrangement go extinct, the other would die out too.

Speaking of pollination, another perspective to consider is the utilitarian one. What do these species do for us, and what happens when we lose them?

Many services that animals perform for us are related to ecology (a.k.a. ecosystem services). 75% of our major crop species depend on pollinators. Bees most readily come to mind, and — with some 20,000 species of bees — they are arguably the most important pollinator group in the world.

Without honeybees, bumblebees, stingless bees, blueberry bees, squash bees, and many more bee species, we wouldn't have apples or almonds, avocados or pumpkins, cucumbers or zucchinis, cherries, cranberries, or blueberries. But bees are just a portion of the 200,000 or so pollinating animals. Butterflies help pollinate herbs like mint and thyme, beetles pollinate magnolias and water lilies, various flies pollinate carrots, onions and cacao, bats pollinate fruit like guava and durian, while birds pollinate a rainbow of wildflowers throughout the tropics.

To highlight a couple of unconventional examples; if you enjoy a bit of tequila, you can thank lesser long-nosed bats who pollinate the cultivated agave plants from which the drink is made, and if you love the taste of chocolate, you can thank chocolate midges, tiny flies no bigger than pinheads, who can navigate their way through the intricate flowers of cacao plants.

When pollinating species are plentiful and diverse, crop yields increase in both quality and quantity. Even plants that don't require pollination by animals, like strawberries, still produce larger and tastier fruit when pollinators are present. So if you like good food and plenty of it, you can thank pollinators.

As we've seen with wolves, predators help keep prey populations in check. Some of those prey populations are considered pests that eat our crops, spread disease, or are just really annoying.

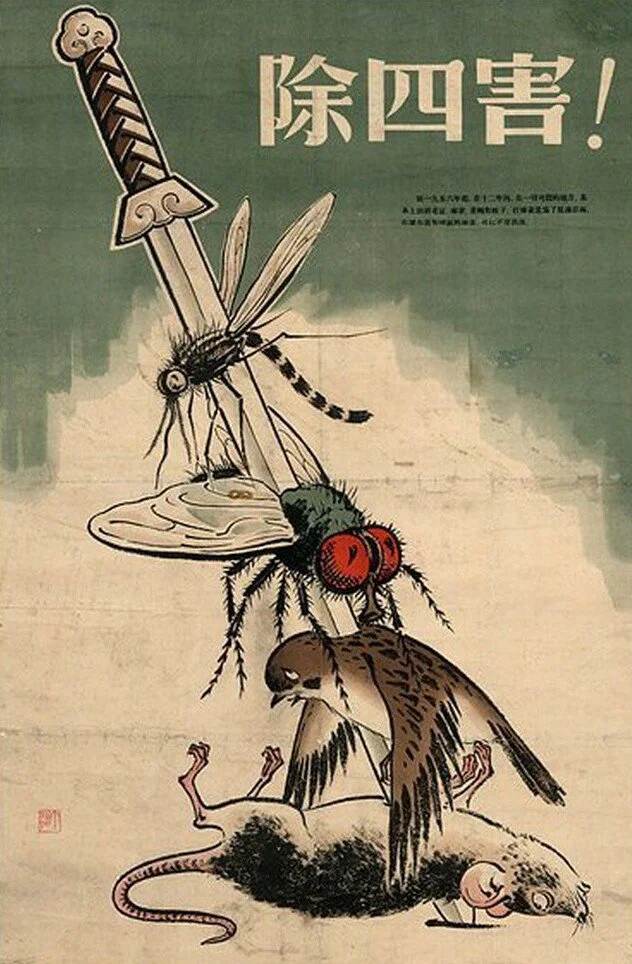

In Maoist China, during the late 1950s, citizens were mobilised to kill sparrows en masse as part of the "Four Pests Campaign" — since sparrows ate grain seeds and fruits, they were thought to reduce crop yields and were thus labelled a pest. After more than a billion sparrows were killed, insect populations (specifically locusts) exploded and devastated crops far worse than the sparrows ever had, contributing to the Great Chinese Famine (1959–1961), which led to tens of millions of human deaths.

In the 1990s, India began using a painkiller known as diclofenac to treat its cattle, "prescribed" very liberally for any kind of pain or inflammation. When a cow passed away, it was simply left out for the vultures — quite literally. As the birds swarmed to clean up the carcasses, they ingested the diclofenac-contaminated meat and swiftly died of kidney failure. The most common species of vultures in the country decreased by 91-98%.

At the same time, the incidence of diseases, including fatal ones like rabies, increased. Vultures acted as dead-ends for harmful diseases, their strong stomachs dissolving the pathogens that festered in carcasses. Without them, those pathogens leached into waterways and spread via infected dogs. Areas that were traditionally home to large numbers of vultures saw a 4.7% increase in the human death rate, contributing to over 100,000 additional deaths per year and an annual economic burden approaching $70 billion. In total, the collapse of India’s vultures may have contributed to the death of more than half a million people between 2000 and 2005 — people who might not have died had vultures still been present.

These are extreme examples, caused by unusual circumstances. But most people could appreciate the swallow or bat that eats hundreds of mosquitoes an hour, sparing us the ear-buzzing and the itching. We can appreciate the owls that stop rodents from overrunning our fields, the ladybugs that devour harmful aphids in our gardens, or even the spiders quietly guarding our homes from insect infestations.

Earthworms aerate our soil, improving its fertility and crop yield. Dung beetles roll, bury, and break down animal waste, helping to recycle nutrients, control parasites, and reduce fly populations in fields. Oysters and mussels filter our water and stabilise our coastlines by acting as natural breakwaters. Every animal has a role in its ecosystem — many of the jobs they do benefit us too.

Animals enrich our lives in more direct ways as well.

We get food from them: meat, milk, and eggs. We get wool from sheep, cashmere from goats, and silk from silkworms. Horses, donkeys, and camels have carried our burdens for millennia. Dogs, our oldest animal companions, have helped us herd livestock, guard homes, track game, and now assist people with disabilities. Pigeons once carried messages across battlefields, and falcons hunted from our arms. More recently, mice and flies have unlocked the secrets of genetics and given us insight into everything from inherited diseases to cancer to brain development.

In many areas — such as clothing, medicine, and food — we're moving away from animal-derived products (and rightly so, as many of these practices involve the horrid exploitation of countless animals). But we couldn't have gotten to where we are without them.

And we don't just commandeer the bodies, products, and abilities of animals; we learn from them, too. The process of natural selection has been tinkering and innovating for billions of years. The natural world was our original teacher, and we continue to learn new things from her to this day.

Biomimicry is the idea of using designs or processes from nature to solve our own human challenges. How do you make a train that travels up to 320 km/h (200 mph) but doesn't emit a sonic boom every time it exits a tunnel? Shape its nose like the narrow and streamlined beak of a kingfisher, a bird known for diving into water with barely a splash.

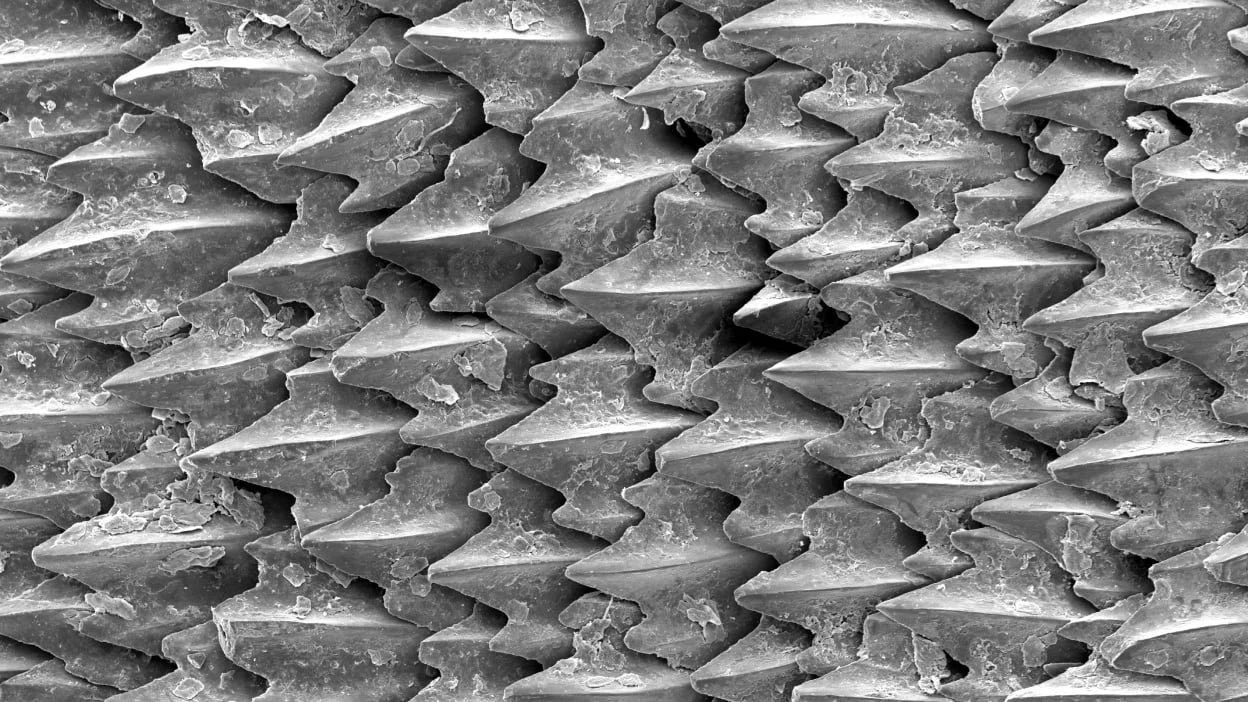

The microscopic hairs on gecko feet, which allow them to stick to almost any surface, have guided scientists in creating advanced adhesive materials. The texture of shark skin has helped create antibacterial surfaces that reduce the spread of microbes in hospitals. The naturally ventilating structure of termite mounds has informed the creation of more energy-efficient buildings with passive cooling and heating systems.

Without electric fish — elephantfishes, knifefishes, and electric eels — we might never have gotten the battery. The Italian physicist Alessandro Volta created the world's first battery in 1800 while seeking to understand and emulate the electrical powers of these fish.

Animals have, and continue to inspire us in ways that go beyond the practical and material.

Animals play a role in every culture across geography and time, interwoven into history and art. From this cultural perspective, the loss of a species could be compared to the burning of a library or the razing of a museum. And more than that. It could be the killing of a culture's very soul.

The American bison once supported every aspect of life for many Plains tribes, and its near-eradication was an act of cultural violence. In the high Himalayas, the elusive snow leopard is a mountain guardian in local Buddhist lore. In Mesoamerica, the quetzal’s dazzling feathers are sacred — its extinction would mean a deity fallen from the sky. While in Hawai‘i, the ‘alalā (Hawaiian crow) was said to guide spirits to their final resting place; it is now extinct in the wild, and the spirits wander without direction.

All around the world, cultures have lost, or are in the process of losing, the creatures that were so closely tied to them and their identities. On the Arabian Peninsula, the Arabian oryx was a creature of poetry and legend; one of the inspirations behind the mythical unicorn. It vanished in the 1970s. In Japan, the red-crowned crane (tancho) embodies hope and long life, its dance inspiring centuries of paintings, textiles, and poems. This symbol of longevity nearly died out in Japan by the early 20th century.

In the Pacific Northwest, the salmon has long been seen as a giver of life — both in a literal sense, providing many river tribes with a vital source of food, and a spiritual one. The salmon is the focus of ceremonies and songs (like the First Salmon ceremony), it is a character in creation myths, a link between different generations, and a symbol of renewal; the renewer of life, running up the rivers every year. By the 1960s, however, the salmon had stopped returning upriver in sufficient numbers. Food source, identity, the very cycle of life put in motion by their Creator — if these salmon died out, more than just a fish would be lost. In the words of the Columbia River Basin tribes; "Without salmon returning to our rivers and streams, we would cease to be Indian people."

It's fortunate that, in many of the above-mentioned cases, the animals were restored to some extent — the oryx was reintroduced to Arabia, the red-crowned crane conserved on Hokkaido, and the salmon replenished through the restoration of rivers and spawning grounds.

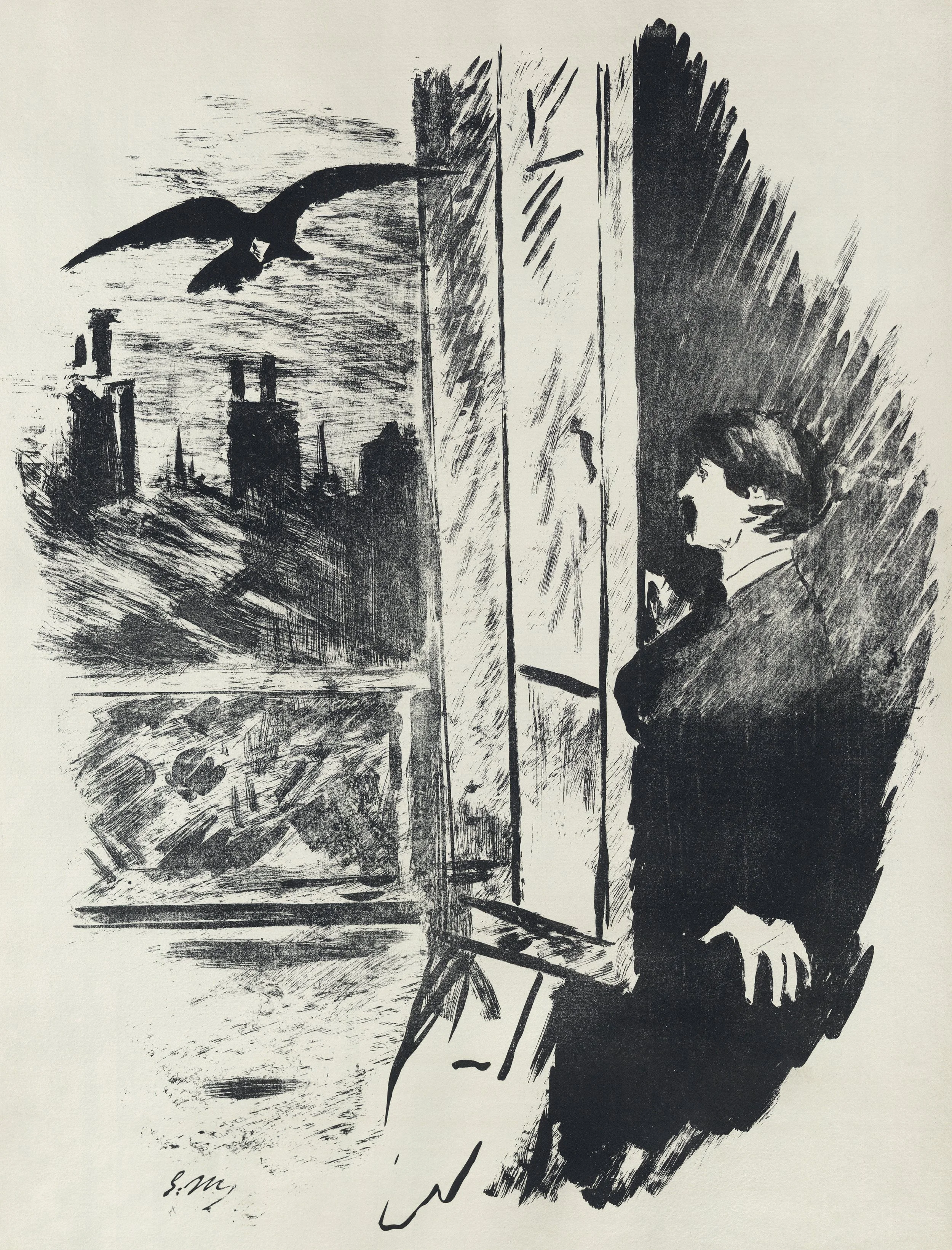

And it's a good thing too, for without inspiration from the natural world it's hard to say what our art would have been like. There would be no ochre aurochsen leaping across cave walls by the flicker of firelight, no jackal-headed gods carved into Egyptian columns, no woodblock prints of cranes and koi, no poetry about ravens or fables about foxes. Ours would be a +much-diminished heritage and a stifled imagination.

It's also hard to deny the inherent beauty in the animals themselves. Viewed through an aesthetic perspective, the natural world displays greater beauty than the totality of our art museums.

The montane forests of the Americas are home to sylphs and sunangels, hermits and woodstars, emeralds and rubies — hummingbirds whizzing around on constant sugar highs. In New Zealand, it is the geckos that resemble precious stones; literally called jewelled geckos, they come in various shades of green and are inlaid with diamonds of white. In Papua New Guinea, there are snails whose shells glow the most vivid emerald green, while those on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola have shells swirled in multi-colour bands like candy canes.

Nature is the ultimate creator and the original source of beauty — if you will permit the personification.

She paints a rainbow with her creatures. A rainbow of red velvet ants, orange clownfish, clouded yellow butterflies, green vine snakes, blue dragon sea slugs, indigo buntings, and violet dropwings. And she chooses a few, and into them pours all her colours: rainbow lorikeets, rainbow scarabs, rainbow boas, and rainbow wrasses. Nature makes from her animals a universe of sea stars and sun bears, moon moths and galaxy frogs. She curates a garden of stick insects, oakleaf butterflies, and orchid mantises.

She makes her animals oh-so-stunning, and then she puts on a show with dancer damselflies that flutter and bounce in flight, birds-of-paradise with mastery of ballet and cabaret, manakins that moonwalk, high-jumping floricans, leaping mudskippers, bateleurs that barrel through the air like untethered acrobats, lyrebirds that can sing sonatas or mimic cell phones, and fireflies that flash and sparkle in sync, turning a dark woodland — ominous, unwelcoming — into fairytale forest with their photic performances.

Just as forests are lit with floating fireflies, every year, thousands of firefly squid rise from the deep sea to spawn, gathering in one Japanese bay and turning the water bright blue with their bioluminescence. A first and final show; the culmination of their short lives

And just offshore there are living statue-gardens composed of sea snails: Triton's trumpets are slow-moving spires, Venus comb murexes the skeletal remains of unidentified aliens, and staghorn murexes are sculptures of burnt tree bark.

In the shallows of our seas, the most magnificent of stages — coral reefs — host dazzling carnivals daily. Harlequin shrimp pose like porcelain statuettes; lionfish flourish deadly fans; psychedelic mandarinfish flit from cover to cover; ribbon eels, neon yellow and blue, perform undulating dances; colourful anemones wave their tentacles back and forth, as if enjoying a concert; shy leafy sea dragons hide from the hubbub by mimicking the foliage; and butterfly fish of all stripes and colours flutter amidst the revelry.

Speaking of butterflies, it's fair to say these winged insects comprise the largest art gallery in the world. Every individual is a tiny, flying canvas. Each of the ~18,000 species is its own little masterpiece, painted and continually refined over millions of years. Peacock butterflies are adorned with faux eyes. Scarlet swallowtails are gothic, monochrome portraits, dripping red. The zebra longwing stretches its canvas horizontally, granting more space for spots and stripes. The glasswing butterfly, meanwhile, has transparent wing membranes; rather than canvas, its wings are windows that frame the beauty of the world through which it floats.

It's not just through appearances that animals inspire awe.

While glasswing butterflies, fireflies, and orchid bees are visually stunning in themselves, they — along with countless other pollinators — are also responsible, not just for many of our crops, but for the blooming of nearly 90% of wild flowering plant species. Most of these plants aren't directly useful to us (as far as we know), so from a purely utilitarian perspective their impact might seem inconsequential. But the world would be a much less colourful place without butterflies, bees, birds, and bats.

On the opposite end of the scale, there is the marvel of mammoth beings.

Elephants, with their wrinkled features and deep social bonds, are the wise elders of the natural world. Giraffes, improbably tall, are moving towers on the savannah; their heads in the heavens, their eyelids heavy as if daydreaming. And then there are the gentle giants in the sea, one of which, the blue whale, is the largest animal to have ever drawn breath — what a wonder, that we get to live in its time.

And what other wonders do we get to live alongside?

These are creatures that may not be beautiful to us in the conventional sense. They may not be all that spectacular in size or outward appearance. But there is something about them — what they do, where they live, how their bodies work — that draws our curious minds to them. These are creatures best seen from the perspective of wonder.

Long, long before we took to the skies, we looked up to the birds who ruled them. Every year, Arctic terns travel from one pole to the other and back again, bar-headed geese journey over the Himalayas, Rüppell's vultures soar alongside commercial aeroplanes at 11,300 metres (37,100 ft), and a wandering albatross racks up enough miles across its long lifespan to journey to the Moon and back more than 10 times.

The skies ripple with massive murmurations: roiling clouds of starlings in their tens of thousands, flowing and contorting into varied three-dimensional shapes as if sharing one mind. The rainforest floor, meanwhile, is alive with billions of ants: army ants waging wars, carpenter ants raising domestic aphids for honeydew, and leafcutters cultivating gardens of fungus. Their cousins on the plains build great termitariums from mud and dung: fields of flat "gravestones" all aligned on a north-south axis and monumental cathedrals up to 8 meters (26 feet) tall, looking like giant melting candles running with wax.

The forests of the world are home to lime-green glass frogs, whose translucent bellies reveal their coiled intestines and beating hearts, and "flying" frogs with parachute-like hands that let they glide from tree to tree.

There are orange-black birds with toxic feathers, and hefty "unicorns" called saolas, which were unknown to the world until the late 20th century. The chicks of phoenix-like hoatzin birds climb through the canopies using their claws, like arboreal raptors, while mata mata turtles with long, craggly necks lie still in forest streams and vacuum up unsuspecting fish into their monstrously grinning mouths.

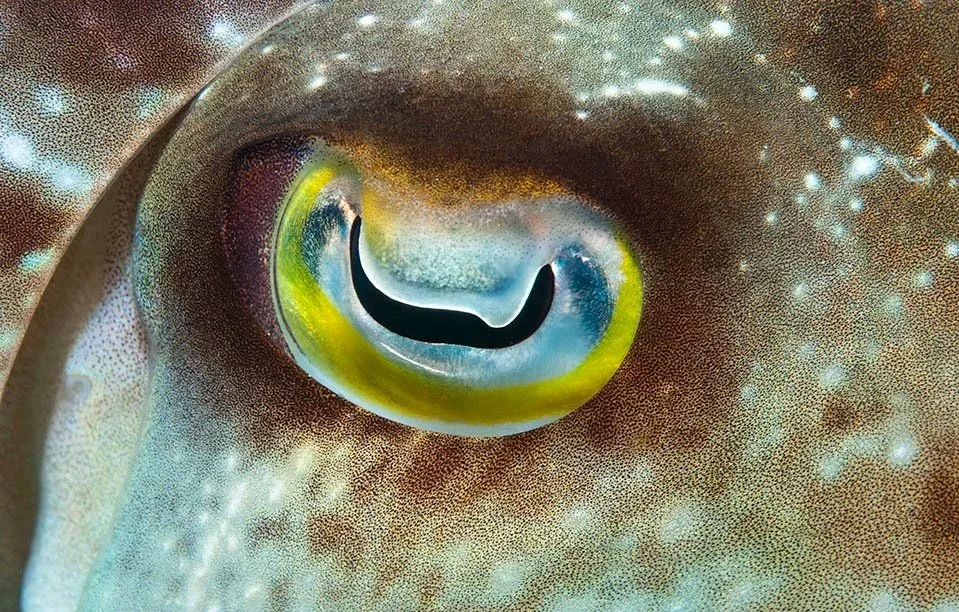

In our lakes are ageless salamanders that can perfectly regrow limbs and organs, even parts of their brains. In our oceans are "aliens" with eight pulsating arms, each one filled with neurons that amount to independent mini-brains. Some of these octopodes create armour from discarded coconut shells, others carry enough toxins to kill up to 26 humans, and others still are master mimics, able to emulate over fifteen species as different as lionfish and sea snakes.

These are creatures that, had you read about them in some old bestiary, you'd be justified in assuming they were made up. But they all live in our world today — at least for now.

Could we ever conceive of what life, what the experience of living, is like for beings so different from us?

In 1974, the philosopher Thomas Nagel published a famous paper called What Is It Like to Be a Bat? In it, he explored the subjectivity of the conscious experience: the idea that each of us sees the world from our own perspective, and we cannot truly know the perspective of another. His choice of titular animal is apt. If it's impossible to know the inner life of another human being, what about other species that experience the world with senses we don't even have?

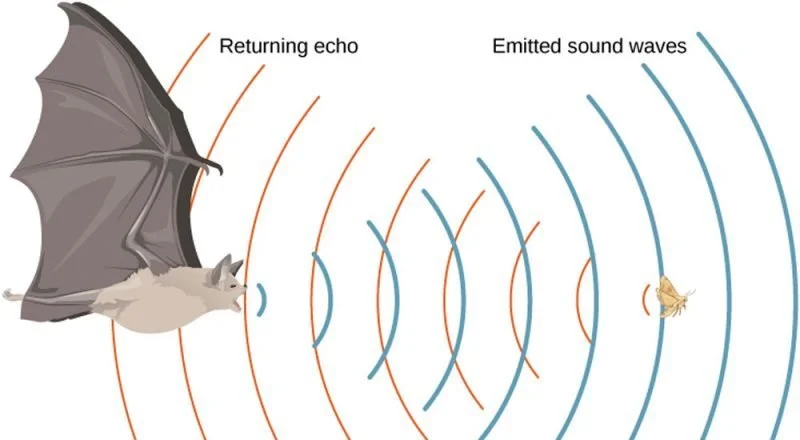

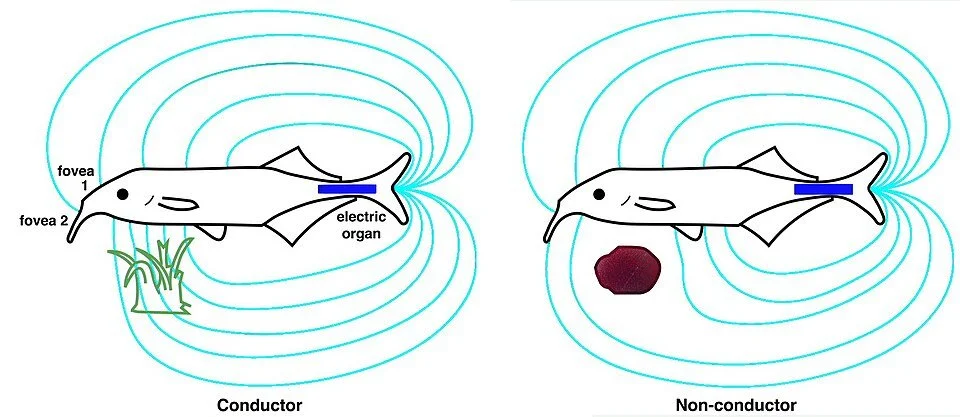

Bats can navigate through pitch darkness using their own echoes to sense obstacles and prey. Pigeons can sense the planet's magnetic field in ways we've yet to understand, enabling them to navigate home from places far and unknown. Knife- and elephantfishes produce weak electric fields that encircle them in three-dimensional figure eights — fields that bend or bunch as they're repelled or conducted by objects in the fishes' surroundings — allowing them to sense anything nearby, like an extended and amplified sense of touch, whether or not it's living.

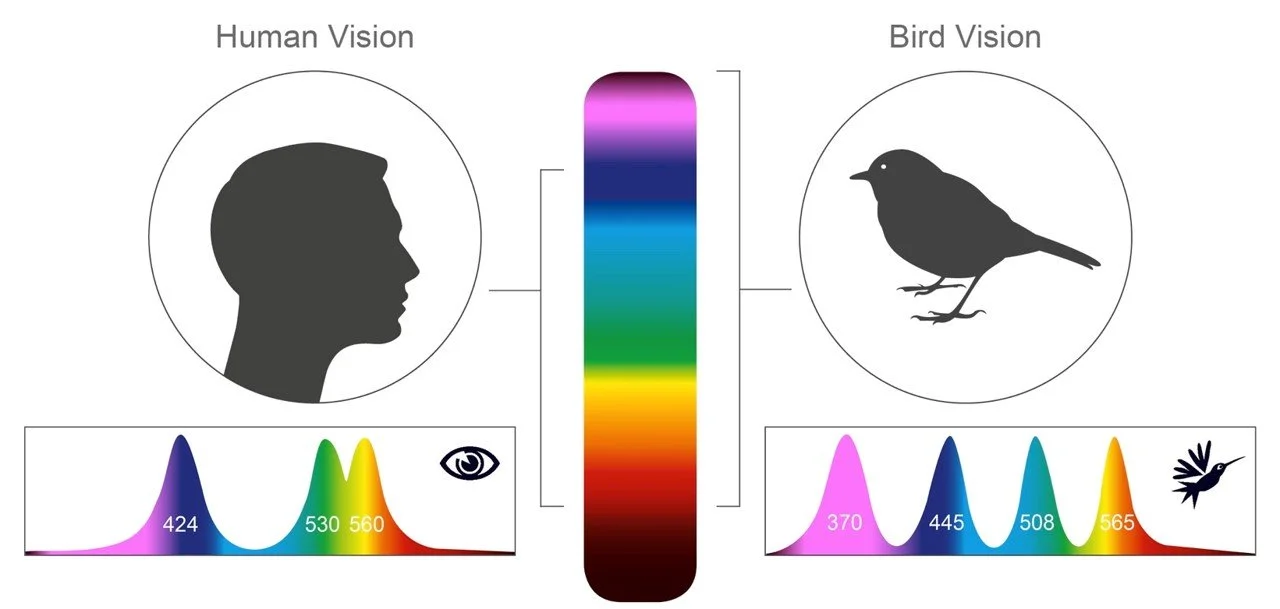

Other animals have the same senses as we do, but on different levels. For example, while humans have three types of cones in our eyes — each sensitive to different wavelengths of light — hummingbirds have four cones, allowing them to see a range of colours our eyes simply can't.

We describe these foreign senses in terms that reference those we do have, but we can't truly experience them as do bats, pigeons, and knifefishes. We're left imagining the colours we cannot see or really even comprehend — what might a field of flowers look like to a hummingbird's eyes? We're made to ponder perspectives beyond our own, and wonder at all the ways of being.

There's a way in which the wonder of the natural world sometimes turns to sadness. For me, personally, it often happens at some point during a visit to a natural history museum. For a while, I read the plaques and stare at the fossils on display. The trilobites from the Permian (252 million years ago), pterosaurs from the end Cretaceous (66 mya), a megalodon jaw from the Pliocene (~3 mya), giant armadillos as big as cars alive during the last ice age (~12,000 years ago), and the thylacine, or Tasmanian “tiger,” extinct in the early 20th century.

And as I fantasise these creatures to life in my head, the realisation dawns that I'll never actually get to see them. For all the recent talk of de-extinction, I know I'll never see a great auk (the "penguin of the north") on a spray-lashed sea stack, a giant ground sloth dragging its claws through South American scrub, or a half-ton elephant bird thundering across Madagascar’s spiny woodlands — not like I can see an elephant striding across the savannah or a blue whale breaching the ocean's surface.

Some day in the future, will people only meet the saola under the artificial lights of a museum, come face to kindred-face with orangutans only behind glass display cases, and only witness the elephant through its skeleton, standing beside those of mammoths? Will they fantasise about seeing a real elephant, an orangutan, a saola — and know they never will, not really?

Perhaps, part of what draws us to the creatures of the past is their mystery. The unknown has always been a source of both fear and wonder.

Myths of hidden continents full of strange beasts and peoples persisted long after the maps were filled in. We've sailed all the oceans, discovered all the continents, traced all the coastlines, penetrated the deepest jungles, climbed the highest peaks, and stood at both the poles. We've found our dragons on Komodo and our unicorns in the Annamites. Now we wonder at the vast unknown that is space beyond. Meanwhile, an uncharted galaxy still exists here, on our own planet.

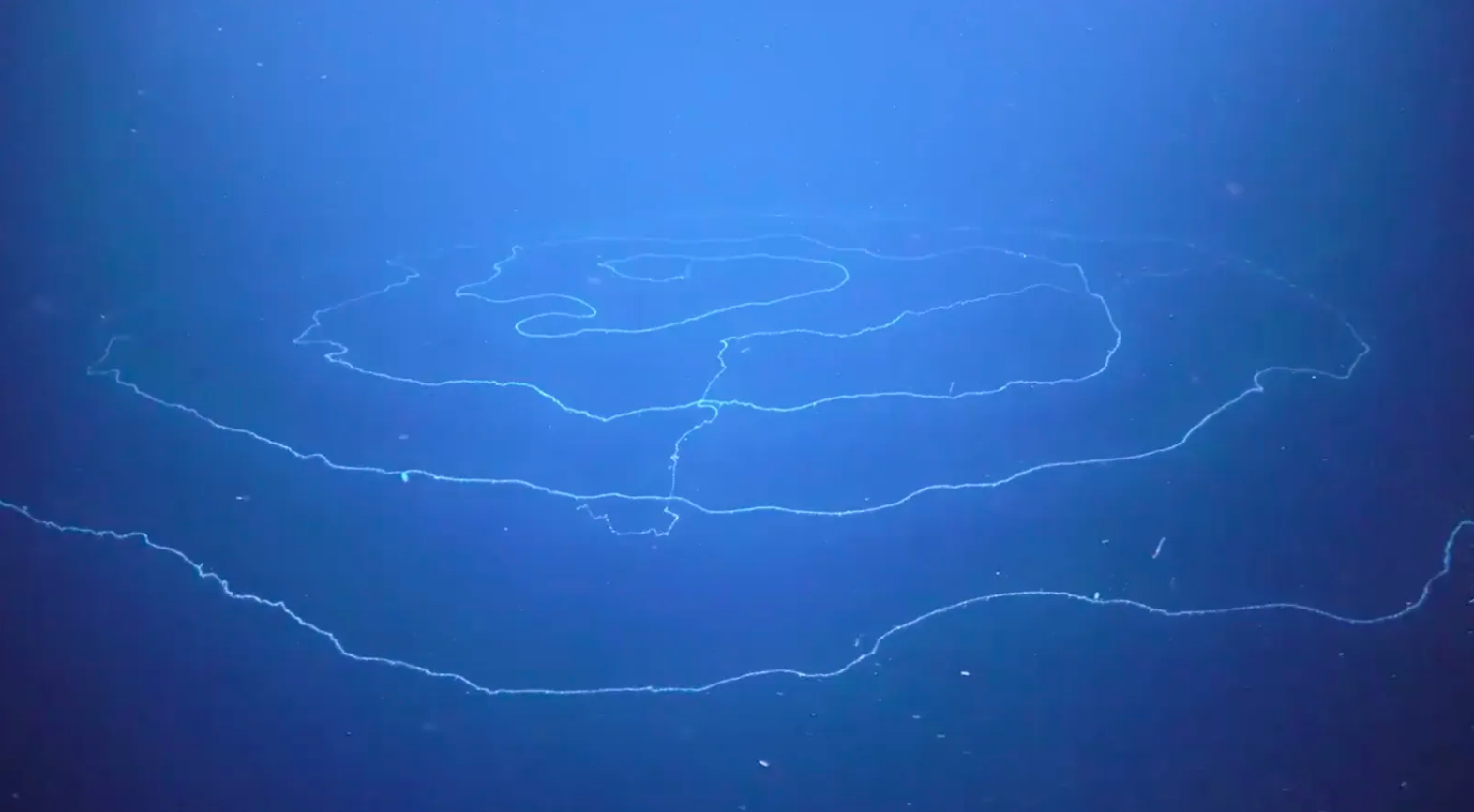

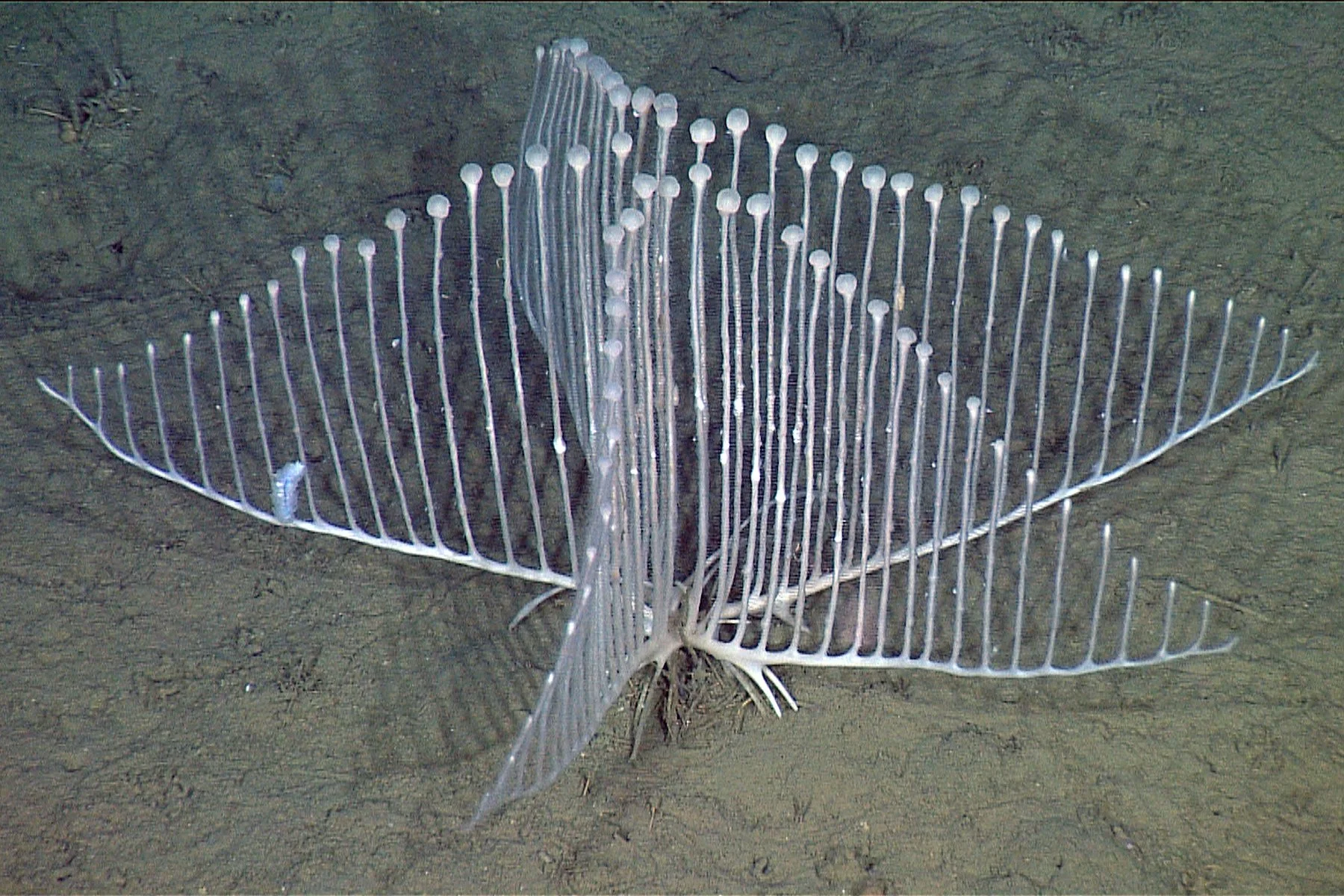

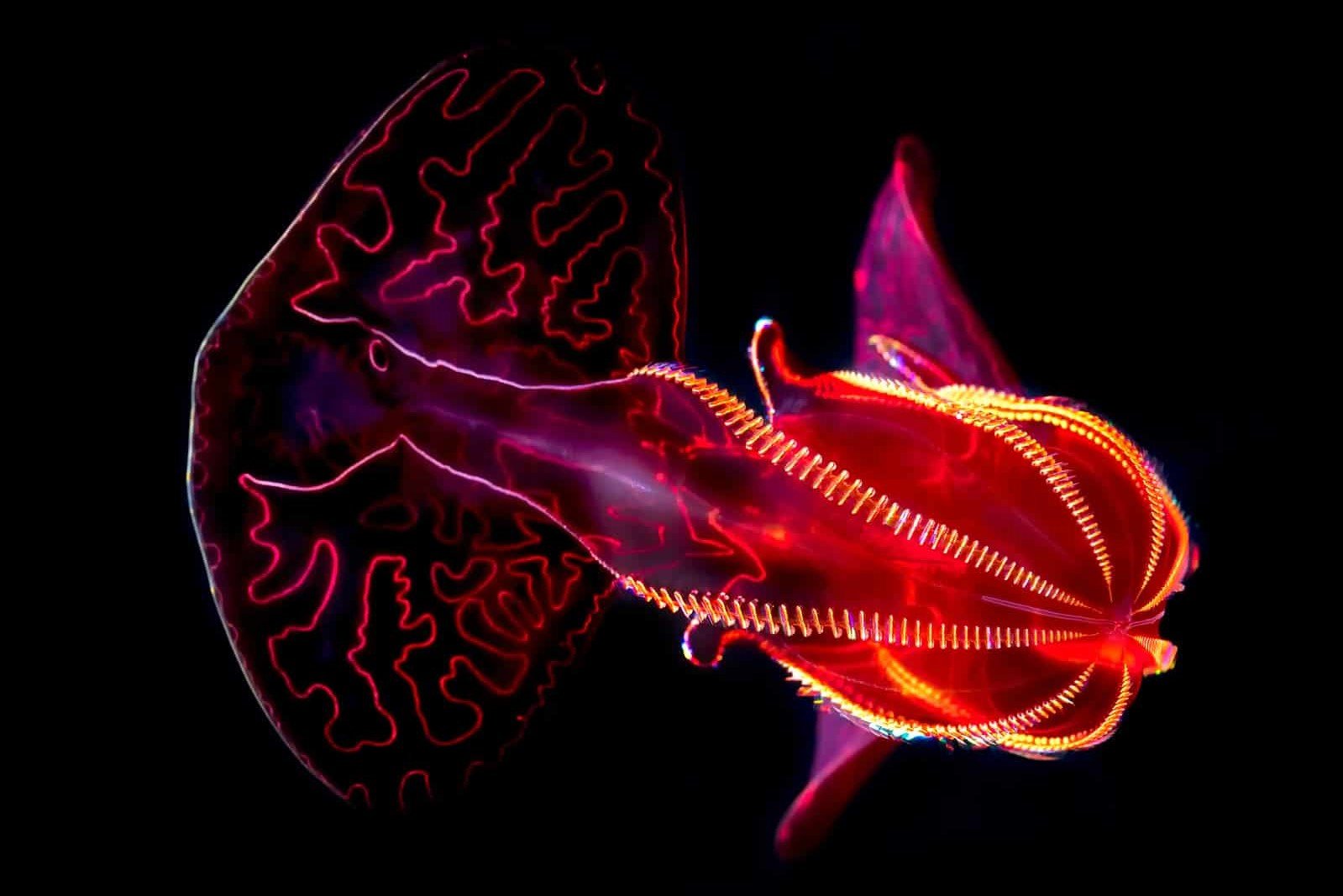

It is a dark space, lacking the light of any sun. It is wet and unimaginably cold, and the weight from above is unbearably heavy. But in this vast and lightless void, millions of blue lights wink on and off; each a twinkling star in this galaxy, each a living creature in the deep abyss. Here there be sea-dragons with skin of the blackest black, pale-pink sea pigs that trundle along the deep-sea floor on tentacle legs, chains of colonial zooids reaching lengths of 40 metres (130 ft), bristly Pompeii worms that lounge by the sides of black smokers — hydrothermal vents that boil the surrounding water — only surviving the heat thanks to fleece-like coats of bacteria. There are sponges that look like harps, comb-jellies that pulse blood-red, spiny porcupine crabs, vampire squids, and sea angels. And that's just a tiny portion of what we've found in the 5% of the oceans we've explored.¹ Can we conquer our fear of the deep and dark, to wonder at the rest of its contents? Can we do so before even these most alien of creatures start to vanish forever?

When we see something peculiar, say an odd critter in the deep sea, we follow and observe in hopes of learning more about it. If we continue to the deepest depths of curiosity — where every fact and detail calls us to investigate further, more systematically — we begin to see from a scientific perspective. Viewed from this perspective, animals have the potential to answer some of life's greatest questions.

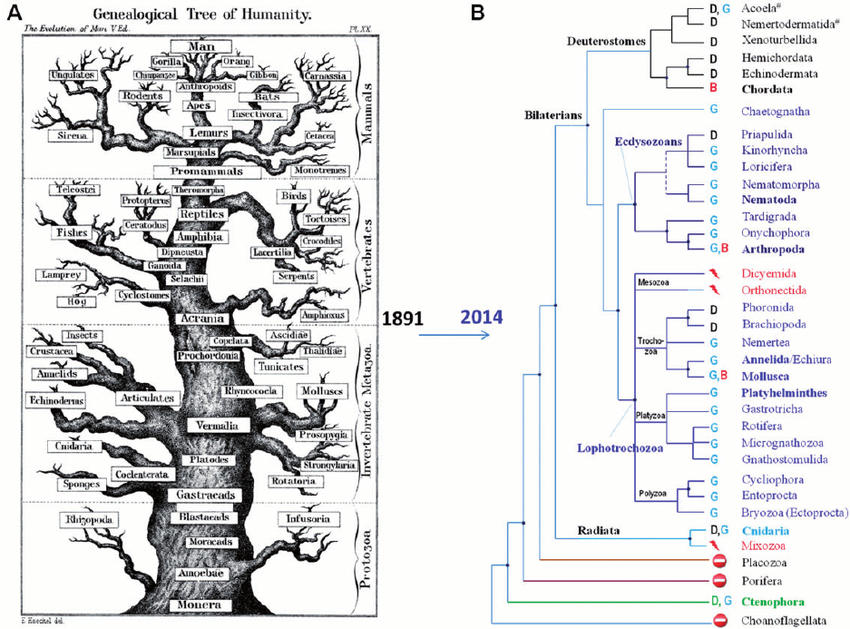

We can view the history of life through fossils we find in the ground. However, given that the vast majority of organisms were never fossilised, that view is through a very narrow keyhole.² In lieu of an extensive fossil record, the study of modern animals offers a window into life in the past and how it came to be what it is today.

Sponges, those simple creatures, may hold clues to the origins of multicellular life. Lancelets, simple fish-like invertebrates with flexible rods (notochords) running down the length of their bodies, help us understand how proper backbones evolved in vertebrates.³ Lungfish may reveal how our distant ancestors first crawled onto land. To find which adaptations made life on land possible, we can look to salamanders with their four-limbed gaits. We can look to reptiles, to their thick scales and calcified eggs, to see a permanent move away from water.⁴

The questions are endless, and modern species, at least in part, hold many of the answers. How did eyes come about? We have over 40 living lineages that evolved them independently, which we can study. What about flight? We can look to countless gliding species, from flying squirrels to sugar gliders, to flying lizards, snakes, and parachuting frogs. And intelligence? We can analyse how distant lineages — from primates to crows to octopuses — differ and converge in their abilities to innovate and problem solve.

All of this insight into the history of life, which we can extrapolate from creatures living in our time, is made possible by one revolutionary idea from the 19th century.

"Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution."

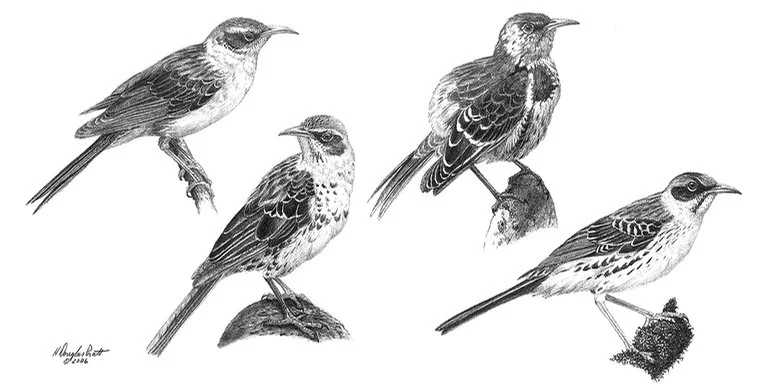

The idea of evolution by natural selection is seemingly so simple on the surface, but it took until 1858 to fully come together and be announced to the world. Charles Darwin was inspired towards his theory — the explanation for the diversity of all life on Earth — by the living species he saw on the Galápagos Islands. The spark was the archipelago's mockingbirds, more so than the famous finches (who often get the credit). Four species of small songbirds (along with some giant tortoise subspecies) from a few distant islands became the catalyst for perhaps the greatest breakthrough in all of biology. What if we'd lost the mockingbirds of the Galápagos before Darwin could come about and be inspired?

Then came the next big biological breakthrough.

Ever since the discovery of the double helix — the winding staircase of DNA that carries the instructions for life — many geneticists have come to see every organism as a kind of book, each a record of a unique evolutionary journey written over millions of years. If only we could read and understand it all, this great library distributed across all living beings, what new secrets could be revealed about the history of life?

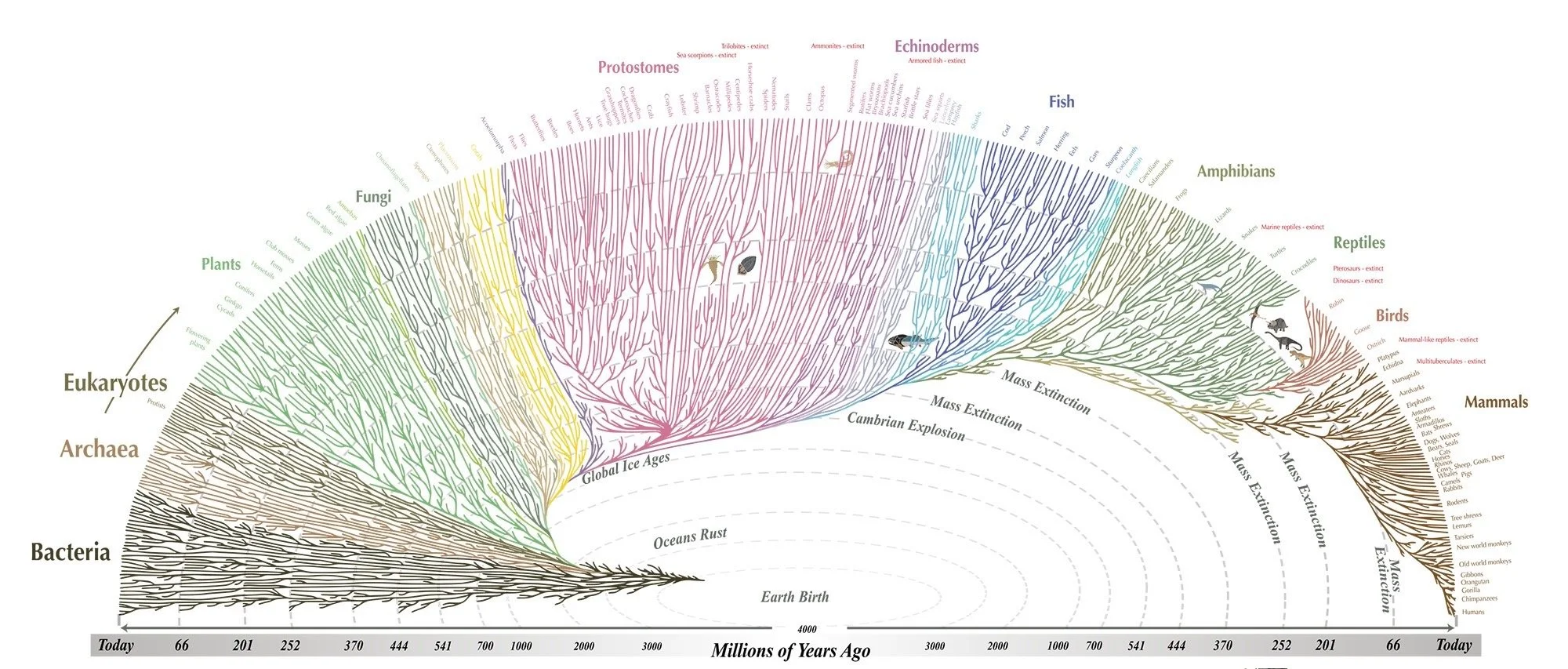

From the parts we've transcribed already, we can map relationships between species with increased accuracy — our evidence is expanded beyond bones in the ground to base pairs of DNA. Whales, it turns out, are closest to hippos. Birds are living dinosaurs. Mushrooms are more closely related to animals than to plants. Some creatures we thought were one species turn out to be many; others, despite looking vastly different, are genetically near-identical.⁵ And we've discovered that all of us, all living organisms on Earth — from humans to chimpanzees, to sea cucumbers, bacteria and trees — are related, sharing a single common ancestor some 4 billion years in the past.

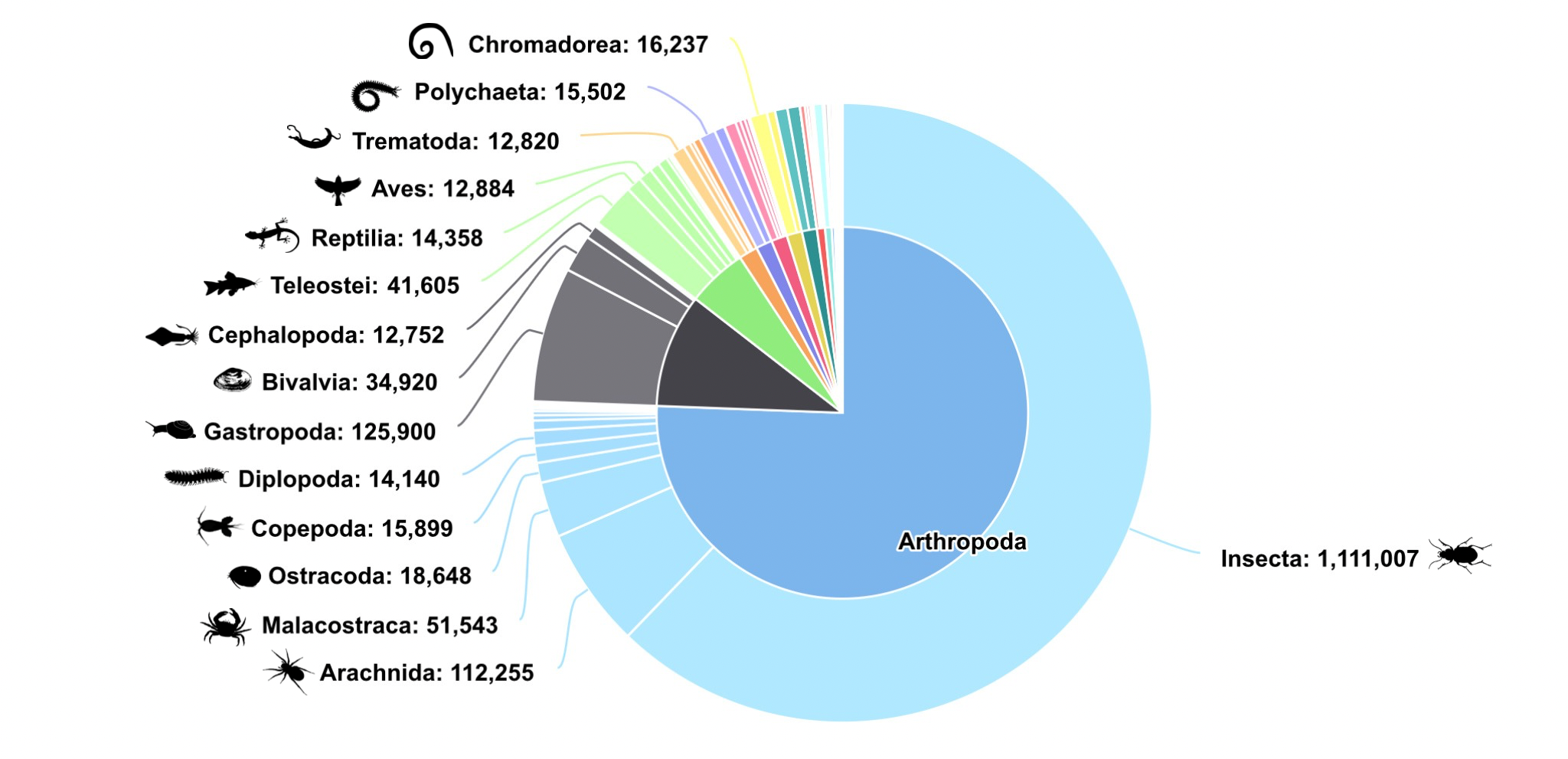

As of 2021, we've sequenced the genomes of nearly 3,300 animal species. That's 0.2% of the 1.6 million known species. How much knowledge of our past do we lose with the 150 species that go extinct every day, many of them still undescribed and unstudied? Each species lost is a book burned before it could even be read.⁶

Major classes of animals and their number of described species — many smaller classes (such as Mammalia, with 8,945 species) are unlabelled.

To put our utilitarian glasses on again for a moment, some of the knowledge we gain from our scientific investigation will be useful to us directly: unraveling the genetics behind the icefish’s antifreeze proteins can help improve preservation techniques for organs and food; insights from the naked mole-rat’s resistance to cancer and ability to survive low oxygen conditions could lead to breakthroughs in human medicine; and studying the immortal jellyfish, which can revert its cells to an earlier life stage and potentially escape death, may offer clues into cellular regeneration and the slowing of aging.

What about all the other knowledge we collect?

What will we do with all we've learned, recorded, and stashed in the great (now mostly digital) library of all human knowledge? Well, what might seem valueless today may come in useful to solve some future problem — maybe it takes several pieces of information, possibly discovered hundreds of years apart, and only combined do they spark an epiphany.

For some, collecting knowledge for the sake of knowledge itself is a worthy purpose. For others, it is a waste of resources and time that could be put to better use. We've long imagined a post-scarcity future in our sci-fi stories. Today, that future still seems a long way off. We live in a world where people have needs and where people hurt, in a world where many of those needs aren't being met and the pain goes unalleviated. In such a world, it's only natural to want to view things from a utilitarian perspective. Neither beauty, nor wonder, nor knowledge can feed a starving man or heal a sick one.

Anyone who scorns the utilitarian perspective as selfish or lesser-than is lucky enough to live a life where they can consider things beyond it.

Perhaps our species will reach that post-scarcity future. They might have everything they may need in their everyday lives. They may not suffer from hunger or disease. But neither will they know the beauty and wonder of a starling murmuration above a Roman skyline or throngs of firefly squid turning a bay blue in their last acts of lust and love. They'll never be able to discover the secrets of creatures that perished before they could even be known. What will spark their creativity, drive their discovery, inspire their art, give them meaning? The search for life elsewhere, that might not even exist?

They, our great-grandchildren many times over, might want to ask us why we left them with so little. If we could, how would we respond?

That we needed to uphold the economy?

That we were waiting for a miracle technology that never materialised?

That we prioritised artificial wealth over irreplaceable life?

Temporary comforts in exchange for lasting damage?

We might try to explain that the people who caused the vast majority of the damage had too much money and held too much power. That most people wanted the same thing — to live on a healthy planet and leave a better one for their children — but that some people refused to educate themselves or were purposefully misled by those in power. We might say the system we lived under was set up for endless growth, with no mind to the consequences.

In honesty, we might admit that, while half of the global population climbed the economic ladder to meet their basic needs — and, once met, continued the climb towards opulence — the already privileged weren't willing to give up their comforts and indulgences. The farms kept producing meat, the factories kept churning out disposable clothes, and the planes kept flying — because we wanted to eat steak, wear new fashion each month, and travel fast for cheap. It was not the individual, but the corporation that caused the harm. True enough. The corporations needed to change, but they saw no need to, because the individual continued to make them a profit.

In a way, the entire discussion — of saving biodiversity for future generations — is moot. If we ever want to reach a post-scarcity future, whether or not we actively decide to save the species we still have, we'd need to stop doing many of the things which cause their extinction, regardless.

Climate change destabilises weather, agriculture, and coastlines. It dries rivers, alters rainfall, and fuels fires that consume both forests and farms. A world of abundance couldn’t exist amid such volatility.

Forget about plenty of food for all; many will have to reckon with food scarcity as used-up soils erode, fisheries collapse, and pollinators vanish. It’s not just the wild ecosystems that starve. Humanity’s food supply draws from those same systems. Biodiversity loss translates to resource insecurity.

As habitats are destroyed, as wildlife is displaced or harvested, zoonotic diseases spill over into human populations — yet another symptom of ecological imbalance. We were only just recently reminded of the pandemic-causing consequences that such forced close-contact can have. Rather than post-scarcity, a post-apocalypse.

What if we don't succeed in overcoming these threats? What if they get so bad that, as unlikely as it may sound, our species goes extinct? What happens to all that's left of us?

If we don't find some way to safeguard our accumulated knowledge for some intelligent future species to find, it may well be lost. All that we've collected, passed down for tens of thousands of years, may be gone forever. All our art would eventually decay and fall apart, and our structures would crumble. The last remnants of our cultures, gone. What, then, would be our legacy? In this bleakest scenario for humankind, I propose that our one hope for some kind of continuation lies in taking a broader view. A view in which our legacy is not merely human.

Even if one day in the future, Homo sapiens fades to extinction, all of our brothers and sisters, our cousins (many times removed) — from sea angels to fireflies, flying frogs, bats, blue whales, and orangutans — could carry on the legacy of life on our planet Earth. Whatever the fate of humankind, I think it's better we strengthen that legacy, rather than impoverish it.

All the major and many of the minor living branches of life are shown on this diagram, but only a few of those that have gone extinct are shown.

(© 2008, 2017 Leonard Eisenberg, All rights reserved, evogeneao.com)

I want to end on a final note that's not to be diminished by its brevity. The subject could, and has, filled entire philosophy books. To some, it may be of little consequence. To others, it may decide the whole issue of extinction.

Animals — the rest of animal life — are more than their relationships to us: a single species out of 8 million or more. Animals aren't just here for us to use, they don't exist solely to be our muse, to inspire in us awe or spark understanding. They are living beings in their own right. We need not declare a doctrine of universal rights prescribed inherently to all living beings, for those are hard to come by unless you're a follower of some faith. But every human and every society, pious or atheistic, holds to a set of morals.

Of course, morality changes throughout time, differs across cultures, and isn't even consistent between individuals of the same culture. But I'd hazard a guess that a great majority of people today would agree that causing unnecessary suffering and death is an immoral thing to do. From an ethical perspective, the fact that animals are sentient — that they can experience pain and want to keep living — means that it’s not consistent with our already-held morals to cause their deaths or, ultimately, their extinction. Especially when the harm we cause is avoidable, and our survival does not depend on it. Of course, no one can live a life causing zero harm, but minimising that harm as much as possible is certainly a goal worth striving for.

Extinction isn't just a loss of species. It is a loss of potential, of beauty, of history, knowledge, and of ourselves. What legacy will we choose to leave behind? How will we choose to treat all the other beings who share our planet with us, who so greatly outnumber us, and yet are subject to our cruelty or kindness?

When humanity proclaimed control over the natural world, when we began to effect such great and terrible changes, we took up the role of guardian, of steward. If we can find purpose in the preservation and prosperity of our charge, no matter our own fate, we will live on forever in hummingbirds and vultures, in termites and electric fishes, fireflies and firefly squid, in butterflies and blue whales.

¹ Scientists have directly observed less than 0.001% of the Earth's deep seafloor.

² The likelihood of fossilisation varies depending on who you ask. Some scientists estimate that under 8-10% of animals are fossilised, while others argue that it’s as little as one-tenth of 1% (or 0.001%). The scarcity of fossils in general is compounded by another issue: the scarcity of specific types of fossils. The process of fossilisation favours certain structures over others. Hard parts like bones, teeth, and shells are far more likely to be preserved than soft tissues, feathers, or entire organisms with no mineralised structures at all. The environments that animals lived in also matter. Organisms that lived in sediment-rich aquatic settings had a better chance of fossilising than those in forests, mountains, or deserts, where remains were more likely to decay or be scavenged before being buried.

The fact that so few species have been fossilised only multiplies the number of extinct species that we don't know of, and can never know of. That massive roster might have contained some of the most awesome creatures that ever lived.

³ Vertebrates are defined by the presence of a backbone or spinal column and include mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. The notochord is a kind of precursor to a proper backbone and it still appears in vertebrate embryos during certain stages of development.

The presence of a notochord at some stage in life is not enough to classify an animal as a vertebrate, but it is enough for them to be considered a chordate — the phylum to which vertebrates belong. In creatures like lancelets, for instance, the notochord never develops into a proper backbone, so they are chordates but not vertebrates. Sea squirts, even though they look very much like cnidarians or sponges, are also considered chordates, since their swimming larval forms possess notochords, before they settle down into their sessile, blobby adult forms and lose them.

⁴ When studying modern species for insights into the past, it's important to remember that organisms aren't static; that they've continued evolving. Modern lungfish aren't the same fish that first crawled onto land, the salamanders and frogs today aren't the same as the first amphibians, and nor are present-day reptiles replicas of their ancient ancestors.

The terms ancient or primitive are sometimes used to refer to older lineages of animals, but they can be misleading. While some groups arose earlier than others, at no point did they stop changing; they didn't reach some point where evolution was put on pause. Fish didn't stop evolving when amphibians emerged. And while amphibians as a group may have arisen before mammals, the amphibians living today are as modern as today's mammals.

Living species will differ in some traits from their ancestors. Other traits they'll have retained throughout the millions of years. It is these latter traits which we examine when we look to modern species as analogous to those now extinct. We must be cautious when trying to glimpse the past in this way. The insights, however, are worth the effort.

⁵ Despite the existence of forest and savannah-dwelling populations, the African elephant was once thought a single species. However, an analysis comparing the nuclear DNA of several proboscideans (the elephant order) — both alive and extinct — found that the African forest elephant and African bush elephant likely diverged genetically at least 1.9 million years ago, and now they’re considered two distinct species. A similar thing happened with the giraffe, which was split into four species after genetic studies found that they had not exchanged information between one another for one to two million years.

The opposite happened to the Iriomote cat. Found on the Japanese island of Iriomote, this feline was initially proposed as its own species (Mayailurus iriomotensis) due to some of its primitive morphological features. Then it was classified as a subspecies of the widespread mainland leopard (Prionailurus bengalensis iriomotensis). And later, after an analysis of its genome was found to be nearly identical to the leopard cat, even its subspecies status was called into question.

The island of Iriomote was connected to the mainland via Taiwan during the Ice Ages. Mainland and island cats are thought to have crossed the landbridge and mixed their genopools as recently as 20,000 to 240,000 years ago. But you wouldn’t know it just by looking at them, a mainland leopard cat and an Iriomote cat, for they truly do look quite distinct.

⁶ And it's important to remember that a genome isn't everything — isn't even the majority — of the information making up a species. There's so much we can't extract about a species just from reading its DNA. At least not yet, and maybe not ever, given how increasingly complicated we're discovering the pathway from nucleotide sequence to phenotypic effect to be.

That's to say, even those species whose genomes we've sequenced, if we lost them without learning any more about them, we can not say we ever really knew them.

-

Ecological

Nature’s Technicians — seed dispersers

Cornell Chronicle — snakes as seed dispersers

Animal Diversity Web — dwarf cassowary

UC Santa Cruz — sea otters and urchins

Earth Justice — wolves in Yellowstone

New Zealand Birds Online — Haast’s eagle

Cell: Current Biology — fig wasps and figs

Utilitarian

Ask Nature — kingfisher beak as inspiration for bullet train

World Economic Forum — pollinators and crops

Nature’s Technicians — pollinators

Crop pollination services by Lonsdorf, et al.

European Commission — pollinators

New calculations indicate that 90% of flowering plant species are animal-pollinated by Tong, et al.

Bat Conservation International — bats as pollinators

Bat Conservation International — bats and agave

National Park Service — chocolate midge

The Institute for Climate and Sustainable Growth — Four Pests Campaign in China (eradication of sparrows)

The Economist — Four Pests Campaign in China (eradication of sparrows)

BBC — Indian vulture crisis

Mongabay — gecko adhesion biomimicry

Smithsonian’s Ocean — shark scales sterility biomimicry

World Economic Forum — termite mound ventilation biomimicry

Smithsonian’s Ocean — deep-sea fish ultra black biomimicry

Electric eels by Kenneth C. Catania

The Conservation — electric eels and the invention of the battery

Cultural

National Park Service — people and the bison

South Dakota State University — bison genocide

Buffalo Bill Center of the West — bison and plains people

BirdLife DataZone — resplendent quetzal and Aztecs and Mayans

Mongabay — snow leopard in Buddhism

Scientific American — alala or Hawaiian crow

Hawaii.gov — alala in Hawaiian culture

National Geographic— Arabian “unicorn”

BirdLife DataZone — red-crowned crane

Brazil, M. (2022). Japan: The natural history of an asian archipelago. Princeton University Press.

National Museum of the American Indian — the “salmon people”

CRITFC — tribal salmon culture

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service — salmon in the Pacific Northwest

New Zealand Herpetological Society — jewelled gecko

Mongabay — superb lyrebird’s song

Cambridge Butterfly Conservatory — butterfly diversity

Wonder

National Audubon Society — Arctic tern migration

National Audubon Society — bar-headed geese migration

The Peregrine Fund — Rüppell's vulture altitude

BBC Science Focus — leaf-cutter ant fungus gardens

Cell: Current Biology — aphid-farming ants

PBS NOVA — magnetic termites

Saola Working Group — saola or “Asian unicorn”

GBIF — hooded pitohui

BBC Discover Wildlife — coconut octopus

Natural History Museum — blue-ringed octopus

National Geographic — mimic octopus

What Is It Like to Be a Bat? by Thomas Nagel

Science — pigeons sense magnetic fields

Science — knifefish electroreceptiom

National Wildlife Federation — how birds see the world

Ultraviolet signals in birds are special. by Haussmann, et al.

MBARI — Pompeii worm

BBC Discover Wildlife — giant siphonophore

Scientific

University of Saint Andrew’s — lancelets and evolution of vertebrates

Lung evolution in vertebrates and the water-to-land transition by Cupello, et al.

The evolution of phototransduction and eyes by Lamb, et al.

Natural History Museum — convergent evolution

Eberly College of Science — whales and hippos

The origin of animals and fungi by Linda Koch

Natural History Museum — birds are dinosaurs

Toward a genome sequence for every animal: Where are we now? by Hotaling, et al.

BBC — biodiversity loss

Fish antifreeze protein and the freezing and recrystallization of ice by Knight, et al.

Use of tumor suppressor genes of naked mole rats for human cancer treatment by Xia & Xu

Zoonotic diseases: understanding the risks and mitigating the threats by Elsohaby and Villa

UN Environment Programme — climate change future

NASA — effects of climate change

Mongabay — seafloor observed

Footnotes

BBC — fossilisation

University of California Museum of Paleontology — fossilisation

University of California Museum of Paleontology — chordates

University of Hawai’i at Mānoa — chordates

Encyclopaedia Britannica — sea squirts

Natural History Museum — elephant taxonomy

Giraffe Conservation Foundation — giraffe taxonomy

Ball, P. (2025). How life works: A user’s guide to the new biology. Tantor Media.

-

Attribution under each photo (click dot in bottom right corner).